Lots of people get religion in their old age, Curtis. They go to church. They don’t hit the tables at Caesars Palace. This is more complicated.

Veronica’s eyes are locked on the book. Curtis can’t tell how she feels about him holding it, but he’s definitely got her attention. Maybe Walter’s right, she says. Maybe Stanley ought to be locked up. Off playing cribbage in a home someplace. Maybe that’d be the best thing for him.

How long has he been interested in this stuff? Magic. Kabbalah.

Veronica smiles wanly. It’s not totally accurate to say he’s interested in it, she says. I’m interested in it. So I fall back on it to explain Stanley to myself. That’s how I got mixed up with him in the first place. He was one of my regulars when I was a dealer at the Rio. We got to talking. He wanted to know about the post-Pico Hermetic-Cabalist tradition in early-modern thought. I wanted to know how to exploit the gaming industry to pay off my student loans. So we were pretty much thick as thieves right off the fucking bat. Stanley’s never been hung up on specifics, though. The notion of creating a system or being enslaved by another man’s — that’s not what Stanley’s about. He doesn’t give a shit about gematria. He’s only interested in what it can do.

What can it do?

According to the tradition, it can divulge correspondences hidden throughout all of creation, and ultimately reveal the secret names of God. Since the universe was created through the godhead’s utterance of its name, knowing these names theoretically gives you direct access to the divine essence, and the power to transcend space and time. Which comes in pretty handy when you’ve got clients in from out of town and you need a couple dozen tickets to Cirque du Soleil.

You believe in that stuff?

Fuck no, Veronica says. But I am interested in what happens when people do believe it. When I was in grad school, I thought all those people dropped off the face of the planet not long after 1614, when Isaac Casaubon determined the correct date of the Corpus Hermeticum . Now I find myself raiding America’s casinos with one of them.

She sips her drink and watches Curtis’s hands. He tracks her gaze back to the book. Its coffee-brown cover looks blank in the dim light, but Curtis feels imprints in the thick paper, and leans toward the lamp to read what’s stamped there.

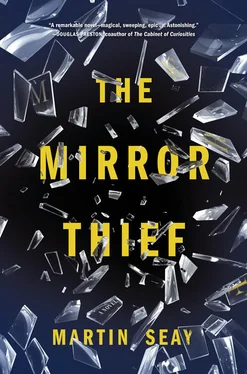

THE MIRROR THIEF , it says. The writing must have been filled with something silvery at one time; tilting the book forward, Curtis can make out a few starlike flecks clinging to the edges of the letters. He remembers, or imagines, Stanley’s fingers dusted with that fugitive silver, twinkling in the halflight of a smoky club, some dive in Chelsea or Bensonhurst or Jackson Heights. Stanley laughing, cutting the cards.

You know what you’ve got there? Veronica says.

I’ve seen it before.

That’s Stanley’s favorite book. He’s had it since he was a kid. These past few months he’s been reading it just about all the time.

Funny that he didn’t take it with him.

Yeah. It is.

Curtis opens the book. On the first page, there’s a handwritten message in faded blue ink. Crazy antiquated script.

Stanley—

Remember this always:

“Nature contains nature, nature overcomes nature, and nature meeting with her nature exceedingly rejoices, and is changed into other natures. And in another place, every like rejoices in his like, for likeness is said to be the cause of friendship, whereof many philosophers have left a notable secret.”

Best wishes to a fellow lunatic! May fortune speed you toward your own opus magnum .

Regards ,

Adrian welles

6 March 1958

Stanley knew this guy?

I don’t know how well he knew him. He tracked Welles down when he was living in California. Stanley never told you this story?

Curtis flips to the next page. Turn away, you spadefingered architects of denunciation! it begins.

Turn, you stern merchants of forgetfulness,

you mincing forgetters of consequence, turn!

Tend to your sad taxonomy, your numb ontology,

your proud happenstance of secular wheels!

Nothing thirsts after your pungent spray. Nothing

yearns to dry its hands in your grim catalogues.

Cast your auditing stares elsewhere! Bold Crivano,

the Mirror Thief, skips quicksilver on your ancient stones,

trundles his dark burden through viscera of cloud,

swaddled in the damp folds of linden-scented night.

Harry him not with your snares of causality!

Spare him the gnashing of your mad abaci!

Grant him safe transit, you squat sundial kings

(all of you polishing gold to shame silver)

for the treasure he bears in his butterfly sack

is none other than that foremost reflector itself,

the genderless Moon!

Let him pass, and mark not

his passage,

save by sleep-talking

a quiet threnody

in your dreamvoided dark.

What in the hell is this, Curtis says.

Adrian Welles, Veronica says — sounding bored, automatic, like she’s spoken or heard this many times before — was a poet active in the 1950s and early ’60s, loosely associated with the Los Angeles Beats.

Curtis flips ahead, across pages of verse, some in neat columns, some sprawling on the yellowed paper. Toward the end, his eye alights on a line —his flute conjures a harvest of sleep from the little fields of the dead —that he can hear clearly in Stanley’s voice. He’s sure he’s heard Stanley quote it, though he can’t recall when, or why, and after a moment the memory is lost. Curtis riffles backward, as if to shake Stanley’s voice from the book again, until he’s at the beginning; then he shuts the covers, presses them between his palms. The old wraps smooth, like taut skin. He almost expects to feel a pulse.

Veronica is looking out the window. Her eyes are bright, full, like she’s on the verge of tears or panic, but her breath is steady. She’s pulled her legs into full lotus, and she’s absently waggling the big toe of her left foot between her thumb and her index finger. Its shadow appears and disappears on the cushion beside her. Its red nail glistens like a coral bead.

If you want to figure Stanley out, she says, which I do not recommend trying, then that book is probably as good a place to start as any.

This guy — Welles — he was some kind of beatnik?

More like a proto-beatnik. He was an older poet, sort of an also-ran, and he gave the bandwagon a push in the early days. He was on the scene, but not really of the scene.

Curtis shakes his head, sips his drink. The bourbon is sneaking up on him. It feels like he, the book, and Veronica’s eyes are the only motionless things in the room. Everything else is drifting, leaves on a pond.

And Stanley got this from Welles?

Veronica closes her eyes. He thinks for a moment that she’s gone to sleep. When she opens them again, they’re trained on Curtis’s face.

I can’t believe Stanley never told you this story, she says.

Nothing out of place and yet everything was, because there existed between the mirror and myself the same distance, the same break in continuity which I have always felt to exist between acts which I committed yesterday and my present consciousness of them.

— ALEXANDER TROCCHI, Young Adam

Low clouds gather over the Pacific, cushioning the winter sun as it drops, and the beachcombers are coming in. For a moment the colonnades are unshadowed, and a rosy glow lights the winged lions on the frieze of the St. Mark’s Hotel.

Читать дальше