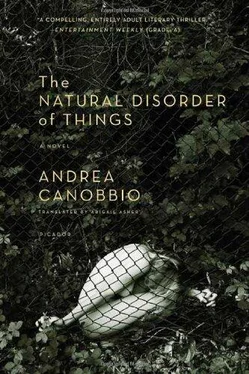

Andrea Canobbio - The Natural Disorder of Things

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrea Canobbio - The Natural Disorder of Things» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2007, Издательство: Picador, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Natural Disorder of Things

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Natural Disorder of Things: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Natural Disorder of Things»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Natural Disorder of Things — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Natural Disorder of Things», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I parked too. I walked past the dark wood door, slowing down and examining the panel of buzzers long enough to see “Renal” amid a crowd of strangers’ names: Renal, third floor on the right. I didn’t know what to do, what a professional detective would have done in this case; maybe he’d have waited all day — but his business would have been tailing people, not designing gardens. In any case, I needed to call some suppliers, and the bar across the avenue didn’t look too smoky. I sat down at a table by the window and ordered a cappuccino and two croissants. I made my calls while running my eyes over the imposing 1920s building: some windows were plain, but others were French doors opening onto balconies; bow windows ran up each corner of the building; and in the hierarchy of the apartments, the best ones were clearly on the lower floors. I stared so long at the façade that suddenly it seemed to move, to expand and stretch and swell as if something were pushing to get out, like an enormous sigh that would shatter the window glass and scatter transparent debris along the avenue.

After an hour I got bored: the building didn’t get a lot of visitors; in fact, no one had gone in or out, and wasting a day like this didn’t seem childish anymore — it seemed just moronic. I paid and abandoned my post. As I crossed the avenue, I noticed that the sky was clearing, and I pictured the woods and the pond and the slope of the meadow, and Witold and the others at work, and the details of the project, the little mistakes that were surely piling up in my absence. When I got to the car, I picked a flyer off my windshield, and it suddenly hit me that Elisabetta Renal could have come out during my brief stop in the bar’s bathroom. The flyer promised “Easy Financing! — Full-time employees: get a cash advance on your paycheck — Small-business owners: moneyorder financing available—5 million lire in 120 payments of 69,000 lire each, at only 6.5 %—Only one signature needed (even for married applicants) — Don’t worry if you have a poor credit rating or outstanding liens — No matter what other loans you already have — Even if you already have a paycheck advance — Let us come to your home and tell you how.” A wastepaper basket stood at the corner, a few yards beyond the building’s entrance.

I went past the buzzers, and on a sudden impulse I pressed a buzzer at the top left. A man’s voice answered, said “Who is it?” a few times, but he didn’t open the door. I pressed another buzzer, a few buttons down, and the people buzzed me in without saying a word. The dark lobby opened onto a narrow courtyard lined with green climbers that absorbed all the light. The stairs were made of black stone, the railing of hammered iron. I went up to the third floor, but the plaque on the door was as vague as the buzzer: RENAL. Before I could turn and go back downstairs, one side of the double doors opened up.

An old woman appeared: metallic blue hair, camel coat with enormous buttons. She had keys in her hand: she was going out. I stepped back into the shadows on the landing and stood silently. The woman studied me without interest, waiting for me to speak. I hesitated five seconds, and then I held out the flyer I had in my pocket. Suddenly she sprang to life. “No, no — there’s a big sign downstairs, didn’t you see it? No flyers allowed in this building.” And she shook her withered finger in my face, taking me for a deaf-mute. I nodded and shrugged and even produced a disappointed whimper. Then from inside the apartment I heard Elisabetta’s voice, very nearby, saying, “Did you take the letters to be mailed?” The woman turned around. I was paralyzed. “Did he offend you?” Elisabetta continued. “No,” the woman answered, “I know him pretty well by now.”

At this point I managed to tear myself away from the landing and flee down the stairs. Out in the street, I hugged the wall to keep from being seen, just in case Elisabetta Renal came to the window. When I reached the corner, I turned left so I could get to my car by going all the way around the block, and that was when I discovered the clothing shop, the same shop I would go back to a few days later; I studied the display windows, trying to act nonchalant, pretending that I’d just been passing by, but I hadn’t yet decided to redo my wardrobe; no, I was actually thinking of Fabio.

It’s incredible that it took so many hours for Fabio to come to mind: Elisabetta Renal and Conti were not the only two people I’d tailed in my life, and that other time, too, someone had asked me to do it, and that other time, too, I had refused at first but then secretly obeyed. “Go and see where he goes,” my mother had said to me. I couldn’t do that — it wasn’t right. I had turned her down. And then I followed him. I didn’t tell my mother where he went — she already knew anyway, we all knew … what was there to discover? But of course my mother was actually asking for something else. She said “Go and see where he goes,” but clearly she meant “Do something, save him”—how absurd that she asked it of me: I didn’t even know how to save my dog from his insane passion for the woods, and now he was gone. Why me? Why not Carlo? Just because Carlo was far away, studying in another city? Or to avoid distracting him, because it was important not to worry him? So it fell to me: “Go and see where he goes.” As if nothing bad could happen to him as long as I was following him. But it seemed that the opposite was true: when I followed people, I hurried them toward their deaths.

I watched the movements of the bald salesman through the reflections on the glass. No wonder I’d felt so good, no wonder I’d thought of the word “peaceful” that morning when I began following Elisabetta. It was because I was going back to what I did in the old days, and it never matters whether the old days were good or bad. “And yet remembering gladdens you, as does the fresh return of the time of your unhappiness” (Witold Witkiewicz).

I got the first phone call from my brother after that trip to the city, and on the following nights I couldn’t stand being home when it got late — I needed to do something. Elisabetta Renal was still ignoring me, as if nothing had happened, and I was gripped by an urge to find out everything about her life. Each night I would stand guard in front of the abandoned factory, which seemed more and more — especially in the dark — like the giant skull of a beast that had been dead for millions of years, thrust into view now by the erosion of the land around it. Regularly at around eleven (“in the middle of the night,” as Rossi had said), the Ka would appear at the fork and turn left. For a few nights she drove around without stopping, as Rossi had said, and her meandering seemed to trace a series of spirals around the villa, as if she were trying to say that she wanted to get away, or that getting away was impossible.

One night she stopped in front of a club that has had three different names over the past three years: Blue Nightclub, The Flower Piano Bar, and Blue Dahlia — A Members-Only Club. The name was written with a complicated twist of blue neon tubing molded into softly looping script. She waited until a metallic gray Audi A8 drove up and two men got out. She went into the club with them. I had brought along a thermos full of coffee, and I immediately poured myself a cup, turned on the interior light, and began reading the newspaper I’d bought that morning with the idea of whiling away the time during my long wait.

I was parked in front of the window of a furniture store, reading about hails of bombs, rivers of fire, ten thousand refugees, ethnic cleansing, and atrocities; about age-old vendettas, innocent women and children, outdated maps, and Chinese embassies targeted by mistake. Every now and then I looked up at the living room displayed behind the plate-glass window: a sofa and two armchairs upholstered in zebra-striped Ultrasuede, a colonial-style rattan chaise longue, a fake kilim rug, twin towers of metal for storing CDs and videos; the TV was on and running the late news, the glass-fronted bookcase was bare, the shelves enlivened by vases of fake flowers; there was no one in the living room, naturally, but the couple of times that I raised my eyes to look, the emptiness seemed absurd and incongruous. I thought maybe they could have found someone willing to spend the night in that living room. I imagined myself sitting there comfortably, nestled in an armchair, chatting with another stand-in; but I would have preferred the sofa to be tiger-striped, to please the kids (Carlo could bring them to visit me there).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Natural Disorder of Things»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Natural Disorder of Things» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Natural Disorder of Things» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.