On the sidewalk south of his hotel, some motorcycle cops and security officers are arguing with five or six young LaRouche canvassers who’ve been hassling passersby with placards and brochures. The kids point and shout; one of the cops talks into his radio. THE METHODOLOGY OF EVIL, the kids’ placards read. STOP OLIGARCHS IMPEACH DOGE BUSH! CHENEY’S NUKES OR GREENSPAN’S DOLLAR — WHICH WILL *BLOW* FIRST? Curtis imagines Walter Kagami in his Cosby sweater, chanting through a bullhorn as the police load him into a paddywagon. Curtis isn’t sure yet how he feels about the war, but he doesn’t envy Walter. It’s got to be hard to hate something so much when you know there’s no chance in hell you’re ever going to stop it.

The speech hasn’t ended by the time they pull into the porte-cochère, but Curtis has gotten the gist. He passes the envelope of bills over Saad’s shoulder and opens the door. Your eye is okay? Saad says. You are sure? I can take you to a doctor.

It’s fine, Curtis says. I’ll fix it when I get topside. You working tomorrow?

Yes, Saad says. Tomorrow I will work.

You might hear from me again. I may need a ride to the airport.

You have my number. Good luck, my friend. Stay out of the casino!

Thanks! Curtis calls. Keep off your roof! But Saad is already pulling away, and can’t hear him.

When he slides the keycard and opens the door, Curtis spots a steady flash on the nightstand: the phone’s message-light. Jersey cops, no doubt. They’ve been waiting three hours, probably, for a callback. Curtis figures another few minutes won’t kill them. Or anybody else.

He throws his jacket on the bed, opens his suitcase, unzips the mesh pouch on the underside of its lid and removes the Ziploc that hold his saline and peroxide and suction device. Then he carries the bag into the head and turns on the light.

He takes off his safety glasses, washes his hands, washes his face. Then he scrubs his hands again, past the elbow this time. When he’s done, he unwraps a glass tumbler and spreads one of the hotel’s fluffy white towels over the sink.

The spotless mirror and the bright overhead lights don’t make it any easier to see where the problem is. Could be an allergic reaction, or maybe he’s just dehydrated. He pulls back the lids to take a good look.

It’s still amazing to him: the tiny pink fibers in the offwhite sclera, the individual cords in the mouse-gray iris. The ocularist at Bethesda did a hell of a job. Between the bumpy ride south from Gnjilane and waking up blind and terrified in Landstuhl he remembers next to nothing, certainly nothing of the accident. Things get a little clearer later: sitting on the runway at Ramstein, trying to understand through the painkiller haze why the plane wasn’t taking off. We are not flying, Gunnery Sergeant, because nothing is flying. The FAA ordered a ground stop of all flights, civilian and military, within or bound for U.S. airspace. No sir, nobody knows, because this has never happened before . At the time it seemed like everything was wrecked, like nothing would ever be the same. And nothing has been, really. But it’s been surprisingly easy to forget the specifics of what’s changed, to forget exactly how he got hurt, to forget what he can and cannot see.

Curtis wets the suctioncup with a squirt of saline, pinches its rubber bulb, and presses it to his acrylic cornea. Then he pushes down his lower eyelid with his thumb, and the prosthesis drops into his damp left palm.

He puts it in the hotel’s tumbler and covers it with peroxide, then parts his lids again to peek at the blank curve underneath: the orbital implant’s white coral sphere, filmed with conjunctiva. On the countertop, the prosthesis stares up through the peroxide bubbles. Thin, hard, curved. Its smooth edges nearly triangular, like a worry-stone.

As he’s flushing his empty socket with saline, his cell rings. He towels his face, steps into the bedroom to pick it up. A local number, not one he knows. He thinks for a second about what Argos told him. Then he presses the green button. Yeah, he says.

Curtis, it’s Veronica. Where are you right now?

A swirl of ambient noise around her voice. Nothing he recognizes. At my hotel, he says. What’s up?

Listen, I just talked to Stanley. He’s flying back from AC tonight.

Curtis blinks. Okay, he says.

He’s been dealing with Damon. Curtis, your buddy is fucked. The Point put an exclude-eject on him, and now I’m hearing about an arrest warrant, too. I don’t begin to follow what’s going on, but Stanley is coming back, and he wants to meet with you.

Curtis hears a PA behind her voice: pages, security announcements. She’s at the airport. At the end of the suite evening light pours through the windows, making a golden band across the final feet of the left-hand wall. Not much of it is getting to Curtis. He switches on the bedside lamp. The moment he does so, the fax machine across the room begins to hum.

Curtis? You still there?

Yeah. I’m here.

Did I catch you at a bad time?

No, Curtis says as he moves across the room, reaching for the paper as the machine spits it out. No, it’s fine. Hey, uh — is there any chance you could call me back on a landline? On my hotel phone?

No time. Sorry. Stanley’s plane is gonna be wheels-down in like five minutes. Can you meet or not?

The paper in Curtis’s hand is mostly black. Its thick border seems at first to be squiggles — like someone was trying to get a cheap inkstick started — but resolves instead into a grisly thicket of anatomy: cunts and cocks and balls, unspooled intestines, shattered skulls spilling like cornucopias. Each corner is adorned with the image of an eyeball, trailing an optic nerve like a kite’s tail. In the middle of the crowded page is a message. YOUR FUCKT TRATER, it reads.

Sure, Curtis says. I can meet. When and where?

The Quicksilver. Walter hooked us up with a room. Just go to the bell-desk and give your name. They’ll have a keycard for you. If we beat you there, they’ll just give you the room number.

You won’t beat me there, Curtis says.

He crumples the fax as he looks out the window. A plane, maybe Stanley’s, is dropping toward McCarran now. On the wall by Curtis’s shoulder the murky painting is bathed in amber. Most of its vague details vanish in the glow, but others emerge. In a lower corner there’s a sea-monster that Curtis never noticed before.

Hey, Curtis? Veronica’s saying. One more thing. Can I ask a favor?

Yeah. Sure.

Can you bring Stanley’s book when you come? I think he’d like it back.

No problem, Curtis says, but Veronica is already gone. He stares at his dead phone for a few seconds, then pockets it.

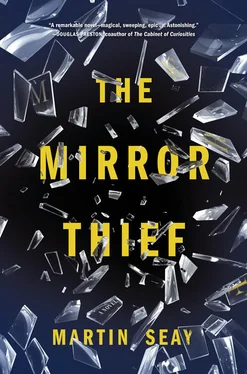

The Mirror Thief sits on the circular table, inches from his hand. Although Curtis didn’t get much from it aside from a headache, he somehow wishes he’d read more. As he lifts it through the sunbeam, the flecks of leftover silver on the binding flash gold.

On his way back to the head to replace his prosthesis, Curtis notices the tracks that his desert-filthy shoes have made across the carpet: pale alkaline rings for every step, like the footprints of a ghost.

And the waters richer than glass

Bronze gold, the blaze over the silver,

Dye-pots in the torch-light,

The flash of wave under prows,

And the silver beaks rising and crossing

Stone trees, white and rose-white in the darkness,

Cypress there by the towers,

Drift under hulls in the night.

— EZRA POUND, Canto XVII

Gulls’ voices wake Stanley. His eyes open to the sight of motes adrift in the pencil-slender sunbeams that pierce the boarded-up back window of his and Claudio’s lair. He wasn’t dreaming about New York just now, but the light still seems wrong, like it should be coming from the other direction. He sits up, rubs his face, listens to noises from outside, sharp in the cool spring air.

Читать дальше