The fish get plated alongside scoops of greenbean casserole and hunks of fresh bread. Synnøve pulls an extra folding chair from a hallway closet, passes some cucumber salad around. Stanley watches carefully before he takes a bite of anything.

Everyone eats the fish whole — bones and all, like sardines — but they don’t taste like sardines. Stanley remembers small fish that his Italian neighbors cooked around Christmastime, in those years when his father was away and his mother wasn’t speaking and he had to take meals wherever he could find them: these taste a little like those did. As he chews he thinks of the seething silver carpet on the moonlit sand, and also of the bag of heads by the backdoor — the tangle of guts, the little mouths working, the cloudy unblinking eyes— making himself think these things. But they don’t really bother him. The fish taste good. He’s hungry. He hasn’t had a proper kitchen-table meal in months.

Welles keeps standing up and sitting down, splashing pale gold wine into half-empty glasses. Soave classico , he says. I’ve had these bottles for more than a year. It’s lucky I saved them! For this meal it’s just right. Fish on Friday! My god, are you angling to re-Catholicize me? Well, it may be working, damn it all, it may be working.

The guy is keyed up, on a roll; nobody makes much effort to share the stage. Synnøve and Cynthia each get in some good licks, and Claudio slow-pitches a few earnest questions, but mostly they just let Welles wind himself down. Stanley feels like he’s watching a swordfight in an old movie where the hero — Errol Flynn, maybe, or Tyrone Power — holds off a dozen guys at once, only none of them seem to be trying very hard to scratch him. Cynthia keeps raising her eyebrows, smirking. Welles talks with his hands, barely touches his food. Stanley finds it all sort of depressing.

Speaking of Catholicism, Welles says, and then recites part of a poem, something he just wrote. Stanley clenches his jaw, stares at his plate, pushes a french-cut greenbean around with a tightly gripped fork. Thus does faith fold distance! Welles says. So bend the Ptolemaic rays! And Poor Clare perceives, ether-borne, the priest’s vestmented image on the wall . Please stop, Stanley thinks. Stop spoiling it. Stop talking.

I suppose you’ve heard, Welles says, that the pope just named Clare of Assisi the patron saint of television. Two or three weeks ago, I think. Rather more inventive than declaring the Archangel Gabriel to be the patron of radio, wouldn’t you say? But then the church has always been quite comfortable with the concept of the discarnate word propagated through space. Less so with the discarnate image. The pope had to work a little harder to locate divine precedent. Lately, as I write, I’m finding myself drawn to stories such as these. It seems that this is what the new work will be about . The power of the image. The image of power.

Cripes! Cynthia says. Get a load of the clock! We better cut out, kemosabe. The curtain goes up at tick sixteen.

She and Claudio retreat to the entryway, Claudio clasping hands and murmuring thanks as Cynthia passes him his jacket. Stanley gets up, catches Claudio in the hallway, hands him some folded bills. For the movie, he says.

Claudio palms them with a guilty look that quickly passes. You will be here when I return? he says.

Here, or at the squat.

You should stay here, Claudio says. I like it here.

Synnøve is clearing the dishes; Welles moves through the livingroom — still eating from the plate in his hand — to put an LP on the turntable. Cynthia glides over to the two of them in turn, planting kisses behind their ears. Claudio and I had better trilly, she says. Don’t wait up for us.

Take it slow, Stanley tells Claudio as he steps outside. Keep your eyes peeled.

We will not go to the Fox, Claudio says with an irritated backward glance. We will go to a nice place.

The door closes. Stanley watches them through the window as they chase a couple of cats off the lawn. He feels a funny prickle in his sinuses, a sore tremble in his throat. He wonders what his goddamn problem is all of a sudden.

Music crashes from the hi-fi: a crazy choir chanting in some weird language while woodwinds and tympani toot and boom behind them. Welles leans into the entryway, shouting over the racket: Synnøve and I will do the washing-up, he says. You should go upstairs and poke through my library. Borrow something you think you might like. I’ll be up in a minute with a couple of beers. Does that sound good?

On the narrow staircase Stanley feels dizzy, slows down. He rarely drinks, doesn’t much care for the drowsy off-balance feeling he gets. He lifts his feet, plants them again. His pulse throbs in his wounded leg.

As he comes to the top the air changes, becoming dry and close and old. There’s a strong odor of pipesmoke, and another smell beneath it: paper, fabric, glue, the invisible insects that eat such things. Even before Stanley finds the switch on the table lamp, he feels the books. With every step he takes across the creaking floor the whole house seems to shift, the contents of the cases to strain against each other on their shelves.

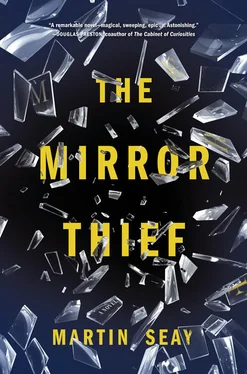

In the weak yellow lamplight, Welles’s offer becomes ridiculous: Stanley could search this room for hours and find nothing to interest him. Books on economics and nuclear energy and the history of Italy, books about metallurgy and glassmaking and electronics, books in other languages. A lot of them remind Stanley of The Mirror Thief , but not of anything that he likes about it. After a few minutes of browsing he loses interest, shifts his focus to the room itself.

The study takes up nearly half the floor. On the west wall a french door between two curtained windows opens onto the moonlit deck. In the middle of the opposite wall there’s a heavy black portal with a regular deadbolt plus a massive external sliding bolt, like something out of a medieval fortress. Curious, Stanley throws the big bolt — the loud hi-fi downstairs swallows the noise — and tugs on the knob, but the door is locked. He puts the slider back the way he found it, transfers his attention to Welles’s desk.

It’s immense: polished teak, ornately carved. Several peculiar paperweights — a bronze pelican, a clear glass hemisphere with colors swirled inside it, a jagged hunk of metal that looks like part of an exploded shell — are clustered at the lower right corner, probably to catch rollaway pens and pencils, since that’s the way the floor slopes. A few sheets of rose-white paper sit on the blotter, crowded with handwriting, steeply slanted and illegible. Next to them is a letter, still in its ripped-open envelope, from someone in a hospital in Washington, D.C. Stanley pays these little mind. With one ear cocked toward the stairs he begins to open the drawers, to scan their contents.

They all have fancy brass locks, but none is locked. The first one he opens — the long shallow one in the middle — contains a pistol: a.45 automatic, 1911 model. Stanley guesses it’s got a round already chambered, but opts not touch it to learn for sure. Seated in the swivel chair behind the desk, Welles could get to it in a hurry. Two drawers down on the right Stanley finds a second pistol, a Wehrmacht P38. If Welles keeps this stuff stashed in his study, what’s hidden in his sock-drawer? A greasegun, maybe. Or a bazooka. The guy probably drives to work in a tank.

On the wall behind the desk hangs a framed map. Stanley figures it for a map, anyway: it shows a club-shaped island city the way it might look from a plane flying by, though not directly overhead. The perspective strikes Stanley as strange, because the style of the map makes him think it was made a long time before there were any such things as airplanes — like whoever drew it had to close his eyes and project himself into space, and then to hold the picture of the city in his head while he nailed down the streets and canals and houses on paper. Remembering all he could. Imagining the rest.

Читать дальше