“He must have been an angel,” Madame Marika couldn’t resist, but Robby’s aunt was in her own world, staring out beyond her friends’ ridiculing smiles. Her gaze clung to the small, green, alert eyes of her sister, Robby’s grandmother. Her sister had also become a widow in the same year, 1948. Three years had gone by, the eastern winds kept blowing and their pain was slightly dulled.

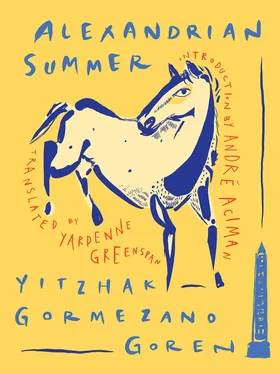

The story of this unfortunate woman, who, years later, when she died in Israel, was described as not having known a moment of peace her entire life (which is a slight exaggeration), the story of this widow and her three daughters and one son, Raphael, is one of those Alexandrian stories that deserves to be told, and maybe it shall be, but our story is about the Hamdi-Alis, a family from Cairo that came to spend a summer of joy on the shores of Alex; Aunt Tovula’s story must wait, along with others, for its proper time.

The conversation is back on course: “What can I tell you, good women, if you haven’t heard Joseph curse in Arabic and Turkish, you haven’t heard proper cursing in your life!”

“And all because Emilie dared suggest he go see a doctor?”

“As I live and breathe.”

“And how did she react?”

“Locked herself in her room and cried and cried.”

The women sighed. Crying, tears, that was the only outlet for women in this world of men.

“In Arabic and Turkish!”

A riddle floated through the air: What’s going on with Joseph? His response was in no way proportionate to the scale of the catastrophe. It was clear that a much deeper crisis was taking over the old man. Something that touched his essence, his flesh, and was beyond winning or losing a race at the Alexandria Sporting Club. But who could think hard enough to figure it out in this heat and this dry air …

“Salem, salim idak !” Marika burst out with joy. “Bless your hands, Salem!” The servant walked in carrying a large tray with glasses of cold water and a plate of jam, snow-white and sweeter than honey, the kind Grandma called dulce blanco . Each woman enjoyed a spoonful of jam and a sip of refreshing water. Emilie and Joseph and the echoes of their drama melted away in all the chewing and gulping.

The only member of the Hamdi-Alis who continued with the normal course of life was Victor. No one thought of him or bothered him, everyone was preoccupied with David and his fateful race next Sunday. The marbles formed tracks through the rug. Sometimes they tapped one another, other times they overtook one another, working with a kind of secret regularity known only to them. In the dark coolness of the hall, the heat wave seemed faraway and unreal. The game went on, like a kind of ceremony, in almost complete silence. Suddenly Robby told Victor, “Your father … why is he taking this whole thing so hard?”

Victor looked at him for a moment, as if incredulous that Robby would stop the game so abruptly only to ask such a silly question. Robby had to repeat the question before receiving an answer. “Why? Because he’s stupid.” Victor went back to the game and scored a nice point from a distance, while he remained standing up. He dropped Robby’s marble in his pocket and waited for Robby to fulfill his part of the ritual and place another marble on the rug.

But Robby only looked at him with wonder. How could a son speak of his father this way without being struck by lightning? “How can you talk about your father that way?” he asked, appalled.

“He’s stupid, I tell you.” Victor saw things plainly, and did not realize that his friend still lived in a world in which parents were beyond all judgment. “He’s forgetting that racing is only a game. Just like marbles. Who gets sick over a stupid game? Only fools! Put a new marble on the rug. Go on!”

Robby fished a new marble from the depths of his pocket, looked at it in a heartbreaking goodbye, and placed it down instead of the one that had been taken from him. The game went on.

Suddenly, they began shouting:

“Cheater! I saw you!”

“You saw me ? And what exactly did I do to deserve being called a cheater?”

“You didn’t toss it from your spot. You took a whole step forward, and then you scored a point. That doesn’t count!”

“You don’t know how to lose with dignity. You should learn from the English!”

“You and the English can kiss my ass!”

“Just say it, did I score that point or not?”

“You did, but you cheated!”

“I either scored or I didn’t, that’s all that matters. This marble is mine !”

“You won’t get it, even if you stand on your head all the way to tomorrow!”

And the two wrestled on the rug, pounding each other with their fists.

They’d never fought with such rage and hatred before, and all over a silly game of marbles.

Two days later, the heat wave dissipated. It left as suddenly as it came, and while Alexandria savored the cool breeze, its short-term memory quickly forgot the five horrid days of heat. Once more, city-folk would argue that heat waves never hit Alexandria, that eastern winds only blow through boiling, dusty Cairo …

Peace also overtook Joseph’s face. He sat on the balcony, eyes almost closed, the wind rising from the sea caressing his square, gray mustache. He sipped his black coffee, his lips smacking with pleasure in a manner uncommon around these parts. It was clear that some sudden change had occurred in Joseph, as if all entanglements had been undone at once, and all crises evaporated as in a bad dream. At first he remained silent, but even the few sentences he spoke sounded a newfound, rather odd optimism. In all honesty, the majority of those dwelling in the apartment did not notice this change at first, and those who had did not imbue it with much significance. If it hadn’t been for the events that began that day, it might have gone unnoticed. Only afterward did various wise parties begin boasting about how they foretold it all, stating, “Indeed, I could tell there was something strange about him.”

Even Emilie did not see a reason to worry. Perhaps, she in particular did not. She was a natural-born optimist unable to view a positive change as an ominous sign. She was relieved and thanked God for His benevolence.

That night, in bed, she even dared snuggle up against him, feeling his body cast confidence and serenity over her, and smelling his tobacco. He caressed her softly and whispered words of love in Turkish, the language of their youth, of their intimacy, the language he spoke to Leila.

She told him how much she wanted a grandchild, and he laughed slowly.

“Why are you laughing at me, Yusef?” she asked indulgingly, choosing the eastern Turkish version of his name. It was that voice and that “Yusef” that stole his heart thirty years ago, when she was seventeen and he was thirty. That voice hadn’t changed. Close your eyes and you can hear that “Yusef” being spoken by that seventeen-year-old girl, light in her eyes and music in her voice. And suddenly that girl, whose breasts had only just emerged with the force of adolescence, is talking about a grandchild, a grandchild. “Why are you laughing at me, Yusef!” she insisted, resting her head on his chest.

“I’m not laughing at you,” he said quietly, almost inaudibly. They used to say about Joseph Hamdi-Ali that even when he spoke he was actually silent. Then he raised his voice and said, “I respect you and I love you. You are my bella donna . I left my family and my tradition and my homeland for you. You are my family, you are my tradition, you are my homeland.”

Emilie accepted these words with simple joy. Pathos is at home in the East, never sparking ridicule or embarrassment in anyone but the fastidious. She accepted his words with neither pride nor guilt, as self-evident. She did not hold herself responsible for being a man’s entire world and foundation. Another woman would have been filled with purpose and begun playing a role beyond her means. Emilie never thought her husband’s words were intended to place some special mission upon her shoulders. Even during this crisis, her support and help came through her silence and calm, her generous expressions of love, without a word of guidance or advice. Emilie did not sense that her husband was calling to her from the depths. She did not perceive this seeming calm that had descended upon him as even more dangerous than the storms that preceded it. She didn’t understand that when he said, “You are my family, you are my tradition, you are my homeland,” he was merely repeating his words from the past, which were now empty, devoid of truth. Perhaps even Joseph did not know he was deceiving himself, with the fantasies he projected on the pure, white body of a seventeen-year-old. Her voice was soft and cheerful, her skin sweeter than Turkish delight. But a bird on your win-dowsill will sing softly and cheerfully, and yet you would not hang all of your hopes and dreams upon her … A slight tremble ran through his bones and he asked her whether the window was open.

Читать дальше