— Far as he knows, said Outspan.

Les laughed.

— Les had the same version as me, Jimmy told Des. — But he’s grand now. Righ’, Les?

Les nodded.

Des would be fine. He’d already known about Jimmy, and Jimmy had warned him about Outspan — although a warning could never come close to meeting the man himself. So Les was the only surprise addition.

It was getting cold. Jimmy could feel the damp pawing his arse, and he was ready for another piss. But he felt great. The anxiety had gone out of his neck and shoulders and the burger was probably the best he’d ever eaten. He didn’t give much of a shite about food. But it was the context — the time, the place, the company, the hand-cut chips.

— Could’ve done with a bit more salt, Liam.

— Fuck off.

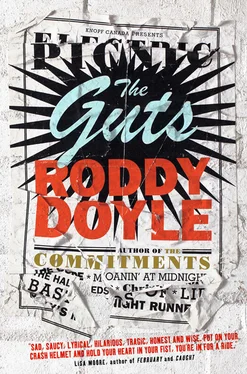

None of Jimmy’s acts were on till the next day, the Saturday. He had the Halfbreds and the Bastards of Lir, Ocean’s da’s poxy band, and the one he was planking about — and giddy about — Moanin’ At Midnight. He was a free man till then.

He smiled at Des. He lifted his beaker.

— Another?

— Go on.

Outspan threw his empty beaker across at Jimmy. Jimmy waited for him to send a twenty across with it. But not for long — Outspan’s hands didn’t go anywhere near his pockets.

Des stood up with him.

— I’ll give you a hand, he said.

— I’m going via the jacks, said Jimmy.

The place — the park, whatever it was; the grounds — it was really filling now. Going anywhere in a straight line wasn’t an option. It was vast, it really was. But they spotted a sign for the jacks. They sank a bit, but they were grand — they were okay. It was a bigger version of the jacks back in Darfur, and already well broken in. They got places beside each other at another yellow urinal. Jimmy held the empty plastic beakers high in his left hand.

— The Olympic torch, said a young lad on the other side of him. — Cool.

— The Paralympics, said Jimmy.

Des laughed. So did the young lad. This was the life. Des held the beakers while Jimmy did his buttons.

— You enjoyin’ yourself, Des?

— Watching you doing your fly?

— No, I was takin’ that for granted, said Jimmy. — I mean — overall.

— Yeah, said Des. — But —

— Go on.

— I can’t pay for anything. I’ve enough for a couple of rounds —

— You’re covered, said Jimmy. — That was always the deal.

— Thanks.

— No. But actually, it’s Outspan — that’s Liam — you should be thankin’.

— I like him.

— Yeah.

— Is he definitely —?

— Yeah, said Jimmy. — There’ll be no happy ending there.

— Fuck.

— Yeah, said Jimmy.

The queue for the drink still wasn’t too bad. It was hardly a queue at all, more a slow walk. Out of Darfur, the average age had shot up. Jimmy and Des might have been the oldest in the line, but not by too much. Women too, hitting the forties.

They were closer now to two of the music tents.

— That’s the Crawdaddy, I think, said Jimmy.

He pointed at the one on the left.

— A lot of the good stuff, our kind o’ music, yeh know. It’ll be in there.

— Ol’ lads’ music.

— Discernin’ oul’ lads. Exactly.

He handed over the beakers to the young one behind the counter. He didn’t even have to tell her what he wanted, and she never asked. He had to hand over the twenty before she went off and filled them. He didn’t thank her and she didn’t thank him.

— A bit soulless, isn’t it? said Jimmy.

— Fuck it, said Des.

They got back to Outspan and Les. It felt good, seeing them there, sitting side by side, staring out at the world. It was like he hadn’t seen them in ages, years, and — in a way — it was true. It was just a sentimental thought. But grand. His head was nicely fuzzy.

They sat and watched the world wade by.

— Jesus, the height of her.

— My God.

— Is she WiFi enabled?

It was time to move, stretch the legs — Jimmy was numb. They all were.

— My leg’s gone dead.

Les held onto Jimmy’s shoulder while he shook blood back down through his leg.

— Fuckin’ oul’ lads, said Outspan.

He looked like the only one ready to bop.

They liked being the oul’ lads. It was safe, relaxing; nothing was expected or demanded. They could go spare or give up; it didn’t matter. No one would give a shite, especially them.

Maybe.

They gathered up their rubbish and found a bin.

— Goes against my fuckin’ principles, said Outspan. — So where’re we goin’?

They strolled across towards the Crawdaddy tent. It looked a bit like something out of a children’s book — the candy-stripe roof — and they weren’t the only people heading into it.

— It’s like the end of Close Encounters , said Jimmy.

They walked into the dimness of the tent and the smell of dead grass. The ground was wet but it was fine. The feet weren’t sinking.

But something wasn’t right. The people around them were too young. They weren’t Grandaddy people. Grandaddy had been around for years, long enough to break up and re-form. Their one great album, The Sophtware Slump , had been released around the time Mahalia had been born, maybe a bit after. Jimmy got the programme out of his back pocket.

— Sorry, lads. Wrong tent.

— Ah, yeh fuckin’ eejit.

They got out and moved across the field, to the Electric Arena. They had to go at a stroll, to let Outspan keep up with them, but they got into the tent — it was huge — in time to see a big gang of beardy lads walk onstage.

— This them?

— Yeah.

— Who are they again?

— Grandaddy.

A few people whooped, a few more clapped, and the usual eejit started shouting the name of a song.

—’The Crystal Lake’! ‘The Crystal Lake’!

There was no messing or tuning. The band got going and the tent quickly filled and warmed up. They were great. They were brilliant. There was no encore. The band bumped to a good end and walked off.

— What did yeh think?

— Shite, said Outspan.

— Good, said Des.

— Not my kind of thing, said Les. — But they were thoroughly professional.

They went back out, for a piss and a drink, and back in for Grizzly Bear.

— What did yeh think? said Jimmy.

— Shite, said Outspan.

— Yep, Jimmy agreed. — I expected more.

— Yeh poor naive cunt.

They were outside again, and across the field to the bar. Les bought the round.

— Fucking expensive this side of the pond.

Fuckin’ eejit, Jimmy thought, but he wasn’t sure why. Because it was fuckin’ expensive. No one was tearing off to the jacks this time.

— We’re gettin’ the hang o’ this.

— Becomin’ acclimatised.

— Jesus, lads, said Jimmy. — Two gigs down an’ it’s still daylight.

— Marvellous, said Les. — What’s next?

Mark Lanegan, in the Crawdaddy.

— Fuckin’ who?

Jimmy gave Outspan the history — Queens of the Stone Age, The Gutter Twins, Isobel Campbell, Soulsavers. Lanegan walked out and he was immediately their man. In a dirty black suit he stood at the microphone, held it, looked at the ground when he wasn’t singing and said nothing between songs. And the songs were great — straightforward, hard, three minutes. Jimmy could feel the sound as a physical thing, thumping his chest, even flapping the sleeves of his hoodie. Lanegan had pulled the crowd in; the tent kept filling. There was a fair bit of good old-fashioned head banging going on around them. Jimmy looked at his own gang. They were loving it.

— What did yeh think?

— Shite, said Outspan.

— Ah, for fuck sake.

Читать дальше