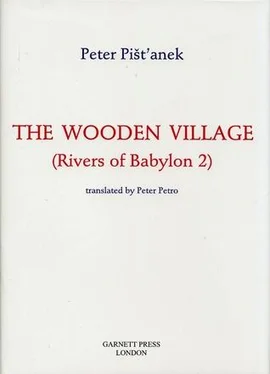

Peter Pišťanek - The Wooden Village

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Pišťanek - The Wooden Village» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Garnett Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Wooden Village

- Автор:

- Издательство:Garnett Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Wooden Village: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Wooden Village»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Wooden Village — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Wooden Village», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Yes, very interesting,” Edna agreed.

Junec mended the fridge, finished his mineral water, deliberately undercharged her, and said good-bye.

Less than a week later she rang again. Her doorbell was broken.

Martin came and knocked at the door. Dressed in shorts, wearing her reading glasses and holding a book in her hand, she opened it.

“Come in, Martin,” she said and let him in.

“Hello, Dr Gershwitz,” Martin said.

“Where’s your colleague?” Edna asked.

“He’s busy doing something else,” said Martin.

Žofré was probably sleeping off a hangover, or working up a new one.

The doorbell had obviously been broken on purpose. Somebody had taken the screws out and disconnected the bell. Martin pretended not to notice. He reconnected the bell and asked Edna to try it. It was all in working order. He got off the ladder and smiled at Edna. Only now did he realise that she reminded him of an American singer and actress, the one with the big nose. His group used to play a song of hers.

“I have another problem here,” Dr Gershwitz said. “Maybe you’ll be able to solve it.”

She took him to her bedroom and pulled out of her bedside table drawer a rubber object whose shape and realistic finish made it look like a man’s penis. Martin had never seen anything like this before, except perhaps in pornographic magazines, and he’d never paid any attention to them. Again, he felt himself blushing.

“It doesn’t work,” Dr Gershwitz said, as she placed it in his hand. “The motor’s broken,” she added. “Could you mend it?”

Martin’s mouth went dry. He knew this was the moment. Clearly, he had got himself into a situation that was neither natural nor spontaneous. Someone had scripted his part and he was supposed to act it, though he didn’t know the script properly.

He hadn’t slept with anyone ever since he had come to the United States, either because he was too shy, or because he had no time. He worked twenty, twenty-two hours a day, every day, weekend or no weekend. He wanted to get ahead. Thanks to his efforts, three years after his arrival in eighty-six, he was working for himself.

“Why do you use a machine?” he asked Edna in a trembling voice, as if reciting a line he had learnt. He knew there was no going back. “A machine can’t embrace you,” he said and showed her. “A machine will never take you and put you on the bed like this,” he said and showed her what he meant. “A machine will never lay you in bed like this,” he continued. With one knee he kneeled on the bed, between her spread thighs. “Do you think a machine can take your clothes off?” he asked Edna, as buttons flew off her blouse in all directions. When he saw Dr Gershwitz’s naked breasts, he started taking deep breaths and wrestled with the zipper of his yellow electrician’s overalls.

“Take this and put it on,” said Edna in a broken voice, handing him a condom fished out from under the mattress.

Martin Junec obeyed and put the condom on his painfully engorged penis.

Dr Gershwitz had also spent a long time without a man and both came the moment their sexual organs made contact. A spark flashed from one to the other and Martin’s condom filled with hot white liquid that he had probably brought from Czechoslovakia.

They lay for a while on top of each other, catching their breath.

Edna recovered first.

“That feels good after a long wait,” she said with a smile, took the rest of her clothes off and threw them onto the floor by the bed. Then, naked, she collapsed by Martin’s side.

“What’s going to happen to us?” Junec asked as world-weariness and a shattering melancholy took hold of him.

“What do you mean?” asked Edna.

“Well, what now?” Martin repeated his question. “What are we going to do now? How do you imagine it will continue?”

“First of all, we’ll wait a bit,” said Edna. “And then we’ll do it again. But this time will do it so we get something out of it.”

“And then?” Martin asked. “What happens next?”

“Then we’ll see,” Edna said. “We’ll sort something out.”

* * *

In 1980 Hruškovič returned from Norway alone. For a while he lounged about spending the money he’d made and visiting the Secret Police, who could not understand why two thirds of the Hurytan trio had asked for political asylum but the third man in the trio had come back. They seemed more puzzled by his return than by the others’ defection.

When the money ran out, he got a new group together with young musicians, and, using the old name, Hurytan, he began to play at dances and gigs in the Ambassador’s night bar. The young bar musicians didn’t stay with Hruškovič for long: for some unfathomable reason he was not allowed out of the country and so the young musicians, who considered playing in the West a pay-off for slavery in the bars, left him. Hruškovič was constantly replacing musicians in the group, since he had no skills except playing music.

One of the musicians who strummed with Hruškovič had major problems with his back. When his back was out, he couldn’t play. Several times Hruškovič got him to lie down in the dressing room and relieved him of his pain with one powerful touch of his hand.

“You’ve got golden hands,” the musician was ecstatic, getting off the table and buttoning up his shirt. “You’re in the wrong profession.”

This was around 1987–1988, when the hysteria around the Russian psychic healer Anatoli Kashpirovsky started. A cassette of his performances was passed round the musicians. Everybody swore that the man was a healer. The base guitar player’s daughter claimed her warts had vanished, the drummer’s chronic cold in the head disappeared, and he no longer polluted his surroundings with it.

“You see,” Hruškovič’s guitar-playing back sufferer said, “You could do the same. Of course, you can make a living playing music, but if you switched to being a healer, you’d be rich. You have the ability; I can feel it in my own skin, I mean, my spine…”

Hruškovič shrugged the idea off, but didn’t stop thinking about it.

Then came November 1989 and the Velvet Revolution. After the New Year, Hruškovič visited numerous healers whose clinics sprang up like mushrooms after rain. Using imaginary ailments as a pretext, he tried different therapies, took advice, bought various teas, magnetic bracelets, dowsing rods and talismans. Now he knew how to start.

Hruškovič lived in the centre of Nová Ves called The Village, just opposite a former pub, Vašíček’s . His house had an outside kitchen, used in summer. One day he cleared it of all the junk, painted it, put down carpets and furnished it like a doctor’s surgery. In the middle stood an enormous massage table that he ordered from the local cabinet-maker Zielinski. Along the walls stood shelves and cabinets filled with mysterious objects, bottles and tiny glass phials filled with various healing tinctures (mostly ordinary water tinted with aniline dye). People were also intrigued by the sight of the spines of old books that nobody read: they were mere decoration. To a casual observer, Hruškovič’s surgery seemed trustworthy and responsible.

In the beginning, Hruškovič decided to see patients only at weekends — he wanted to keep playing with his group in the Ambassador. On Friday, an advertisement was published in the evening paper: Hruškovič offered his healing and psychic services (Hruškovič discovered the term “psychic” in a newspaper article and took a liking to it). On Saturday morning, with his wife’s help, Hruškovič donned a brand-new white coat, hung round his neck a metal cross he bought in a sacral objects shop for 150 crowns, and started on his career as a healer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Wooden Village»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Wooden Village» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Wooden Village» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.