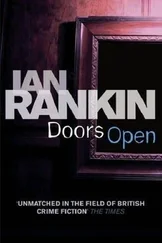

Iosi Havilio - Open Door

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iosi Havilio - Open Door» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: And Other Stories, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Open Door

- Автор:

- Издательство:And Other Stories

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Open Door: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Open Door»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Iosi Havilio

Open Door

Open Door — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Open Door», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

That evening, he heated up some stew, a bit dry, but tasty. During the meal he asked me if I would mind sleeping in his bed with him. He said it would be more comfortable for both of us. The armchair, he explained, is too rickety. I smiled.

When we entered the bedroom, full of faded pictures and oversized furniture, the ceiling high above our heads, I sat on the edge of the bed waiting for Jaime to throw himself on top of me. He didn’t. He touched me a bit, out of a sense of duty. That was it.

I wake in the middle of the night and discover a bronze crucifix hanging on the wall, which prompts a long shudder. How come I didn’t see it before? I sit up in bed, Jaime is at my side, on his back, his teeth and gums on show. I have the urge to run my finger around his lips. And close his mouth. I’m thirsty. I don’t dare to leave the room, this much silence scares me. I wrap myself tightly in the blanket which has fallen on the floor and I drop off again without too much trouble.

Morning brought a ferocious headache. Jaime heard me moaning, he tells me as he tips up the kettle and a torrent of steaming water cascades into the mouth of the maté gourd. It’s a bright and shining morning.

‘Were you dreaming?’

‘Yes,’ I say to reassure him.

Jaime passes me the maté. I feel good by his side. I ask after the other Jaime, whether he’s already been to see him, he says yes, he seems a bit better, livelier, he even saw him eating enthusiastically. That made me happy and I even thought that perhaps the horse would survive a few days longer than expected.

‘And you, did you dream?’ I asked Jaime.

‘No, not last night. But sometimes I do.’

‘About what?’

‘About anything, nothing really.’

‘And what’s it like?’

‘Always the same.’

Jaime wasn’t being honest, he was looking to one side, hiding something. Something in his ‘nothing really’. Later, he left me alone in the house for an hour. I lolled in a canvas deckchair I found folded against the veranda wall. I stayed motionless the entire time, slack, forgetting about my body. The headache dissolved in the humid, mid-morning calm. Through the soft aura of the sunlight I could see the gate through which the truck had driven off, the row of poplars bordering the road, behind which a team of polo players was training, the sown fields, and farther away, in the distance, a long, low hovel, unfinished and badly made, with a corrugated iron roof and an electric-blue water tank connected by an orangey pipe to the back of the house, and infinite lamp posts, and all those wire fences before the horizon. The countryside, that was it: a jigsaw whose pieces could join together differently every time you blinked.

Jaime returned with a bundle of wood, a bag holding meat, lettuce, a pile of potatoes and sweet potatoes and some tomatoes. With him was a short man, with a flat face and almost no neck, the kind of guy who seems to have been formed in a mould. He took charge of preparing the barbecue, without speaking, or even looking much. A man whom Jaime called Boca.

‘I have to go back this evening,’ I said to Jaime after we’d eaten. He had his back to me, but I could sense his reproach. ‘I have to work early tomorrow,’ I explained, ‘I’m expected at the surgery.’

Again he protested, silently, without getting angry. With one hand, his left, he grabbed a bottle of wine by the neck and filled a glass in front of his chest, which he offered to me with the other hand, without turning round. I waited. I wanted him to look me in the eye. How many seconds, or minutes, can he stay like this, I wondered, like last night, lying in bed, his gaze focused somewhere far away from me, his bloated hand, so rough, squeezing my tits, perhaps, it occurred to me now, because he preferred not to see them. I’d helped him to undress me, he’d hurried me on, he’d pulled off my knickers with one tug, and there I was, for the taking. He stared out of the corner of his eye at the tufts of curly hair covering my sex, and I directed one of his hands down there, he let me do it, but he didn’t touch me, or stroke me, or rub me, he let his hand drop, like someone covering a hole so that nothing gets in or out. There he was, immobile, for a long time, and I didn’t dare to take his clothes off as I had planned. I was falling into a deep sleep and he had to cover me with the blanket and switch off the bedside lamp.

Just like yesterday, Jaime didn’t move. I took the charged glass, lingering for an instant with my fingertips brushing his rough hands, wide and paw-like.

The short man Jaime had brought to do the barbecue and who’d sat down to eat with us without a word was stretched out in the shade a few metres away. He was snoozing, belly-up, his forehead marked with charcoal.

I go back by train. Jaime drops me at the Luján bus station. I soon find out that an unexpected transport strike has just been called, that the last bus left at six thirty and that service is suspended until further notice. An improvised handwritten sign is repeated in various ticket windows: ‘ No service ’. A man tells me that if it were up to him he’d make the trip but the thing is that on the motorway they might pelt the bus with rocks. Or shoot at it, adds another man with his back to us, playing solitaire on a computer. The next train leaves in twenty minutes, says a voice from within. It’s raining. I approach the taxi rank and take the first of a long queue, which gets me to the railway station in under five minutes. The platform is filling with people, most of them students, calming their nerves with cigarettes and increasingly rowdy conversations. There are also workers, pensioners, women with babies and a pair of drunks resting their elbows on a hamburger stand. The train finally arrives, ten minutes late. It’s empty and I sit down by a window that won’t shut. I swap seats, but soon, when the train starts moving, the window catch gives way and I have to hold it all through the journey to keep from getting wet. In the next compartment, across the corridor, are four young seminary students, each one younger than the next. Only one of them is dressed as a priest. But there’s no doubt, it’s patently obvious that they are a brotherhood. They chat, read and joke amongst themselves. The one in the cassock has a guitar case between his legs. The carriage fills up, the atmosphere becomes tense. The jolting of the train begins to lull me to sleep, until an unexpected event draws my attention. It’s not entirely clear how or when the fight begins. First there’s a struggle that the darkness doesn’t let me see fully. There are three or four involved, boys and girls, pulling at each other’s hair on the platform of a very old station, while the doors of the train are still open. There’s a bicycle in the middle, someone slips, someone else clings onto a wheel, kicking in the air. It’s no big deal, it’s not serious, and yet it’s enough to change the course of the journey. The boy on the ground manages to crawl onto the train, dragging the handlebars behind him. The student priests fall silent, they observe the situation, they question it with their eyes, slightly tense, but they don’t intervene. The doors close suddenly and the boy who made it on board gradually composes himself. Those left on the platform kick the chassis of the carriage and one of the boys, or girls, launches a gob of spit that splats against the student priests’ window.

Initially, it’s hard to tell whether the boy who got on the train is the victim or the culprit. His face is flushed, he trembles slightly, and, despite being a robust lad, he looks ready to spill a few tears at any moment. There’s no doubt that he’s the victim. With his gaze glued to the window, mortified, he hides as best he can from the stares of those around him, he rubs his mud-soiled hands, and discovers a small superficial wound on his right palm, which he spends the rest of the journey sucking. Occasionally, he bites his right thumb as well, whether to control the pain or because he’s angry, I don’t know. He wants time to pass more quickly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Open Door»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Open Door» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Open Door» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.