“Remember,” protested al-Baqli, “that I’m in my seventies and have no one to inherit from me.”

“Even so!”

“The great thing is for us to make a start,” said the lawyer.

When they got together in the evening, Isam al-Baqli had a new look and a new suit. But while the filth had vanished, the signs of the wretchedness of old age and former misery still remained.

“Valentino himself, by the Lord of the Kaaba!” said the lawyer, laughing.

As Othman al-Qulla was on friendly terms and had business with the manager of the Nile Hotel, he rented a fine room there for al-Baqli, and the latter at once invited his two friends to dinner. They had a few drinks before the meal and then sat together after eating, planning a meeting for the following day. Then al-Baqli accompanied them to Mr. Nuh’s car but did not return to the hotel. Instead he took a taxi to Mohammed Ali Street and made straight for a restaurant famous for its Egyptian cooking. He did not consider what he had just eaten a meal, but merely something to whet his appetite. He ordered hot broth with crumbled bread and the meat of a sheep’s head, and ate to his heart’s content. He left the place only to pick and choose among such sweets as baseema, kunafa, and basbousa, as though afflicted by a mania for food. Just before midnight he returned to the hotel, so drunk with food he was nearly passing out. Locking his room, he experienced an unexpected feeling of sluggishness creeping through his limbs. Still with his trousers and shoes on, he threw himself down on the bed without turning off the light. What was it that lay crouched on his stomach, chest, and heart? What was it that stifled his breathing? Who was it that grasped his neck? He thought of calling for help, of searching for the bell, of using the telephone, but he was quite incapable of moving. His hands and feet had been shackled, his voice had gone. There was help, there was first aid, but how to reach them? What was this strange state he was in that wrested from a man all will and ability, leaving him an absolute nothingness? So, this is death, death that advances with no one to repulse it, no one to resist it. In his fevered thoughts he called upon the manager, upon Nuh, upon Othman, upon the fortune, the bride, the woman, the dream. Nothing was willing to make answer. Why, then, had this miracle taken place? It doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t make sense, O Lord.

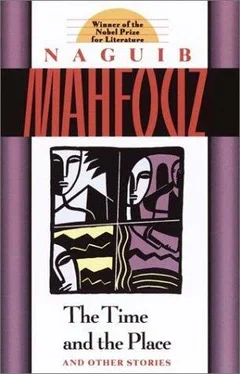

Naguib Mahfouz

The Time & The Place

Naguib Mahfouz was one of the most prominent writers of Arabic fiction in the twentieth century. Born in Cairo in 1911, he began writing when he was seventeen. Over his long career, he wrote nearly forty novel-length works and hundreds of short stories, ranging from re-imaginings of ancient myths to subtle commentaries on contemporary Egyptian politics and culture. His most famous work is The Cairo Trilogy (consisting of Palace Walk, Palace of Desire , and Sugar Street ), which focuses on a Cairo family through three generations, from 1917 until 1952. In 1988, Mahfouz became the first writer in Arabic to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He died in August 2006.

Born in Vancouver, Denys Johnson-Davies began studying Arabic at the School of Oriental Studies, London University, and later took a degree at Cambridge. He has been described by Edward Said as “the leading Arabic-English translator of our time,” and has published nearly twenty volumes of short stories, novels, and poetry translated from modern Arabic literature. He lives much of the time in Cairo.