Seeing that this was a lost cause, Victor suggested going to his own parents’ bedroom, emphasizing the proposition with a gallant gesture, to signal how much more generous than Robby he was. Claude ran ahead with excitement toward those soft pillows, and Robby could hear the springs of the mattress protesting as he landed.

When the brothers, Isaac and Maxie Ephraim, showed up, the three boys didn’t even bother to get dressed and pretend to play marbles. The two new arrivals undressed with haste and joined in the fun, as though this had always been their favorite game.

After the kids left for their homes, Robby and Victor stood on the balcony and watched the red sun, reclining, heavy and dreamy, among soft pillowy clouds. A light breeze rose from the sea, caressing their flushed cheeks. They were united by their new secret, and Robby felt a kind of affection toward Victor. It was a nice game. A boys’ game. The grownups were enjoying the race that was closed to children, but the children had their own little secret, they had a place where no grownups were allowed.

“I hope he loses,” Robby heard Victor whisper.

“Who?”

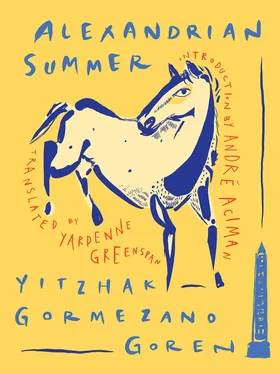

“I hope he falls off his horse.” Victor’s voice trembled. “Just once. Have him break an arm or a leg. Not die, but have something happen to him.” Then he kneeled, put his hands together and mumbled, “Dear Lord, please let something happen to him.” This devil, kneeling like a Christian, saying a prayer to the God of Jews. “If you do this for me, I promise I …”

But Robby didn’t hear Victor’s vow. He remembered Marcelino, a pale Italian boy who lived around the corner, right over Hamis’s store. Marcelino had been sickly since birth. When Alexandria was plagued with cholera, he was at death’s door. The doctors gave up and told his parents that only a miracle could save him. His mother took this literally and went to the church in the Ibrahamiya neighborhood, confessed her sins and prayed to Saint Anthony, vowing that if he spared her boy she’d devote his life to the church and change his name to Sant’Antonio. God made His choice, and perhaps the saint lent a hand too, and Marcelino healed. With Neapolitan vigor, his mother prepared to keep her promise. A deal is a deal. Since then, on Rue Delta, one might come across a skinny little boy wearing a heavy brown monk’s cassock, the rope tied around his waist dangling lower than his ankles, gaily sweeping the sidewalk like a child dressed for carnival. Sant’Antonio!

Dusk already clutched the corners of buildings and began slowly hovering down and piling on the street. Suddenly, as if born from darkness itself, the lamp lighter appeared at the end of the alley on his bicycle, holding a long magic wand, at its tip a single small and stubborn flame which he used to light the gas lamps along the sidewalk. He didn’t even get off his bike, but instead pedaled his way from lamp to lamp, naively believing that at the same time God was riding his heavenly bike in much the same fashion, lighting the stars in the sky. And indeed, the stars appeared one by one, their light yellow. The entire street was now dipped in a magical aura. It was the aura of Sant’Antonio, who would never again play marbles or hide-and-seek, his life now dedicated to prayer and study.

This untroubled street, which not an hour ago was bathed in sunlight, its head dipped in water, was now gripped by chills, and it hurried to wrap itself in a navy-blue sailor’s coat with silver buttons. There, in the heart of the bluish silence of twilight, was a loud, bright spot of light. A group of people wearing white, a cheerful ruckus coming from the center of their circle. The spot of light disappeared into the fabric of dark blue velvet, and then lit up again under another streetlamp. Only the buzzing did not fade away, but rather grew stronger, morphing into roaring laughter, the laughter of joviality.

Victor looked at the light and knew. His prayers had not been answered.

David Hamdi-Ali had scored a sweeping victory over his racing opponent.

From twenty years away, beyond lands, seas, oceans, exiles … as an archeologist wandering in the darkness of oblivion, carrying the flashlight of memory that lights small corners here and there: an ancient mural dolled up in red, yellow and gold; a fresco that had once known the blessing of sunlight; the diagonal rays of Aten, god of the sun, ending in tiny hands, giving the grace of sun to the head of the pharaoh and the head of his adored Queen Nefertiti.

Robby dances his Nefertiti dance. Only Aten himself knows how this bashful boy found the courage to improvise an ancient Egyptian dance. Thérèse, at the piano, messes up Samson and Delilah as best she can, and only Marcel the musician wrinkles his face at a tuneless note that no one but him notices. Victor’s disdainful eyes do not break the ceremonial serenity of Robby’s angular motions. Only one small worry trembles in his heart, but he does not show it: the overturned bucket, the fact that it might once more fall on his nose, which is protected with a pink bandage. But the bucket cooperates and stays put.

The dance went off without a hitch. Well, almost without a hitch: in the middle of the show, while Robby was certain that his audience was mesmerized, old Aunt Tovula sighed and said, “ Pisharé !” meaning, “time to pee,” and even stood up to carry out her plans. This innocent comment raised thunderous laughter that blurred the impression made by the show. Seeing what she had done, she sat back down with a teasing grudge. “ Qué hay? Ma qué ténéche ?” she asked with protest. “What’s wrong? What’s wrong with you?” Then her face softened and she turned to Robby’s mother for some affection: “ Qué diché ? What did I say?” Several voices joined together to hush the old lady and Robby bit his lips, but knew that the show had to go on, and decided to ignore the incident. Slowly, the tumult died down and the dance continued. Once it was over, laughter broke out again at the sight of the poor old aunt running urgently toward the bathroom. Now even Robby allowed himself a small smile. Aunt Tovula was his favorite, and he couldn’t stay mad at her.

Somebody started to clap and the rest followed. Thus, the honor of the dance was restored. Robby’s face grew serious again immediately. A light bow, the lightest, the Queen of Egypt wouldn’t bow very deeply, let alone with this bucket atop her head, which might fall to the ground in a metallic clatter.

Thérèse used this opportunity to give Robby a suffocating, pre-maternal hug, until his head was pressed between the evil hardness of the bucket and the generous softness of her ripening breasts. Now that he’d tasted the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, fed to him by Victor, he could no longer lean his head against this feminine tenderness without blushing and pulling away a little. The grownups laughed. Juliette wanted to hug him as well, but he wasn’t there anymore. In a flash, he was in the back room, at the end of the hall, explaining that he had to change. He didn’t turn on the light. It felt urgent to get out of these ridiculous women’s clothes. Had he actually been good, or were they just making fun of him? He was mad at himself for not being able to let go of these maddening thoughts. Why can’t he do anything simply and fully without pointless pondering? He stood in his underwear, looking out the window. The moonlight painted his body silver, and cool, damp air touched him in a light, pleasurable caress. The window across the street was dark — Dora and Louis Abarbanell were among the audience at his performance. He loved small, delicate, fragile Louis, torn between his love for his big, sad mother, and his yearning for his father, small and fragile like him. Every Sunday morning his father picked him up for a walk on the boardwalk, where he treated him to black, sticky licorice. Louis hated licorice, but never dared tell his father, so as not to hurt him. Once, Robby asked to join them on their walk, but Louis forbade it with burning zealotry. A child like Robby, growing up in a harmonious household, could never understand such a strong response.

Читать дальше