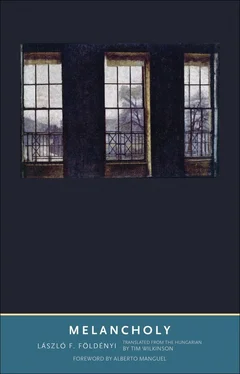

The derivation of melancholia from original sin placed the illness in a new light. It extended to everyone; the sadness, the desperation, the thrownness ( Geworfenheit ), and the desire to be elsewhere were transformed into a normal state of being, a condition that has been impossible to rectify since man has existed. The state of being human is “incurable”; the deep chasm between a person’s createdness and grace is unbridgeable. In parallel with the medieval notion of melancholia, following the turn of the first millennium the view became ever more common that if inner conflict and self-alienation were common states of existence, shared by all of us, then they ought to be “made use of.” It did not matter whether this would be against God or to his glory; all that was important was that the torrent of doubt that estranges people both from God and from themselves should gain legitimacy. This judgment of melancholia in itself was medieval: the daring view had not yet been born that melancholia not only provided an opportunity for an alternative take on existence but was also just as autonomous, self-supporting, and therefore unassailable as the well-known “ordinary” way of looking at things. Although in relation to ecstasy St. Bonaventure writes of “a divine melancholy” and “a spiritual wing” (Burton, Anatomy , partition 3, sec. 4, member 1, subsec. 2, 343), which proves that he is far from regarding melancholia as just a mental sickness. But in general the era still spoke of melancholia disapprovingly, which is why he thought of ecstasy differently from the Greeks: he saw it not as a “stepping out of” but as a “stepping into” the Christian realm. The story of Jesus, no less, justifies this view. Jesus’s disciples in Capernaum considered him deranged because he stepped out of (that is, neglected) a regular style of living. 6In Jesus’s case, stepping out of or standing beside himself (ecstasy) meant at one and the same time stepping out of the earthly realm, which is to say, stepping into God’s kingdom. Bonaventure’s “ecstatic melancholia” is good only insofar as it diverts attention from worldly vanities: if it encourages that, then it is a testimony to God’s love. 7If the Aristotelian scheme of melancholia ever cropped up, it was interpreted also in that spirit toward the end of the Middle Ages. It was first mentioned by Alexander Neckam around 1200 and not much later by Albertus Magnus, but both of them took the edge off the original concept. William of Auvergne, the thirteenth-century bishop of Paris, likewise made reference to Aristotle, but reinterpreted him in a Christian manner: melancholia liberated people from sins of the body and enlightened them: “This complexion withdraws men from bodily pleasures and worldly turmoil. Nevertheless, though nature affords these aids to illumination and revelation, they are achieved far more abundantly through the grace of the Creator, integrity of living, and holiness and purity” (quoted in Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy , 73). Melancholy was a form of asceticism, and William saw it as a desirable state exclusively in that sense: he had heard about many pious men whose “most fervent wish was to be afflicted by melancholia, since that surely strengthened spiritual goods” (quoted in Günther Bandmann, Melancholie und Musik. Ikonographische Studien , 104).

This conception of melancholy remained within the bounds of the Christian interpretation of existence. That positive perception nevertheless represented a kind of countercurrent against the prevailing view. With the appearance of St. Francis in the thirteenth century, the rigid separation of nature from spirit came to an end; all phenomena of existence became equally important, and this was evident not only for ordinary all-embracing faith but also for the sensual take on the world. Sensual diversity (that is, the profusion of the world) did not preclude divine unity; and the focus on the individual, which had started to gain ground in Europe, signaled the cracking of a closed system of beliefs. Antiquity’s interpretation of melancholia obviously found a breeding ground in between those cracks. If the Middle Ages began to regard melancholia as a disease of the mind, then in the last analysis it managed to hide the cracks, but when melancholia was analyzed as a positive state of being, the cracks were not hidden from posterity’s gaze but were in fact made more visible. If melancholia is regarded as an illness, then it will be seen as dangerous by society, and for that reason — and there are plenty of examples of this in more recent history — it will be invested with collateral political significance. Melancholics themselves, however, do not in the least think of themselves as being either ill or subversive. Their mournfulness and despair relate not to one or another, possibly adjustable or rectifiable, form or manifestation of human contact or institution, but to existence in general, and therefore they are not pinning their hopes on any remedy. A judgment of melancholia hinges on whether one tries to put oneself in the shoes of a melancholic or treats him purely as an object. One has the impression that toward the close of the Middle Ages an ever-increasing number of people strove to recognize the legitimacy of the melancholic interpretation of existence — but for that to happen, the whole culture had to move. The revival of Hellenistic astrological explanations for melancholia laid the groundwork for that earthquake.

Notions formed about “children of the planets,” indeed, the science of astrology in general, were revived from the eleventh to twelfth centuries onward. Through Arab stargazers (Abu Ma’shar and Ibn Ezra), a gradually spreading antique Hellenistic astrology aimed to find a correspondence between individual diversity and the unity of the world. The Greeks adopted from the Orient the idea that there was a parallel between the human body and the universe (the body of the cosmos); the two kinds of medical schools of thought — the Hippocratic and the Empedoclean — likewise grew out of these; indeed, in the sixth century BCE, Alcmaeon of Croton, often referred to as a pupil of Pythagoras, anticipated Plato in discerning a connection between the constant movement of the stars and the immortality of the soul. (Pythagoras is said to have called the planets the dogs of Proserpine; see Jaap Mansfeld, Die Vorsokratiker: Auswahl der Fragmente , 1:191.) The late Middle Ages revived that doctrine, and the astrological approach began to gain ground within the field of medical science. Paracelsus was of the opinion “that a physician without the knowledge of stars can neither understand the cause or cure of any disease, either of this [melancholia] or gout, not so much as toothache” (quoted in Burton, Anatomy , partition 1, sec. 2, member 1, subsec. 4, 206). According to Melanchthon “this variety of melancholy symptoms proceeds from the stars” (ibid.). In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an external cause was always sought in relation to the mind, and mental illnesses (for example, melancholia) were attributed to supernatural forces, and above all to an influence of the stars. 8The derivation of melancholia from the position of the stars set it in a new light in opposition to the theological interpretation of the Middle Ages. Anyone who was melancholic was under the sway of Saturn — his condition was therefore not a matter of choice , a consequence of rejecting grace or shutting himself down, but of fate, against which one could only fight, at best, with the help of other planets. The closedness of a cosmos made up of seven planets was not the same as the power of divine omnipotence to close up everything (which was why Christianity persecuted astrology at various points in history), so the Christian perception of the Hellenistic era had to provide the planets with a Christian-ethical interpretation in order to fit astrology into its worldview. 9In the Christian view, the planets, too, were moved by God and were thereby deprived of their omnipotence: “This Mind. . was fashioned by the seven Governors [that is, the spirits of the planets], who encompass within their orbits the world perceived by the senses. Their government is called destiny,” one reads in “Pœmandres,” an early Christian Hermetic dialogue. Boethius, in the Consolation of Philosophy , wrote: “Providence embraces all things, however different, however infinite; fate sets in motion separately individual things, and assigns to them severally their position, form, and time. . So the unfolding of this temporal order unified into the foreview of the Divine mind is providence, while the same unity broken up and unfolded in time is fate” (bk. 4, 6). According to the Gnostics, a soul, on descending to Earth, comes ever closer to the material world and, resting every now and then in the circles of the seven planets (that is, the seven low-lying spirits), acquires ever-newer material (that is, bad) attributes (the way the seven Christian cardinal sins appear in “Pœmandres” is that in the soul’s fight with the spheres, the higher she rises, the more she sheds her sins). For Christian Neoplatonists, by contrast, the higher the planets raised a soul toward God, the more good properties (the seven virtues) they could bestow on her. For both approaches, the seven planets were tools with which God renders earthly souls material . Their role is nevertheless ambiguous: they are characterized by polarity and ambivalence. This manifests itself most spectacularly in the case of the seventh and most distant planet: according to the author of “Pœmandres,” the soul in the seventh zone divests herself of “the malicious lie” (25) or, according to other Gnostics, the sin of dolefulness, idleness, and stupidity. According to Plotinus, however, the seventh planet ensures a person’s intellect (  ) (see Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy , 153); in his commentary to Somnium Scipionis , on the other hand, Macrobius endowed the seventh planet with the capabilities of logic and theory (

) (see Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy , 153); in his commentary to Somnium Scipionis , on the other hand, Macrobius endowed the seventh planet with the capabilities of logic and theory (  and

and  , ibid.).

, ibid.).

Читать дальше

) (see Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy , 153); in his commentary to Somnium Scipionis , on the other hand, Macrobius endowed the seventh planet with the capabilities of logic and theory (

) (see Klibansky, Panofsky, and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy , 153); in his commentary to Somnium Scipionis , on the other hand, Macrobius endowed the seventh planet with the capabilities of logic and theory (  and

and  , ibid.).

, ibid.).