“A prostitute is a woman who screws for money.”

“People pay for it?”

“You bet.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“You don’t believe me. Fine, don’t believe me. But there are houses like that, there are. You go there, walk in, pay, then they put you in a room where a woman waits for you, totally naked. You take your clothes off and screw her. After you finish, you pay and leave. It’s simple.”

Robby looked back at the two men walking away. “What! You mean to tell me that your father is taking your brother to a woman like that?”

“Shh … the whole house will hear you.”

“It can’t be!”

“You’re an idiot. What do you know, anyway? You’re a baby.” He turned his back on him with ridicule.

A father taking his son to a prostitute. Would his father also come to him one day and say, “Robby, let’s go,” then take him by the hand to a big, dark house? What do those houses look like? Maybe they’re more like palaces? Rooms upon rooms, like cells in a beehive. In each cell, a naked woman. His father would motion and say, “Choose, son, the world is your oyster,” twisting his face with a small, lusty smile. The whole world is gaping, pink genitalia. He wouldn’t know what to do. His eyes would cling to his father for help. Once he almost drowned in a whirlpool in the capricious sea, in the Agami neighborhood, and thought his end was nigh, but then he felt his father’s arm grab him, ripping him away from the water’s death grip. This time, however, his father would not come to his aid. On the contrary, he’d say, “That’s it, from here on out, you’re on your own.” On his own in a small, seedy room with cobwebs and … a woman. A big, writhing woman, a womb of quicksand …

“But … why?”

Victor smiled and hugged him almost paternally. “So that he can let go of all that tension. So he can be light for his race, and win.”

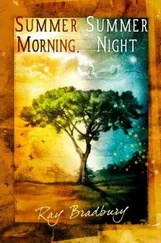

A simple, satisfying explanation. Emotional pressure. Stress and nervousness before his race. A bit of entertainment (apparently, going to a prostitute is somewhat entertaining) can help release such tensions. Robby never imagined that such a release could be a basic, simple, physiological process, just like squeezing toothpaste out of the tube, and inquired no further. Not that he had all the answers now, but the serenity of the afternoon made him feel languid and sleepy. The sun sprawled out among the clouds, like a giant orange on a pile of white blankets. A light breeze caressed tired eyelids.

At the Café de la Paix, old men and women in summer garb began taking over the round white tables scattered over the sidewalk, their large, colorful sun umbrellas unable to protect the diners from the warm, diagonal rays. The elderly breathe in the wind and, with half-shut eyes, sip their Turkish coffee with creamy brown kaimak on top. Among them is a young couple, their faces tan and their arms bare, a floral dress with a cheeky neckline. A throaty voice bubbles up, like the cooing of pigeons in love. An Arab selling jasmine wreaths enters. Multiple flower necklaces hang from his neck and arms, and he pushes a reed cart full of them. From the height of the second floor, Robby becomes intoxicated with the aroma of flowers, or maybe it is his imagination, not his nose, that enjoys the scent. The young man buys some wreaths and wraps them around his girl’s neck. She laughs, her bouncing chest spraying off shreds of flowers, and the white of the jasmine sprays like sea foam over tanned curves. Waves of perfume rise again with a light wind. The breath is calm. The eyes close.

David sat slightly apart from the rest. From within the cloud of heavy smoke, illuminated by the red lights of the club, his father’s fez appeared again, red hot, like the floating barrel that bobbed among the waves at Sporting Beach. At his side were several other fezzes — the old men spoke emphatically, their faces businesslike and their wrinkles vibrating. With dreamy, covetous eyes, David watched the frantic curves of the dancer Shakra Roomy. Her twitching navel hypnotized him into intoxication. Her protesting breasts, demanding to remove the burden of the golden brassiere, decorated with glass necklaces and jingling coins, also swirled in circles through the air, and in a moment of delusion he imagined them rubbing his burning face. The raki , that Turkish anise spirit, diluted with a drop of water, created hot steam inside his head, thickening clouds of fog before him, and through it all, the sounds of rhythmic eastern music, going round and round in endless cadence … In his blurry mind, David wondered if the girl had a price. He was once told that every woman had a price, but, in his natural decency, refused to believe it. Women like his mother, for instance, could not be bought. Suddenly it occurred to him that women like Robby’s sister could not be bought either, and the thought sobered him, like a broom sweeping away the cobwebs of merciful drunkenness. He quickly brushed the thought away and returned to his expedition around Shakra Roomy’s jiggling belly.

Shakra wasn’t an Arab. Her parents had migrated to Alexandria from the Balkans, possibly in the same period that Joseph and Emilie Hamdi-Ali and Robby’s parents arrived as well. David once read a book, perhaps by the great Flaubert, a travel book about 19 thcentury Egypt, in which Turkish belly dancers, who in Egypt served as high-end prostitutes, shaved the pubic hair off their romantic triangle. The thought sent a tremble of lust through him. A woman, white from head to toe (in his excitement he forgot the brownish-pink halos around her nipples), a little girl, blown-up. He’d often seen little girls in the nude. In his virginal imagination, he tried to illustrate this metamorphosis, but he couldn’t conjure up a clear image of a shaved woman, which served only to further ignite his elusive lust. This Shakra must also have a price. Distractedly, he rummaged through his pockets, feeling some bills and coins. Had his father not been with him, he would have tried to discuss a more intimate meeting with her. He looked at his father, and though the latter was conversing with the other men and paying no attention to his son’s endeavors, David blushed and curled up in his corner.

“Hamdi-Ali, ya omri , my soul!” one fat Armenian in a fez tried sweet-talking Joseph. “ Ya Hamdi-Ali, my brother, who knows better than you that the God above gives only one chance, whether you’re a wise man or a fool, you only get one. The wise man jumps at it, grabbing it like … like a woman’s breasts. While the fool …” He waved the thought away.

Joseph said nothing. His eyes were dark and stubborn. Once in a while, he glanced at his son, glad that David wasn’t listening to this shameful conversation he was forced to have with his friends. His friends! One trainer and two bookies. The trainer, his old Greek friend, Panayotti Helikos, who’d been Ahmed Al-Tal’ooni’s trainer and business manager for a long time. He was a small man, with a shiny black mane and a hooked mustache that looked as if it were painted over his thin top lip with pencil liner. He spoke with exhausting speed, switching languages to create a mélange of Turkish, Greek, French and Arabic, with a few English words to spice things up. With his will of steel, he’d decided to turn his employer into a champion, no matter what, even recruiting the support of the two craftiest bookmakers in Alexandria, the Armenian twins, Toto and Sisso Georgian.

How dire, that Joseph was forced to sit here, at his age, with his flawless reputation, like a city under siege, suffocated with smoke, attacked from all directions. He wanted to go out to the night air, stand by himself, lean beneath the yellow glow of a streetlamp and smoke his cigarette quietly, his cigarette alone, inhaling only its smoke, without the nauseating mixture of smoke and hot breath, turning the air inside the club into an unbearable mush. The repetitive rhythmic music, looping endlessly, pounded inside his head like a stubborn hammer.

Читать дальше