I have no clear memory of how long I lay in this position, only that after a period the noise and the smell abated somewhat. I opened my eyes, got to my knees and saw Arthur standing in the light of a fire that was glowing once more with a reassuring orange flame, exclaiming, excitedly, “Bats. Dear God in Heaven. Bats.”

We walked over and saw, strung between his hands, a furry body the size of a field mouse at the junction of two segmented, translucent wings. “Some near-cousin of Tadarida brasiliensis ,” he said, “plucked from the air by my own hands.” The struggling animal possessed the face of one of the demons in the illustrated Bible which had given my younger brother nightmares when we were children. “There was, after all, some point to those tedious afternoons at deep square leg.”

“ Arthura brasiliensis ,” said Bill. “You’ll go down in history.”

“ Tadarida arthuriensis ,” replied Arthur. He broke the neck of the creature with a sharp twist and dropped it into his pocket. “ Brasiliensis is the adjective. And you may call me greedy but I’d prefer a more substantial memorial.”

“A bat would suit me just fine,” said Bill. “A flower, a tree…”

I returned to my bed, lay down and watched the Via Galactica reveal itself, the sky so clear and dark that I was able to discern the colours of individual stars, each one burning with the light of a different spectrum according to the peculiar combination of elements which fuelled its monstrous furnace. I fell finally into a doze and was woken, as was everyone else, by the return of the bats just before dawn.

While we were eating breakfast I rolled up my trousers and discovered a raised purple lump on my left calf. The cotton duck of my trousers had not been punctured so it must have been the bite of some creature, perhaps one of the brown spiders through whose webs we had been walking repeatedly over the last couple of days. I showed the lesion to Arthur, the only one of us with any medical knowledge now that Nicholas was gone. He advised me to wait and see if the swelling and discoloration went down before risking any further intervention.

He and Edgar then prepared themselves for their journey underground, donning all their clothes against the cold and equipping themselves with the remaining rope, two belay devices, the two handguns, a machete, water, food and both our oil lamps.

“We shall press ahead for two hours at most,” said Edgar. “Then we will return. If after four hours we have not reappeared you must decide whether to search for us or attempt the journey home alone.” There was relish in his voice as if he might enjoy playing any of the roles in such a scenario.

We wished the two men luck, bid them goodbye, gathered the spade and the machetes and made our way to the cross which Bill and Arthur had discovered the previous day so that we might dig for bodies and find some clues as to the fate of our predecessors. I was very grateful indeed not to be entering the cave. I was convinced that something would go wrong and the fact that my sense of impending doom was without foundation made it no easier to bear. If Bill and I were lucky enough to uncover Carlysle’s body, however, and identify it by means of his signet ring, for example, we might soon be heading home.

I was unnaturally tired and after half an hour of labour Bill suggested that I sit to one side and resume the work when I felt stronger. By this time we had uncovered two graves. Bill put down his machete, picked up the antique spade and began to excavate the second of these. Within a very short time he struck a human femur. Digging more carefully now he rapidly produced a skull complete with a jawbone and a nearly complete set of teeth. Sinews and muscle were stretched around the whole like ageing strings of India rubber. He brushed the earth away and handed it to me. It seemed fake, a theatrical prop or a desktop memento mori.

I remained incapable of significant manual labour. Bill said that there was no hurry and that my exhausting myself would be to no one’s advantage. Within half an hour I was handed a second skull, this one incomplete, the dome shattered and absent on the left-hand side of the head. These dead men were the reason we had made this laborious and fatal journey yet I could summon little interest. Bill returned after a few minutes carrying a handful of broken fragments. He laid them out like a jigsaw and fitted them together, the final shape mirroring the hole in the skull I still held in my hand. “He was killed by a heavy blow to the head.”

I asked Bill how he could be certain of this.

“If a man were to fall from a cliff he would crack his skull at most. To do this you would need to hold him down and stave his head in with a rock.”

“Then he was killed by one of his own party.”

“Or someone was already here and did not want company.”

“And it was they, perhaps, who buried the bodies and spirited away the expedition’s equipment.”

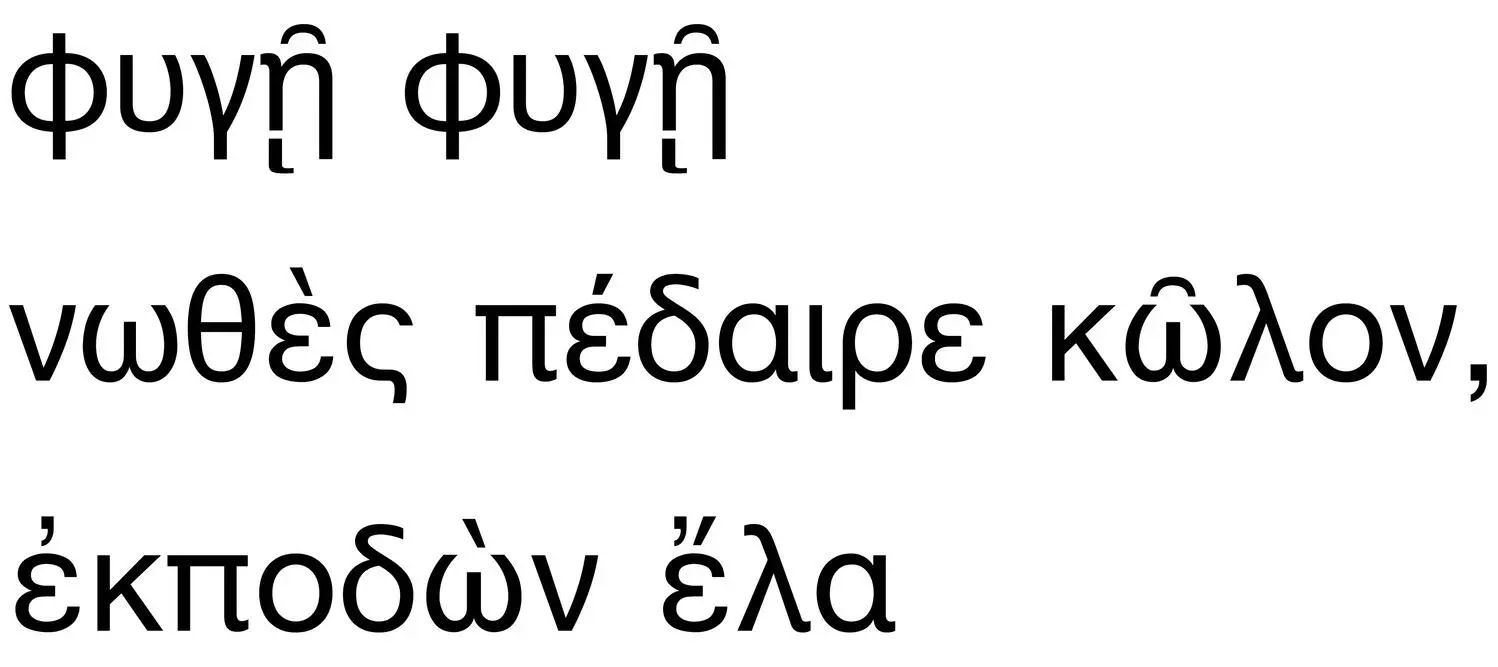

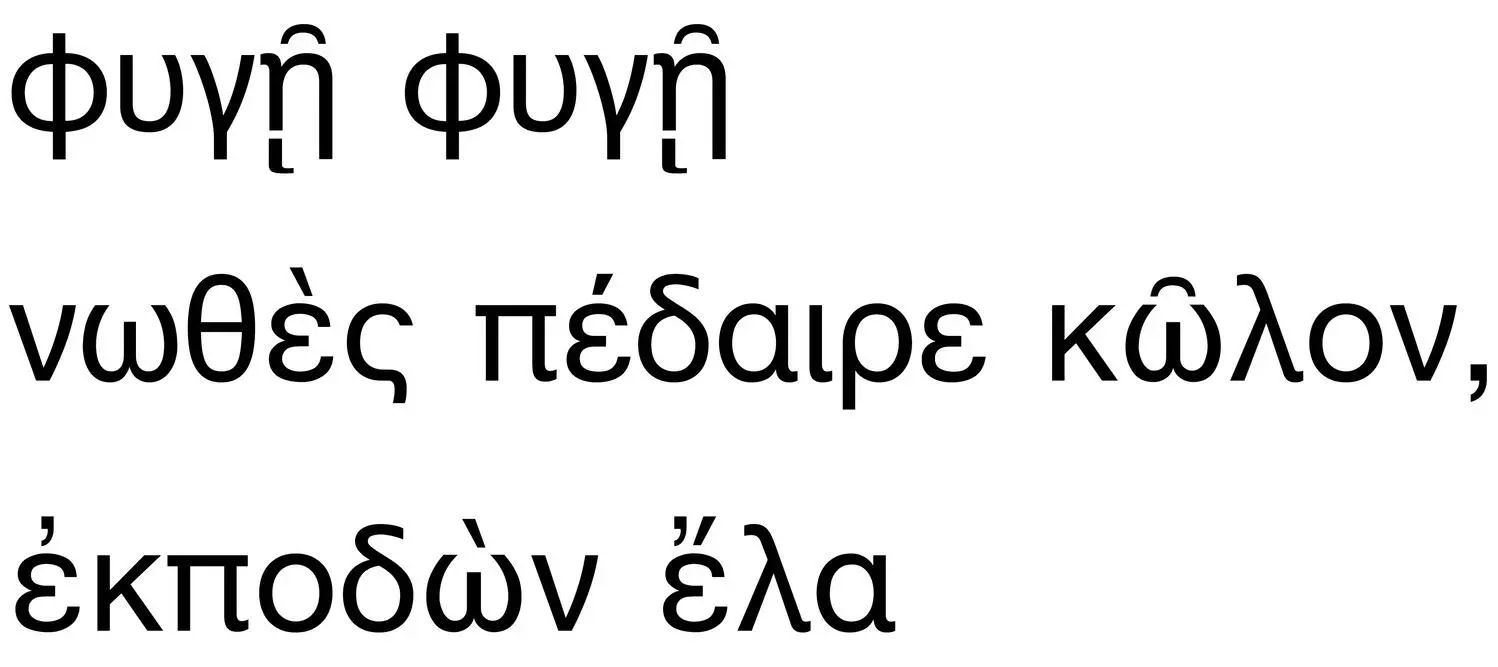

Something had caught Bill’s eye. He picked up one of the machetes and began cutting back a mass of vines and creepers which had climbed the side of the rock before petering out for lack of damp soil. He pulled back the foliage and I could see letters scratched into the rock. I got slowly to my feet and walked over so that I could read the inscription.

“I assume you can tell me what it means,” said Bill.

I confessed that my Greek was poor but that the word repeated in the first line almost certainly meant “flee,” from the same root as “fugue” and “fugitive.” As for the meaning of the second and third lines I had little or no idea.

Bill looked at the sun. “Four hours have passed.”

I had become so preoccupied by the graves, the skulls and the inscription that I had forgotten about Edgar and Arthur. We made our way back up onto the top of the rock, Bill striding comfortably ahead, the muscles in my legs protesting at the incline. Our little camp was empty and the two men were nowhere to be seen. My premonition had been correct.

“So,” said Bill. “We have a decision to make.”

It had not occurred to me that Bill might take Edgar’s instructions literally. For a moment I was tempted. Then my senses returned. “There is no decision to make.”

We dressed as warmly as possible. There were no more lamps so I lit a fire while Bill hammered and split the ends of two staves of firewood to make brands. We took up a machete each, oiled and lit the brands then entered the cave.

The walls, illuminated now, were rippled and bulbous as if formed from a substance which had hardened suddenly in its melting. I had expected irregularities — overhangs, narrows, drops, forks, subsidiary chambers — but there were none. There were patches of moss but otherwise surprisingly little vegetation for so fecund an atmosphere. The temperature dropped swiftly to that of a cold January day in England. We passed the point beyond which we were able to see the entrance to the cave and shortly thereafter we could no longer see the roof above our heads. I guessed that the cave must have been at least five hundred feet high at this point.

The previous year I had listened to a speech at the Royal Geographical Society given by Alois Ulrich who had been exploring the Hölloch in the Swiss municipality of Muotathal which appeared to be at least ten miles in extent. I wondered if we had stumbled upon something commensurate. There were no longer any echoes as such, only a sibilant background to every noise, like a stiff brush dragged across a drum skin. Every so often we stopped and called out, standing in silence afterwards, letting the reverberations die slowly to silence and listening for any answering cries, but none came.

Читать дальше