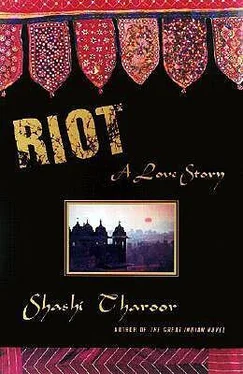

How can such a religion lend itself to “fundamentalism”? That devotees of this essentially tolerant faith want to desecrate a shrine, that they’re going around assaulting Muslims in its name, is to me a source of shame and sorrow. India has survived the Aryans, the Mughals, the British; it has taken from each — language, art, food, learning — and grown with all of them. To be Indian is to be part of an elusive dream we all share, a dream that fills our minds with sounds, words, flavors from many sources that we cannot easily identify. Muslim invaders may indeed have destroyed Hindu temples, putting mosques in their place, but this did not — could not — destroy the Indian dream. Nor did Hinduism suffer a fatal blow. Large, eclectic, agglomerative, the Hinduism that I know understands that faith is a matter of hearts and minds, not of bricks and stone. “Build Ram in your heart,” the Hindu is enjoined; and if Ram is in your heart, it will matter little where else he is, or is not.

Why should today’s Muslims have to pay a price for what Muslims may have done four hundred and fifty years ago? It’s just politics, Priscilla. The twentieth-century politics of deprivation has eroded the culture’s confidence. Hindu chauvinism has emerged from the competition for resources in a contentious democracy. Politicians of all faiths across India seek to mobilize voters by appealing to narrow identities. By seeking votes in the name of religion, caste, and region, they have urged voters to define themselves on these lines. Indians have been made more conscious than ever before of what divides us.

And so these fanatics in Zalilgarh want to tear down the Babri Masjid and construct a Ram Janmabhoomi temple in its place. I am not amongst the Indian secularists who oppose agitation because they reject the historical basis of the claim that the mosque stood on the site of Rama’s birth. They may be right, they may be wrong, but to me what matters is what most people believe, for their beliefs offer a sounder basis for public policy than the historians’ footnotes. And it would work better. Instead of saying to impassioned Hindus, “You are wrong, there is no proof this was Ram’s birthplace, there is no proof that the temple Babar demolished to build this mosque was a temple to Ram, go away and leave the mosque in place,” how much more effective might it have been to say, “You may be right, let us assume for a moment that there was a Ram Janmabhoomi temple here that was destroyed to make room for this mosque four hundred and sixty years ago, does that mean we should behave in that way today? If the Muslims of the 1520s acted out of ignorance and fanaticism, should Hindus act the same way in the 1980s? By doing what you propose to do, you will hurt the feelings of the Muslims of today, who did not perpetrate the injustices of the past and who are in no position to inflict injustice upon you today; you will provoke violence and rage against your own kind; you will tarnish the name of the Hindu people across the world; and you will irreparably damage your own cause. Is this worth it?”

That’s what I’ve been trying to say to people like Ram Charan Gupta and Bhushan Sharma and their bigoted ilk. But they don’t listen. They look at me as if I’m sort of a deracinated alien being who can’t understand how normal people think. Look, I understand Hindus who see a double standard at work here. Muslims say they are proud to be Muslim, Sikhs say they are proud to be Sikh, Christians say they are proud to be Christian, and Hindus say they are proud to be … secular. It is easy to see why this sequence should provoke the scorn of those Hindus who declaim, “Garv se kahon hum Hindu hain” — “Say with pride that we are Hindus.” Gupta and Sharma never fail to spit that slogan at me. And I am proud of my Hinduism. But in what precisely am I, as a Hindu, to take pride? Hinduism is no monolith; its strength is found within each Hindu, not in the collectivity. As a Hindu, I take no pride in wanting to destroy other people’s symbols, in hitting others on the head because of the cut of their beard or the cuts of their foreskins. I am proud of my Hinduism: I take pride in its diversity, in its openness, in religious freedom. When that great Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda electrified the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, he said he was proud of Hinduism’s acceptance of all religions as true; of the refuge given to Jews and Zoroastrians when they were persecuted elsewhere. And he quoted an ancient Hindu hymn: “As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O lord, the different oaths which men take … all lead to thee.” My own father taught me the Vedic sloka “Aa no bhadrah kratvo yantu vishwatah” — “Let noble thoughts come to us from all directions of the universe.” Every schoolchild knows the motto “Ekam sad viprah bahuda vadanti” — “Truth is one, the sages give it various names.” Isn’t this all-embracing doctrine worth being proud of?

But that’s not what Mr. Gupta is proud of when he says he’s proud to be a Hindu. He’s speaking of Hinduism as a label of identity, not a set of humane beliefs; he’s proud of being Hindu as if it were a team he belongs to, like a British football yob, not what the team stands for. I’ll never let the likes of him define for me what being a Hindu means.

Defining a “Hindu” cause may partly be a political reaction to the definition of non-Hindu causes, but it is a foolish one for all that. Mahatma Gandhi was as devout a Rambhakt as you can get — he died from a Hindu assassin’s bullet with the words “Hé Ram” on his lips — but he always said that for him, Ram and Rahim were the same deity, and that if Hinduism ever taught hatred of Islam or of non-Hindus, “it is doomed to destruction.” The rage of the Hindu mobs being stoked by the bigots is the rage of those who feel them-selves supplanted in this competition of identities, who think that they are taking their country back from usurpers of long ago. They want revenge against history, but they do not realize that history is its own revenge.

from transcript of Randy Diggs interview

with Superintendent of Police Gurinder Singh

October 14, 1989

RD: I’ll accept that drink now, thanks. What happened next?

GS: Lucky and I quickly realized that the only way the mob could be prevented from assembling below the house — the house from which the fucking bomb was thrown — was by getting there first ourselves. I grinned, and said to Lucky: “DM-sahib, time for us to take charge.”

RD: They could have thrown their bombs at you.

GS: That was the risk, clearly. But it was an acceptable risk. To prevent a far bigger tragedy.

RD: And did the mob give way?

GS: We had to keep shouting to the pissing processionists that they should stay back. That we were taking charge of the situation. Fortunately their more rabid leaders, people like Bhushan Sharma or Ram Charan Gupta, were not in that part of the crowd. They were in the front of the motherloving procession, leading it for glory, and word had not reached them yet from where we were. Most of the crowd listened to us and stayed at bay. Inevitably, though, some bloody idiots with the brains of a squashed cockroach edged forward behind us as we headed towards the house.

RD: I’ve met Ram Charan Gupta.

GS: Our next member of Parliament for Zalilgarh. Or so the pissing political pundits tell me. Ironically, considering what we think of each other, he publicly praised my handling of this particular incident.

RD: What did you do?

Читать дальше