“Bye now. And you ,” John Doe meant me. “ You take care.”

It was coming down hard, and after Mo started up the car, he had to get back out to brush off the snow that was flaking up the windshield.

Through my window, I saw the outside garbled with white freeze, so that the roadside shimmered brightly even in the dark of the night. I stuffed my fingers in the open bottle in my pocket to make certain the pills, my new little tickets back to the life I’d chosen, wouldn’t shake. I would not be caught. I would not be hemmed in. I was holding my fate in my hands again.

But when I got home and opened the bottle, suddenly I didn’t want to take the pills. Before the accident, the hardest drug I’d ever taken was uncoated aspirin, and I hated the fuzz of painkillers. In theory it had seemed a good idea, but there was a difference between thinking and doing. A first degree murder is willful and premeditated. Second degree is not. And then there was voluntary manslaughter: a crime of passion.

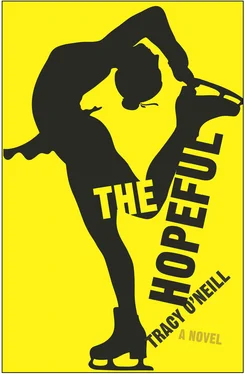

I looked at the clock— tick tock tick tock tick— and wasn’t this what I should have been grateful for? That I had so much of my life ahead and not all of it behind? There were many more things I hadn’t done, far more than I had. I brushed my teeth, I read a poem called “Stillborns” at school, I wanted strange iced movements and glimpsed things stranger in the moments I believed. I blew windmills and shivered through August in indoor rinks, spreading obtuse against nature, one toe towards the sky. Counting the miracles I did, I could spend some breathless minutes. Counting the others would never end. I could count on mediocrity or I could take the amphetamines to gamble on Olympic gold. I’d never get myself to the shape and size of an athlete without the pills. I needed to overcome nature.

Before I’d ever tried it, all I knew about figure skating was that you could fall doing it, and I didn’t want to fall. I rubbed my forehead into a false fever to avoid going to Lizzie Swenson’s ice skating birthday and congested my voice by way of excuse. “Bum, by nose is stuffy,” I said. “Bum, by tubby aches.”

“You’re going,” my mother said, and she belted me into the passenger seat to drive to the skating rink.

At the arena, the other girls waddled to the ice, their bodies listing like metronomes, and I pointed to my skate boots, said they were too loose, then too tight. I hoped I could make the skate lace adjustments last the duration of the party. The place smelled like microwaved hot dogs and faux cheese nachos, and I was sickening watching colored parkas struggling in orbs around the rink.

“Too tight,” I said once more.

“Just right,” my mother said and she urged me onto the ice.

The other girls were arm-in-arm stuttering around the rink, holding each other up and screaming. I was smothering the rink barrier with my entire body, bargaining with gravity. My ankles caved in the wrong directions and I felt a breath away from falling, even still holding onto the wall.

“Look at the other little girls having fun. Don’t you want to have fun like the other girls?”

“No,” I said. I watched my breath frost out into a fearful little puff.

“What’s wrong with Ali?” Lizzie Swenson’s mother had suddenly appeared by my mother’s side. “Is Ali afraid?”

“No,” my mother and I said.

“She looks afraid. She can come sit and have a cocoa instead if she’d like.”

“I’m not afraid,” I said. Pity made me angry, so I let go of the plastic barrier, and for the first time in my walking life, I knew I couldn’t count on standing. I knew I had to hold myself up, push away from my mother or else fall. One step, two steps, three steps, and I could fall at any second. On ice every stroke forward is a discrete victory, and suddenly I saw that these victories had added up to passing the mass of little girls. I forgot about the party. I was in a waking dream of flight, and all I could think, blue-lipped and creating the elation of wind, was again! Again! Again!

After that, I wouldn’t wear shoes inside for weeks. I ran stockinged to the kitchen and threw myself, gliding on the linoleum floor. “You’ll kill yourself,” my mother warned as she washed dishes, but I couldn’t be stopped. When finally I slid into a corner of the stove and had to be sutured through the temple, she bought me a pair of skates, and the rest was the history of the best time of my life.

I would take the pills.

IT’S been a bad day, and I just want to sleep. Doing nothing is more exhausting than doing, I’ve realized. Because doing nothing always means thinking.

The doctor is harried today. Maybe she’s had a bad day too.

Let me get this right—

I’d never stand in your way, doc.

And I appreciate that. Now, tell me if I am correct in my summary of our previous session. Your mother decided to send you to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings to deter you from drinking after a drunk driving accident in town. You attended the meeting with your cousin Mo. There, a man who identified himself as John Doe sold you amphetamines. You believed amphetamines to be a vehicle to returning to your life as a skater.

Well truncated, I say. But something about the way she describes my plan makes it sound ridiculous now. The truth is, even before I couldn’t skate anymore, there were probably two hundred girls in the country as good or better than me. I wasn’t a shoo-in. I was only a hopeful. But for the chance even to be hopeful, wasn’t it all worth it?

And you believed this man when he referred to himself as John Doe?

Are you calling me gullible?

I’m calling you nothing at all. I’m asking if you believed this man when he told you to call him John Doe. She pulls her hair behind her ear, as though to clearly show the honesty of her face. It’s a square face, disciplined in its plainness. Plainness isn’t honesty, though, and I did hear her incredulity at my naiveté, my belief in the plan.

There are more improbable paradoxes than an anonymous name, I say.

And though many of your loved ones, including your father, your mother, Mark and your cousin Lucy, urged you to consider new activities, you suspected that the use of psychostimulants was a savvier path to happiness.

I had limited empirical proof, I admit. However, I was willing to try anything.

Except, say, cheerleading, she smiles.

Except cheerleading.

And why is that? Why were you more willing to try this, yet unwilling to try an afterschool activity with very few risks at all?

Have you seen what cheerleaders do, the day of a football game, Doctor? They wear football player jerseys to school. They’re swooning support staff. Not only are they cheering for the accomplishments of the boys, they walk around wearing some guy’s spare uniform the day of the game. And do the football players ever support the cheerleaders? No. They look up their skirts.

So you found the lack of reciprocity unappealing.

I wasn’t trying to get anything from anyone. Therapy, I’ve noticed, is an act of translation. I speak, she translates. No one understands.

Yet you did ask for John Doe to give you pills, urged him, even.

I did, I say. But I think about that night and wonder if it was I who urged him or if he urged me. He found me, not I him.

Are you able, then, to recognize that you had formed a relationship in which your desires depended on another individual?

Please don’t gloat, Doctor.

I’m not gloating. I’m asking if you can recognize a fact. She looks as though it’s I who have insulted her. It’s so easy for her to ask the questions, sit in her chair, take notes. But this is my life.

Fact recognized. Are we done?

Читать дальше