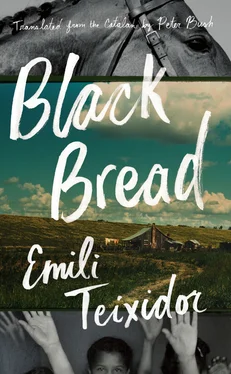

They called him Grandfather Hand or Old Hand because he’d worked there as a farmhand before marrying Grandmother Mercè. When Grandmother became a widow, the farmhand married her, even though he was much younger. As he came from a family of ten or twelve children and had spent all his life among mares, cows and sheep, by the age of eight or nine he’d started working with livestock and when he wasn’t being a shepherd boy he worked as a farmhand round-and-about or sheared sheep when the flocks were down for winter. After the first years of their marriage, as soon he could, he persuaded the masters to buy more sheep and a good ram and became their stockman, the main shepherd, spending half the year in the mountains with the other shepherds who organized it so they could take turns in the pasture land, doing shifts, as he called it. Dad Quirze, Grandmother Mercè’s son with her first husband, I mean Ció’s husband, and Bernat, the second-born, could manage the farm without him. Better that way, he’d say, because the young’uns — Grandfather Hand always called them the young’uns — had known him as a farmhand and couldn’t get used to thinking of him as their stepfather. That’s why they called him Old Hand, rather than Grandfather Hand, as we did.

At some point in the day the whole household paraded past Grandmother Mercè, who by early morning was already perched on her fireside throne, with her sewing and knitting basket on the floor, her long skirts down to her feet, her black headscarf — Father Tafalla called it her comforter — in place and glasses sitting on the end of her nose. She didn’t budge even for meals. We put her plates on a stool she pulled out from under the pew, while the others sat around the table and ate in a bad temper, staring into the fire. Ció, and often Enriqueta, if she arrived early from her work in Vic, set and waited on table. The men didn’t do a thing, didn’t even fetch a glass of water or go down to the wine cellar of Saint Ferriol, the patron saint of wine, to fill their wine-jars. Everything had to be ready when the men came in from the fields or stables. Some meals were eaten in complete silence, the logs crackling on the fire the only sound. It was as if the men were ground down by their worries. Or perhaps it was the winter, fog, ice, frost, snow or rain that was preoccupying them as if they were a plague that might infect the animals or crops. Perhaps it was being forced to live together day in, day out that made them hate each other. Ció often made us three eat before or after the men. She called us the kids or nippers, even though by then Quirze was a big lad, as well as a rogue, or so Grandmother reckoned, and also a rapscallion, a word she borrowed from Father Tafalla.

Mid-afternoon, if it didn’t come earlier, Aunt Enriqueta took Grandmother Mercè her newspaper from Barcelona. We all knew her reading time was sacred. We had to keep completely silent in the kitchen until she’d finished reading La Vanguardia . Even Ció and Aunt Enriqueta, if they were washing the dishes or preparing an afternoon snack, depending on when Enriqueta arrived, tried to leave the noisiest chores until after she’d read her daily paper.

When Grandmother put the newspaper down on her skirt, she’d sigh long and wearily, as if she’d just travelled around the world, and comment: “For Christ’s sake, the allies are never going to get here in time! If Churchill and Roosevelt really knew what’s happening here, it would be a different kettle of fish.”

At night, before going up to bed, when the men were milking and the women were putting hot embers in the “donkey” bed-warmers — they called them “monks” as well, though sometimes they used huge, hot stones in a pillowcase — we three and Aunt Enriqueta, and often Uncle Bernat and the occasional hand asked Grandmother Mercè to tell us a story about the woods, and better still if it could be a scary one.

“First we must say our rosary prayers,” she’d say, extracting a string of black beads from her pocket.

“No, later, later…” we protested.

“No, not later, because you’ll fall asleep with my first mystery,” she grumbled.

“You just see, we won’t fall asleep today.”

Grandmother Mercè gave a knowing smile, and started on the story we’d specially requested. We knew them all, she’d told them time and again. The best were the ones about the girl who was beheaded in the middle of the woods when she was coming back with her friends from the factory in Mother’s town, or the one about the heroes of the battle of Stalingrad, who didn’t leave a single German standing, or the one about the old woman from the farmhouse in Cós who was left all alone one night and the devil appeared and carried her off live to hell, or Josephine Baker and the dress made from bananas that covered her privates who was so beautiful — even though she was as black as Arumí chocolate — and all the men wanted to marry her, or about the day Death didn’t come in time to take away the sick man who had mocked it and never made the rendezvous they’d agreed, or the French maréchal under sentence of death who on the night before his execution asked to play a game of chess with the Grim Reaper to see who would win, or the one about the world stuffed into a bucket of dirty clothing because it was so disgusted by mankind… Every single one authentic, Grandmother Mercè assured us. Authentic , she said. There were words like that, which she alone used, and we suspected that many of the words she now liked to use, like allies, armistice, treaty, resistance, allegations, fascism, legality, exile… she’d collected from the pages of her daily newspaper.

“Once upon a time there was, and you must believe that this is truly authentic…”

We lived up the plum tree until autumn came.

When the days began to shorten, nighttime sometimes caught us in the tree and Ció had to shout to us to climb down.

“Blessed kids!” she’d gripe after she’d stopped bawling, when we were standing in front of her. “You spend too much time playing for the age you are. One of these days a branch will break and you’ll crack your skulls open.”

“They’re all up to no good, they run riot,” said Grandmother, keeping her eyes glued to the knitting needles her fingers moved over her ample bosom, while she kept her arms still.

The Novíssima didn’t start until early October, and for the early weeks of school when we three chased back to the farmhouse, the first thing we did was put our cardboard satchels on the stone bench in the entrance, go into the kitchen and grab the slices of bread spread with oil and sugar or wine and sugar Ció or Grandmother had prepared for us on a dish in the middle of the table, then we’d run with our snacks to the plum tree so we could climb up and eat them lounging back on our branches.

Now and then, when a colder breeze blew and the reddish sun didn’t linger as it did in summer, when evenings were like the inside walls of a bread oven that retained the heat from the flames of logs burnt moments before, we took blankets up the tree to wrap around us and fought off as best we could the cold and early nighttime damp coming out of the woods. The damp, stifling heat, treacherous cold or gusting wind all emerged from the forest that was like an immense belly or huge pantry full of small compartments that hoarded all the good and bad luck that existed in the world. Up in our plum tree we often thought we’d be able to catch the moment when the leaves changed colour, but the change in the leaves, like moulting feathers, always happened from one day to the next; overnight an area of wood turned a dazzling saffron yellow, and a few days later the beech trees had turned wine-red, soon to be followed by the silvery white of the poplars, the dark brown of the chestnut trees, the humid greens… We looked at each other in dismay, as if someone was making fun of our wait and one year Cry-Baby suggested we stay there the whole night to catch the precise moment of change.

Читать дальше