“Now say the frog wants to hop to the pond,” said Mr. Lawrence, and already I was remembering the image of my father, Rotpeter, raping the throat of an even less fortunate frog than this one. I shook off the unpleasant memory and tried to pay attention.

“But! — there’s a problem: each time he takes another hop, the frog can only hop half the distance of the last hop.”

What? — I thought, my mind beginning to roil — why? — what kind of bizarre hopping disorder afflicts this particular frog?

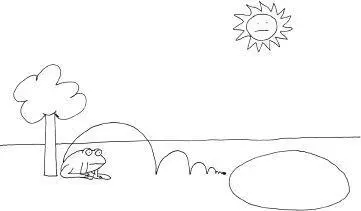

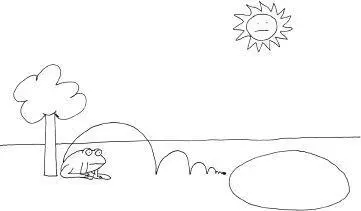

“So right away he hops halfway to the pond,” and with a sweeping squeak of the black marker Mr. Lawrence drew a parabola that spanned from the frog, seated at the base of the tree, to a point about halfway across the plane between tree and pond, representing the arcing motion of the frog’s first hop.

“Then, on the second hop, the frog only hops half of the distance he just hopped.” Mr. Lawrence drew another arc, about half as big as the last one. “On the third hop, he can only hop half the distance of that hop, and then half of that and half of that…” Mr. Lawrence’s voice grew quieter and quieter as the hops he was drawing dribbled into a squiggle that culminated in a static black blot representing the point at which the exponentially diminishing distances of the frog’s hops had become unillustratably microscopic. Like this:

I glanced over at Clever, sitting in the schoolboy’s desk beside me. Ours were the only two desks in the classroom. Clever was scratching the back of his neck and looking out the window.

“So then,” said Mr. Lawrence, turning to face us. Clever dragged his gaze from the window to the whiteboard in a pretense of attention. “ When will the frog reach the pond?”

I reasoned that although he was moving very slowly, the frog was in fact moving forward, so surely he had to get there at some point unless he died of thirst before reaching the pond, which at the rate he was going had to be a concern.

“Nope!” said Mr. Lawrence, with a certain pedantic pleasure evident in his bright eyes and lips pursed beneath the snowy broom of his mustache.

“Clever?”

Clever shrugged his shoulders, more from apathy than ignorance.

“Because space is infinitely divisible,” Mr. Lawrence concluded in triumph, “the frog will never reach the pond! ”

But how could this be possible? I thought. As I remember, I pointed out that the frog himself must take up a certain amount of space, and I asked how it was that the frog could leap a distance shorter than the length of his own body. I looked at the illustration, eyeballed the size of the frog drawn beneath the tree and visually measured it against the amount of space that remained between the edge of the pond and the black blot at the end of the frog’s trajectory where the hops had grown too tiny to see, and it looked to me that the yet-untraveled distance was shorter than the frog himself, so surely he was close enough to the pond that he could simply bend his lips to the edge of the water to drink. I remember asking this, and I remember Mr. Lawrence’s response was twofold: (one) that he never said the frog wanted to go to the pond because he wanted to drink, only that he wanted to go there because he wanted to be at the pond (to swim, then? I wondered); and (two) that I was for the purposes of the thought experiment to ignore the body of the frog , that this was an abstract, mathematical frog, a frog who is merely a point in space devoid of volume, area, or any other dimensional analog. I could not even begin to fathom how a frog could be a volumeless point in space and still be considered a frog. And then I began to ponder the fate of this poor frog, who was doomed by his rare and improbable condition to die en route to his destination, so very close to it, within sight, within mere inches of the pond, yet effectively stuck there, out of reach of it. Much later, I would read the Greek myths about the cruel and ironical tortures that certain heroes had to endure for eternity in Hades: about Prometheus, shackled to a rock, whose liver regenerates in his body every night so that come the morning the eagle may disembowel him afresh; or Sisyphus, who must in endless repetition roll his rock uphill until he’s moments away from finishing the job, when he loses his grip on it and must watch it tumble back to the foot of the mountain; or Tantalus, forced to stand forever in a pool within arm’s reach of branches burdened fat with fruit, but doomed to everlasting hunger and thirst because the branches of the tree bend just out of reach when he tries to pick the fruit, and the water at his feet evaporates if he kneels to drink it; and studying these mythological punishments I recalled the unfinishable journey of Xeno’s incorporeal frog, and wondered what it was about the psychology of this famous race of wisdom-loving ancients that made them so fascinated and horrified by the eternal wax-and-wane of favor and denial, of futile labors and frustrated desires.

After class was dismissed, Clever and I would be released to play outside. We would skip through the fields of grass with Sukie the dog, and play fetch, or go for long walks in the woods, or go to pet or feed the animals with Lydia.

When I had begun to speak articulately enough that people other than Lydia could understand me, Lydia extracted a promise from me: that for the time being, I would not speak to any humans who did not already know my secret. If I was in the presence of her, or the other chimps, or Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence, or Rita — all the people in the world who knew I could talk — then I could say all I liked, but around anyone else mum was the word. The reason for this moratorium on my speaking was that she wanted to keep me a secret from the world in order to give her as much time as possible to teach and study me in peace and without the winds of unwanted publicity and public outcry howling at the door. I complied with her request of my silence. I slipped up only once.

Clever and I would often take walks along the high metal fence that separated the vineyards from the free-range area of Mr. Lawrence’s property. It looked much like the tall chain-link fence that surrounds the research center where I live now. Clever and I enjoyed conversations together, of a certain sort. Linguistically speaking, they were all very one-sided. I did all the talking, and he just made gestures that I failed to understand. I liked his company though, and he liked mine: we were friends. We were walking along the fence, with Sukie, the dog, yapping and panting about ten feet up ahead of us. Clever and I walked side by side. My hands were clasped behind my back, and I was in the middle of pontificating aloud on some ponderous philosophical subject, while Clever mutely listened, dragging a stick against the fence to make it go clink-clink-clink-clink as we walked.

“… and indeed,” I was saying to Clever, “not even Augustine conceived of a God in terms of material imagination, yet for Kierkegaard—” I stopped cold, my thought truncated in midsentence. I had been so lost in my soliloquizing that I was startled by a small grubby-faced child standing just on the other side of the fence, looking out at us. Her star-kissed ink-black eyes were transfixed in an expression halfway between wonder and fear. She stood stock-still, silent. She had heard every word.

I looked past her. Up ahead, in the vineyard, in the aisle of dirt between two long fences covered in grape vines, was a group of vineyard workers. They were bent over their labor: picking the grapes and putting them in the big plastic buckets that hung from their fingers. They wore straw hats to keep off the October sun that glued their clothes to their skin with sweat. Some of them were barefoot; some of the men were shirtless. The little girl who had heard me speak ran off toward them. Clever and I stood there at the fence, trading nervous looks, unsure of what to do.

Читать дальше