For some reason, the protestors chose to march along the tram tracks, disrupting traffic. Robby’s grandmother and Madam Marika’s tram was also halted, and several protestors got on, like robbers on postal trains in the Wild West, shouting slogans and ambiguous threats. One of them stopped by the two ladies, looked at them carefully as their breath caught in their chests, and muttered in an ominous tone, “ Yahudi? ”

Robby’s grandmother, by her own account, almost wet her pants with fear. She was speechless. Her face attested louder than a hundred witnesses to her Jewish identity, and, as a result, to her friend’s as well. They were left to pray to the heavens, and they might really have needed a miracle, if not for Renée Marika’s resourcefulness. That very moment she smiled mischievously. “Us? Of course not. We’re Greek, are we not, Kiria Papadopulos?” she said, turning to her pale friend.

“ N é , n é,” answered Grandma in the language of Homer. “Yes, yes.” Then the two went on to converse freely in Greek, until the man shrugged and moved to another car. They continued conversing en grégo even after getting off the train. The two had been fluent in the language ever since their childhoods spent in Balkan territories with shifting borders. Robby’s grandmother was from the town of Dedeagach by the Dardanelles, an area with much experience in the Greco-Turkish War, and later named Alexandroupoli. Renée Marika was born in Rhodes. Greek was her mother tongue, along with Ladino — which we used to call Español —the language of nostalgia, each word giving way to yearning for faraway Spain, with which we’ve had such a tumultuous romance.

That evening the protests died down, and by the time Robby got home no trace was left of them. The protestors did not smash store windows or set tires on fire. True, they screamed at the tops of their lungs, but such screams dissipate in the twilight, when a light breeze blows, allowing throats to breathe freely, fear to diminish and the heart to rejoice.

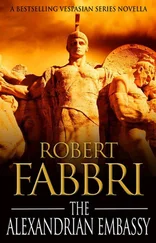

The investigating judge flipped through the dossier dis-interestedly. Hamdi-Ali, Tal’ooni. Suddenly his curiosity was piqued, realizing that Hamdi-Ali was Jewish, in spite of his seemingly Arab name. The investigating judge had no issue with Jews. Many of his friends were Jewish, and he was proud of that. Tal’ooni v. Hamdi-Ali. He didn’t like mixed cases, where animosity between nationalities and religions complicated a conflict between two men. Well, what have we got here? Drugging a horse in an attempt to fix a race and … attempted murder. Attempted murder? Well …

The heat in the dark office was unbearable. An exhausted ceiling fan lazily dragged its blades, its hum putting the investigating judge to sleep. A fly circled his nose. “George!” he called to his Coptic assistant, sitting in the adjacent office in front of piles of paperwork. George returned his pen to its blotter and ran in bowing to hear his supervisor’s wishes.

“ Ahwa ,” said the lawman, swallowing the first letter of the word for coffee, qahwa . In Egypt no one pronounced that heavy q , which might be why Egyptian Arabic always sounded more refined to the European ear.

“ Aywa, ya sidi ,” answered the young clerk, pushing his fez slightly in subordination.

Maybe the coffee would wake him up, the investigating judge thought, and shot George an affectionate, paternal smile. With deep gratitude, the young man bowed his way back out the door. Accompanied by a symphony of typewriters, he walked down the depressing gray hallway. When he reached the young secretary at the end of the passage he saw her putting on makeup in front of a small compact mirror. She spotted him from the corner of her eye and quickly hid her makeup kit, but she’d been caught. George said nothing. His accusing look was more than enough. “The old man wants a coffee,” he said with authority. His mission had been accomplished and he returned to drown in paperwork.

The girl stood up, walked downstairs to the doorman and gave him the order. The doorman looked aggravated, but jumped up immediately. “Khaled! Ya bne’l kalb , you son of a bitch, wake up!” he called out. Khaled, his young son, would be the one to walk the two hundred yards to the nearest café. “ Sukar ziada !” Extra sugar, the doorman ordered. “It’s for the bey,” he added with importance. The bey liked his coffee sweet. To tell the truth, the investigating judge wasn’t really a “bey” at all, but he enjoyed the doorman addressing him as such, and sometimes repaid him with bakshish. Out of sincere gratitude, the doorman continued to use the title even when the judge wasn’t around, and especially when speaking to his son, Khaled. He wanted to make sure the title became engrained in him as well, so he never forgot to use it when in the presence of the great man.

The coffee was brought over by the café owner himself, in peasant pants, a hooked mustache and a jaunty fez. He wouldn’t take the risk of entrusting the high clerk’s coffee to the hands of one of his employees, who, with their pigheadedness, might lose the kaimak. Then the bey might complain that the coffee he sells is nothing but sewer water. Once the coffee was placed in front of the investigating judge, along with a glass of very cold water, the man sighed deeply and said nothing. The café owner immediately asked the reason for this heavy sigh.

“When your father, God have mercy on his soul, ran the café, he always brought along a little shisha , without me having to ask …” He sighed again and added philosophically, “The things we receive without having to ask, those are the things that bring us real pleasure.” And he sighed once more, as if to say, Nobody bothers to uphold standards anymore …

“I’ll send the boy over right away with —”

The clerk fixed his eyes on him, and the café owner hurried to correct himself. “I’ll bring one over myself.”

The clerk smiled and tossed a coin his way.

The coffee and the shisha and the cold water alleviated the judge’s sweaty and sticky summer malaise. Even the limp fan seemed to have regained some of its youthful energy.

Al-Tal’ooni v. Hamdi-Ali.

The horse racing business.

The judge, who was addicted to cards and dice, could not understand why people got so worked up about horse racing.

“ ‘Attempted murder.’ Esh da? What does that mean?”

He read through the investigation report and the charge sheet. He wrote with pencil in the margins, “assault” instead of “attempted murder.” An old man, nearing seventy, against a young man of twenty-five-years. He shook his head. People had nothing better to do these days. The protests worried him quite a bit as well. The police had arrested some of the loudest big-mouths of the mob, but deep inside he knew that something was cooking in the outskirts, something was bubbling beneath the surface. I can feel it in the soles of my feet, he thought, and when it erupts, no one will be safe. Not even His Majesty, the King. Especially not the king. He set his eyes on the portrait of the young, auspicious Prince Farouk, handsome, smiling Farouk, the way he looked on that hopeful day when he disembarked from the ship that returned him from England to Egypt upon the death of his father, King Fouad. Now Farouk was fat and corrupt. Will they use a guillotine, like in France? A gun in the basement, à la russe ? And he, a rather lowly investigating judge — will he be considered small fry, someone not worthy of consideration, or will he earn the honor of being named Enemy of the People, a term so favored by revolutionaries the world over? Why can’t things just remain as they were?

Читать дальше