The crown of a second tower — brick, square, topped by a steep pyramid — appears and disappears in the spaces between rooftops. As they draw close, it seems to grow taller, thicker, greener at its tip. They cross jade canals, slosh through puddled corridors, and emerge into a colonnaded square swarming with white doves. Startled into flight, the birds ripple like foam across the gray sky. The great belltower catches their shadows. Curtis knows this place, too.

He’s alone now, moving forward between the tower and the domes of a gilded basilica, rounding the corner of a grand hall and looking out at the churning sea beyond. There’s a small group of ragged gamblers on the quay up ahead, gathered between two marble columns, throwing dice below the stinking corpses of hanged men. As he approaches, Curtis sees Stanley crouched over the tumbling cubes. Stanley looks up and smiles, and Curtis can see that he’s dead: his flesh sagging, his eyesockets black voids. He offers Curtis the dice with a withered hand, and Curtis declines. The dead Stanley turns and hurls them with tremendous force, aiming at an island on the lagoon’s distant edge. If they hit the water, Curtis doesn’t see the splash.

The gamblers are gone. Curtis pushes through crowds of camera-slung tourists, self-conscious in his hospital gown; he crosses a bridge to the entrance of the Doge’s Palace, and he’s in the casino again, just left of the high-limit slots. He works his way toward the elevators, eager to get back to his bed. As he passes the Oculus Lounge he scans the tables for Veronica, then for Stanley, and finally for the kid he chased last night. Thinking back, replaying it in his head, Curtis is embarrassed for both of them. The Whistler with his little mirror, Curtis with his fumbling pursuit. Grown men playing at being detectives, spies, criminals. Damon too, with his scheming and his faxes. And Stanley. Stanley with his whole life. But Curtis — who has seen misery and death in seven countries, who has been broken and imperfectly rebuilt, who should at this point know better — Curtis worst of all.

He’s awake now.

It takes him a minute to find the book in the sheets. He spent most of last night reading it: in Veronica’s room, after she fell asleep on the couch, then here, until he dozed off himself. He wipes his eyelids, reaches to turn off the lamp on the nightstand.

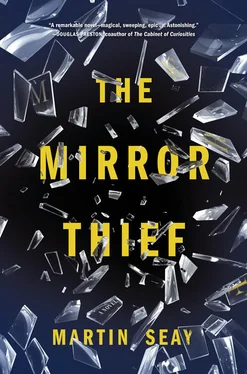

The Mirror Thief . Curtis can’t make heads of tails of it. So far as he can tell, it’s mostly about a guy named Crivano who’s some kind of wizard. Other people are in it, too: somebody called Hermes, somebody called the Nolan. The moon has a speaking part. Sometimes it seems like a plot is coming together, but then a six- or seven-page poem comes along — about the business of alchemy, or the technology of glassmaking, or the relationship of metals to planets — and the story gets put on hold. It’s all supposed to be very smart and serious, but at the same time there’s something goofy and Dungeons-&-Dragons about it, too.

Lust and war! The Gorgon’s stony gaze

masks the inner limit of the body—

adulterers ensnared by such silk thread

as spiders hoist upon the rafter-beam.

Web-spinners, mirror-makers, Athena

Parthenos and her ill-shaped sibling

shield the lexicon of craft and trick:

the redirecting flash, the circle-step

made sideways on back-turned feet, as

the logarithmic nautilus records.

Crivano, too, moves along such spirals.

Curtis is sure there are clues that he’s missing. At the beginning, for instance, a page has been razored out — the second printed page, the title page, with publication data on the back — cut evenly, close to the spine, so just a sliver of paper remains. Tomorrow, when the libraries are open, he’ll call around, see if he can’t scare up an intact copy.

He throws off the covers, makes the rack. No faxes, no messages. He opens the curtains, drops to the deck, and does two minutes each of pushups and situps. Fast, not counting. Timing himself off the little clock on the CNN crawl. Onscreen, Chinese people in surgical masks. Girl run down by a bulldozer in Palestine. Still no war. Curtis sits up, cycles through channels: BET, USA, Disney, PAX, History, Travel, TV Land.

He showers, shaves, gets dressed — gray slacks, brown crewneck pullover — and checks himself in the mirror in the sunken livingroom. He remembers the weird hallucination from last night, then thinks of the dead Stanley in his dream. Curtis steps closer, watches his own reflection for a long time. As if expecting it to offer him advice. The sky over the Strip is deep ultramarine with a dusting of high cirrus, and the shallow crescent scar to the left of his nose is prominent in the sidelong morning light. He slips on his glasses and it vanishes under their slender black rims.

Curtis steps into the bedroom, strips down the rack, makes it again. Stretching the sheets tighter this time. Bouncing a Louisiana statehood quarter off it when he’s done. He sits in the chair by the window to think, spinning the coin on the wooden table. At first he’s doing this to keep his hands busy; then he’s just doing it. He flips the quarter off his thumbnail, tries to follow the arc, to catch it in the air. Listening to its fluttering chime: a perfect sound when he connects just right. It comes down with a slap in his cupped palm: heads or tails. It’d be nice if there was something he could decide this way. He comes up with these new systems that don’t make any sense at all, that have nothing whatsoever to do with probability . A coin toss is fifty-fifty; the odds of a natural twenty-one are — what? Five percent? Curtis can’t remember. In Stanley’s mind, about the least interesting thing you can do at a blackjack table is win money . Curtis’s attention wavers; the coin drops, he stoops to pick it up. Running the pad of his thumb over the outlines of its little pelican, its tiny trumpet. He thinks about phoning his dad, but then doesn’t.

At ten o’clock the maid knocks on the door. Curtis puts his blazer on and lets her in, chatting a little in Spanish. She’s quiet, her gaze tightly policed. If she’s surprised at the tidy rack it doesn’t register. When she disappears into the head, Curtis clips his revolver onto his belt, closes the safe, and goes below to look for Stanley.

He buys coins from a change dispenser in the slot area, not far from where he spotted the Whistler, then exits through the Doge’s Palace to catch the trolley south. He swaps his glasses for shades as he hits the sidewalk, surprised by the coolness of the outside air. The pedestrian overpass takes him across to the Treasure Island side, where he passes the two frigates becalmed in Buccaneer Bay, the dormant volcano fountain. The massive right-angled façade of the Mirage doubles itself in its mirrored windows, and Curtis stops under its covered entrance to wait. The sun is still climbing. The sky below is flat, muzzy, lemondrop-yellow, a screen behind the mountains. Duststorms somewhere to the east. Curtis thinks of the painting in his room: its muted colors and indistinct shapes. Across the Strip, through the palmtrees and the fountain-spray, his hotel’s grooved brick belltower is frontlit by the Mirage’s reflective glass; he watches the golden light play across it. The trolley pulls up to the curb, then pulls away, and Curtis is still standing there, jangling coins in his closed fist.

He had the right idea in choosing his hotel. Everything he’s done since then has been wrong. There’s not an inch of sidewalk here Stanley hasn’t stepped on, not a single table he hasn’t taken money from. Every time Curtis wakes up in this town, he walks out into Stanley’s head. He’s got to start hearing the echoes, seeing the ghosts.

Читать дальше