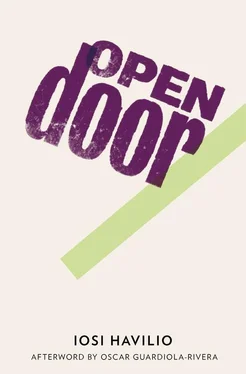

Iosi Havilio - Open Door

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iosi Havilio - Open Door» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: And Other Stories, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Open Door

- Автор:

- Издательство:And Other Stories

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Open Door: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Open Door»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Iosi Havilio

Open Door

Open Door — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Open Door», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Now the woman with glasses is leaning against one of the columns, rocking a baby in a nappy. The others are still there, sprawled on the chairs, drinks in hand, touching one another’s feet. Erotic games. And, not really knowing how long I’ve been holding this rifle with a silencer and laser sight, I point it at the baby, resting the flickering, red circle on its forehead. No one protests, it’s all normal. I change target, from the baby to the man with hardly any hair, and I start swivelling round, marking all of them with the glowing ring, one by one: heads, legs, shoulders, pelvises, at random. It’s insane, but it seems as though I’m going to kill them all.

Boca and Jaime are always playing truco , they never tire of it. Nor does it incite any great passion, they just play. They shuffle, deal, and speak only when necessary for the game to continue. And they keep a tally, point by point, dash by dash. There are no breaks, no half-time, it’s a continual performance, no winner, no loser, a cyclical journey that leads nowhere. Nobody decides when it ends, it’s an organic gesture: to play or not to play. I close in, I spy on them, I make faces at them, but they don’t notice, I don’t bother them. They raise the stakes, without risk or hesitation. Bean by bean. And me too, on the outside, although I’m not taking part in the game, I’m there, with them, half horny, half lonely, circling around them, and I’m part of it, breathing in time, or in syncopation, accepting that this is how it is, that things have to happen this way, first one, then the other, each one in turn, devising a unique, singular present, which immediately escapes the three of us, forever.

Now I see them collecting the cards in their big mitts, piling some on top of others into two decks confronting each other from an equal distance on either side of the table, Jaime’s with blue arabesques, Boca’s orange, and it looks like they’ve finished their game.

I feel a little lonely. I’ve no one to talk to about this approaching maternity.

Tomorrow is the thirtieth of October. My due date is in the middle of February, it’s all happened so suddenly, and I couldn’t do anything about it.

FORTY

We can get married. Jaime is speaking, in the dark, without showing his face. We got back from Luján a short while ago, from a barbecue at Héctor and Marta’s to celebrate the twins’ eighth birthday. We went to bed straight away, slightly nauseous from so much meat. The sheets were damp, almost wet. In the middle of the night I got up to pee. In the bathroom I looked at myself in the mirror and thought that I didn’t look quite as bad as I had in recent months. In the dark, I sensed where the bed was and lay down again on my side, the gate side. It had been that way since the beginning, me on this side, Jaime closer to the other Jaime. Dead or alive. It’s so strange to have something in my stomach that’s going to be someone. I stroke myself, I feel it with my open palm, I wait a while, nothing. I wonder when it was. That first time, when I didn’t even come?

Héctor and Marta treat me as if I’m one of the family now. The twins adore me, they say I’m their favourite aunt. I’m scared. I close my eyes to try to stop thinking and, right then, Jaime decides to speak. Wasn’t he asleep? We can get married, he says and doesn’t insist, he’s not interested in my answer, that’s all he has to say.

I re-read the notes that I’ve written over the last few months on Cabred, Huret, the colony and the lunatics, and it seems like a distant memory, adolescent and boring. There are about fifty sheets or more, the first few handwritten on both sides, the rest printed from the computer, normal type, double-spaced. I scan the pages, and it’s enough to catch a sentence or a few words at random to guess the context, I know what follows. It’s nothing more than that, a collection of sentences linked by sufficient common sense. I lost interest, I can’t deny it, and yet for almost five months my head was full of loonies: loonies on horseback, bricklayer loonies, uniformed loonies, in blue or orange, or both, blue trousers and orange sweatshirt, loonies with no clothes on, undressing in the middle of something, loonies kneading bread, hand over hand over hand, frenetically, old-style loonies, deranged, less neurotic but more insane, loonies who don’t look like loonies, who bite their lips, just slightly, like anyone else, but who only think about that, about biting their lips, loonies who are practically philosophers, who say things that leave us open-mouthed, as if to say: Look what the loony said, lost loonies, loonies who get beaten up, with clean blows, and who one day, without explanation, start to receive fewer blows, or secret blows, out of sight of the other loonies, and more, many more, all of them, dead loonies, like the one that Jaime found amongst the weeds of the nursery, almost albino, his eyes wide open, or the one who appeared hanging from a branch above the clay oven, his feet stained with soot from the smoke that kept churning out, and the loonies who no one looks for, who nobody reclaims, who they call anything, whatever name comes to them, loonies fucking, never coming, all the loonies, in a row, ready to enter the catalogue, invented loonies, who are the vast majority, because it’s easy to invent loonies, nobody makes mistakes inventing loonies, anything could be true. They’re there, even though they no longer interest me, they tell me a load of things, but it isn’t the same. I’m bored.

The dream from the other night returns, it never ends. Still in Rio de Janeiro, it still seems as though I’m going to kill them all. But I don’t kill them.

A car with tinted windows stops by the gate. It beeps three times. The first two short, the third sustained. I approach slowly. I don’t walk as quickly as before.

One of the front windows opens, on the passenger side, and Eloísa appears. She’s dressed entirely in black. A bit like a goth, but not entirely. She raises her hand, waves and shouts my name. She’s had her hair cut, it’s uneven, two long tufts cover half her face. We say hello without opening the gate. She kisses me on one cheek, then the other, and in passing she brushes my mouth. Only just. Now she extends her arms, to see me better, and she says or protests, with emotion or anger: So it was true. She strokes my belly, without really touching me much, from a distance. And you, I ask. I’m good, and in my ear: I’ve got a boyfriend. And she gestures for the person sitting in the car listening to music to get out. And he gets out, rather ungainly, his hair tousled, chewing red gum. She introduces us. They look at each other, they smile, I smile. And he says: How’s it going? Fine, I say, hi. I don’t know whether they want to come in, I don’t know whether I want them to stay. Since I’m unsure, we say goodbye. Eloísa winks at me. I hate her.

I want to talk to you, says Jaime and immediately plugs his mouth with a cigarette as if he regrets saying it. But he takes courage and continues: About what I said to you the other times, the other night, you haven’t said anything. About what? I ask and play dumb. About getting married, he says. Jaime speaks without looking at me, uncomfortable, and I can’t believe what I’m hearing. He pauses. The first thing that comes to me is: There’s no need, we’re fine like this, we can carry on like this. Jaime doesn’t answer, he smokes and becomes sad. Let’s see what happens, I say and stretch out a hand that stays in the air, like a silent word that Jaime doesn’t catch. He nods, obedient, incapable of arguing. It’s the first time a man has proposed to me.

I spend all night crying, in the dark, locked in the bathroom so that Jaime doesn’t see me.

FORTY-ONE

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Open Door»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Open Door» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Open Door» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.