Curtis tries to take a deep breath but chokes on it, and for a second he’s afraid he’ll puke. The room spins, like the restaurant at the Stratosphere, and he shuts his eyes to make it stop. He’s thinking back, trying to recall: what time he phoned his dad, what time Damon’s last fax came. What he might have caused, or failed to stop.

Damon hadn’t shown up for work that day, the agent says. Risk Management conducted a search of his office. The story is, they found nothing on his computer but porn videos, and nothing in his filing cabinets except dirty cartoons. Pretty disturbing stuff, from what I hear. People are wondering why it took so long to realize he was a problem. He must be a real charming guy.

Curtis hears a rustle as the agent flips through his notebook, maybe looking over what he’s just written. Do you have any thoughts, he says again, as to where we might find him?

Curtis keeps his eyes shut, steadies his breath.

I have to say, the agent goes on, he picked a pretty good time to be a fugitive. As of Monday night, law enforcement nationwide is on orange alert. That’s because of the war. With everybody on defensive footing, investigations are going to slow down. An elevated alert can make it harder to hide a vehicle, though. Damon probably knew that. His Audi turned up a few hours ago, at a park-and-ride in Maryland.

Curtis opens his eyes. Maryland where? he says.

College Park. We’ve got CCTV of Damon boarding the inbound Green Line. I know what you’re thinking, and don’t worry: your dad and his wife are safe. We’ve got them in a hotel. Their home is under surveillance. If Damon shows up there—

He won’t, Curtis says. He’s gone. If Damon went to D.C., it was to get help traveling. Visas, passports. People there would do that for him.

The agent doesn’t like that answer: he looks irritated, confused. He opens his mouth, but Curtis cuts him off. You understand who we’re talking about here, right? Have you pulled his DD 214?

His what?

His service record. You ought to look at that. Look at what he’s done, where he’s been. He’s not in D.C., man. He went to BWI, or to National. He got on a plane. He could be anywhere by now. South America. Asia.

The guy is about to argue the point, but then gives up, deflates. His mouth hangs open for a second; he shuts it, rubs his face. Curtis feels bad for him, feels bad generally. He doesn’t want to believe what he’s just heard — habit works his brain hard, plugging in scenarios and explanations that put Damon in a better light — but he knows it’s true. His whole life he’s never understood anybody, not even himself. Himself maybe least of all. He wants to go to back to sleep, to slip out of a world where shit like this can happen.

Wait a minute, Curtis says. What about Stanley Glass?

The agent’s eyes open; his inkstick clicks again. Stanley Glass, he says.

Where is he?

The agent shrugs. Still in Atlantic City, he says. Last I heard, NJSP was looking to bring him in. They didn’t have him yet, but they were getting close. I understand he’s seriously ill. His mobility’s restricted.

Curtis shakes his head. If Stanley’s still breathing, he says, then NJSP is not as close to him as they think they are. And I highly doubt that he’s still in AC.

Okay. Where do you think he is?

He’s wherever Damon is. And vice versa.

The agent makes a skeptical face. I know it doesn’t make much sense, Curtis says. But that’s how it is with those guys. They’ve got the goods on each other. They’ve got something to settle, and they’re gonna settle it. The question is where.

The guy’s rollerball hasn’t touched his notebook. So your advice on how to find Damon Blackburn, he says, is basically to find Stanley Glass. And vice versa. Have I got that right?

My advice, Curtis says, is that I hope you have better luck than I did. That is pretty much my entire advice.

The agent pulls his tie from his pocket, smoothes it across his breastbone, replaces it with the inkstick. Mister Stone, he says, I should let you know that I am not anywhere close to being done with you. But I do wish you a speedy recovery, and I thank you for your cooperation today.

No problem, Curtis says. Hey, do me a favor, though. I’m starting to hurt pretty bad here. If we’re done for now—

Sure thing, the agent says. I’ll get the nurse.

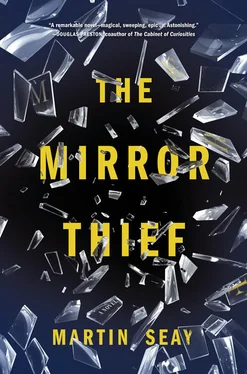

The nurse comes, messes with Curtis’s IV, and soon everything’s flattening out, becoming dull and vague. For a second, he has an answer to the agent’s question — it’s obvious: he pictures The Mirror Thief lying on Veronica’s coffeetable, dropped on the Quicksilver carpet — but then the drug snatches it away, and he lets it go. He wants to quit thinking very soon.

A warm swell of tears fills his half-empty eyes. He waits quietly and thinks of Damon until the medicine finally finds his brain, until he can’t remember anything anymore except the weightless surge of planes taking off — out of Ramstein, out of Philly — until he knows nothing of his own past, until time seems to have stopped and he feels like he is no one at all.

Curtis. Add up the letters of the name, they come to four hundred eighty-two. Autumn leaves , it means. Or, believe it or not, glass . Add those three numbers — four plus eight plus two — you get fourteen. A gift , or a sacrifice. To glitter , or to shine .

Sometime later — minutes or hours, it’s hard to know for sure — a telephone somewhere nearby will start to ring.

When the cops and nurses burst into his room, Curtis won’t even be aware of the sound. He’ll wake grudgingly, blinking at the overhead lights as cops gather: whispering into cellphones, setting up a recorder, stretching the cord of the hospital phone until the base rests next to Curtis on the mattress. He’ll watch their busy mouths as they talk to him, and he’ll nod, although he’ll understand nothing they say. And then, as someone’s finger mashes the phone’s SPEAKER button, he’ll angle his head, and he’ll try to listen.

Somehow he’ll know right away. He’ll hear the ghostly whine and hiss — long distances, strange satellites — and know exactly who’s calling, and from where, and why.

But he’ll ask anyway. He can’t help himself. Stanley? he’ll say. Is that you?

And then, after a long moment, you will answer him.

Good morning, kid, you’ll say. Or good evening I guess it still is, where you are. Been a long goddamn time, hasn’t it? I’m glad to hear your voice.

You won’t keep Curtis long. Not because of the cops — what can cops do to you now? — but because there isn’t much to say. Or there’s too much. Anyway, you’ll keep it simple. You’ll say thank you. Then you’ll say you’re sorry. Then you’ll say goodbye.

Another gust: the hotel window rattles. You hear churchbells ring, the scream of a gull. You draw the blankets tight around your chin.

In another minute or two you’ll get up, make the call. You put the kid in a bad spot, so it’s the least you can do. You should phone Veronica, too, while you’re at it. See if she found what you left her in the airport locker. Her inheritance. That’ll be a tough goddamn conversation. But you guess it ought to be done.

Veronica. Three hundred eighty-eight. A hard stone, like flint, or quartz. To veil. To conceal. To spread out. To be set free.

First things first: you should go to the window. Slide your feet to the slick hotel floor, grip your cane, rise. Somewhere down there — among the fruit- and flower-vendors in the Campo San Cassiano, the bundled old women on the bridge’s dainty steps, the black gondolas that slide down the mucus-gray canal — Damon is hunting you. He must know he’s running out of chances to do this his way: with each passing minute you slip farther from him. So you expect him soon. When he turns up, you want to be ready.

Читать дальше