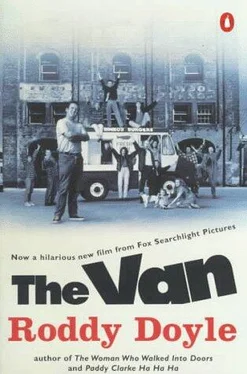

Roddy Doyle - The Van

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roddy Doyle - The Van» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Van

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Van: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Van»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Van — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Van», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was a smashing idea. They’d burst their shites laughing. And he was right, Bertie; the letter had been ammunition, like a gun nearly, in his back pocket.

— You’ve no righ’ to be readin’ my letters.

— It was just lyin’ there.

— Where?

— Inside on the shelf.

Jimmy Sr felt his back pocket again, and looked at Bimbo like he’d done something.

— Is tha’ what it’s abou’? said Bimbo.

— It’s none o’ your business what it’s abou’. It’s private.

— You don’t need to be in a union, said Bimbo.

— I’ll be the best judge o’ tha’, said Jimmy Sr; then quieter, — Readin’ my fuckin’ letters—!

— I didn’t read it.

— Why didn’t yeh tell me when yeh found it?

— I didn’t know you’d lost it.

Jimmy Sr leaned forward, to see out if there was more rain coming.

— Are yeh really joinin’ a union? said Bimbo, sounding a bit hurt and tired now.

Jimmy Sr said nothing.

— Are yeh?

Jimmy Sr sat back.

— I’m just lookin’ after meself, he said. — An’ me family.

Bimbo coughed, and when he spoke there was a shake in his voice.

— I’ll tell yeh, he said. — If you join any union there’ll be no job here for yeh.

— We’ll see abou’ tha’, said Jimmy Sr.

— I’m tellin’ yeh; that’ll be it.

— We’ll see abou’ tha’.

— If it comes to tha’—

— We’ll see.

Bimbo got out and went for a stroll up and down the road. Jimmy Sr turned the page and stared at it.

He’d gone down to the shops himself instead of sending the twins down — they wouldn’t go for him any more, the bitches — and got them sweets and ice-creams, even a small bar of Dairymilk for the dog. It had been great, marvellous, that night and watching the dog getting sick at the kitchen door had made it greater. Even Veronica had laughed at the poor fuckin’ eejit whining to get out and vomiting up his chocolate.

— Just as well it wasn’t a big bar you bought him, Darren said.

It had been a lovely moment. Then Gina waddled over to rescue the chocolate and she had her hand in it before Sharon got to her. Jimmy Sr wished he’d a camera. He’d get one.

They’d had a ride that night, him and Veronica; not just a ride either — they’d made love.

— You seem a lot better, Veronica said, before it.

— I am, he’d said.

— Good, she’d said.

— I feel fine now, he’d said. — I’m grand.

— Good, she’d said, and then she’d rolled in up to him.

But it hadn’t lasted. Even the next day his head was dark again; he couldn’t shake it off. When Darren came into the front room to have a look at Zig and Zag on the telly, Jimmy Sr’s jaw hurt. He’d been grinding his teeth. He snapped out of it, but it was like grabbing air before you sink back down into the water again.

He kept snapping out of it, again and again, for the next two days. He’d take deep breaths, force himself to grin, pull in his stomach, think of the ride with Veronica, think of Dawn. But once he stopped being determined he’d slump again. His neck was sore. He felt absolutely shagged. All the time. But he tried; he really did.

He was really nice to Bimbo, extra friendly to him.

— How’s it goin’, and he patted his back.

He whistled and sang as he worked.

— DUM DEE DEE DUM DEE DEE — DUM — DEE—

But, Christ, when he stopped trying he nearly collapsed into the fryer. You’re grand, he told himself. You’re grand, you’re alright. You’re grand. You’re a lucky fuckin’ man.

But it only happened a couple of times, the two of them feeling good working together. And it wasn’t even that good then because they were nervous and cagey, waiting for it to go wrong again.

It was like a film about a marriage breaking up.

— The cod’s slow enough tonight—

Bimbo saw Jimmy Sr’s face before he’d finished what he’d been going to say, and he stopped. Jimmy Sr tried to save the mood. He straightened up and answered him.

— Yeah, — eh—

But Bimbo was edgy now, expecting a snotty remark, and that stopped Jimmy Sr. They were both afraid to speak. So they didn’t. Jimmy Sr felt sad at first, then annoyed, and the fury built up and his neck stiffened and he wanted to let a huge long roar out of him. He wanted to get Bimbo’s head and dunk it into the bubbling fat and hold it there. And he supposed Bimbo felt the same. And that made it worse, because it was Bimbo’s fault in the first place.

Darren wouldn’t work for them any more.

— It’s terrible, he explained to Jimmy Sr. — You can’t move. Or even open your mouth. — It’s pitiful.

— Yeah, Jimmy Sr almost agreed. — Don’t tell your mother, though. Just tell her the Hikers pays better or somethin’.

— Why d‘you keep doin’ it, Da?

— Ah—

And that was as much as he could tell Darren.

— But mind yeh don’t tell your mother, okay.

— Don’t worry, said Darren.

— It’d only upset her, said Jimmy Sr. — An’ there’s no need.

There was just the two of them in the van now, except maybe once a week when Sharon was broke or doing nothing better. She wasn’t as shy as Darren.

— Wha’ are youse two bitchin’ abou’? she asked them one night after Jimmy Sr had grabbed the fish-slice off Bimbo and Bimbo’d muttered something about manners.

(It had been building up all night, since Bimbo’d looked at his watch when he answered the door to Jimmy Sr, just because Jimmy Sr was maybe ten minutes late at most.

— Take it ou’ of me wages, he’d said.

— I didn’t say annythin’, said Bimbo.

— Me bollix, said Jimmy Sr, just over his breath.

And so on.)

Neither of them answered Sharon.

— Well? she said.

— Ask him, said Bimbo.

— Ask me yourself, pal, said Jimmy Sr.

— Jesus, said Sharon. — It’s like babysittin’ in here, so it is. For two little brats.

And she slapped both their arses.

— Layoff—!

But she slapped Jimmy Sr again, messing. He had to laugh. So did Bimbo.

— How was it tonight? Veronica asked him when he got into the scratcher and his cold feet woke her up.

— Grand, he said.

Jimmy Sr looked at Bimbo sometimes, and he was still the same man; you could see it in his face. When he was busy, that was when he looked like his old self. Not when he was hassled; when he was dipping the cod into the batter, knowing that time was running out before the crowds came out of the Hikers. In the dark, with only the two lamps lighting up the van. A little bit of his tongue would stick out from between his lips and he’d make a noise that would have been a whistle if his tongue had been in the right place. He was happy, the old Bimbo.

That wagon of a wife of his had ruined him. She’d taken her time doing it, but she’d done it. That was Jimmy Sr’s theory anyway. There was no other way of explaining it.

— Look it, he told Bertie. — She was perfectly happy all these years while he was bringin’ home a wage.

— Si—, said Bertie in a way that told Jimmy Sr to keep talking.

— She was happy with tha’ cos she thought tha’ that was as much as she was gettin’. Does tha’ make sense, Bertie?

— It does, si. She knew no better.

— Exactly. — Now, but, now. Fuck me, she knows better now. There isn’t enough cod in the fuckin’ sea for her now. Or chips in the fuckin’ ground; Jaysis.

— That’s greed for yeh, compadre.

— Who’re yeh tellin’.

It was good talking to Bertie. It was great.

— It’s her, said Jimmy Sr. — It’s not really Bimbo at all.

— D’yeh think so? said Bertie.

— Ah yeah, said Jimmy Sr. — Def’ny.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Van»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Van» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Van» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.