The letter from Shanghai was thirty pages long and written in a spidery hand; after some minutes I tired of watching my mother struggle through it. I went to the front room and gazed at the neighbours. Across the courtyard, I saw a miserable Christmas tree. It looked like someone had tried to strangle it with tinsel.

Rain gusted and the wind whistled. I brought my mother a glass of eggnog.

“Is it a good letter?”

Ma set the pages down. Her eyelids looked swollen. “It’s not what I expected.”

I ran my finger across the envelope and began to decipher the name on the return address. It surprised me. “A woman?” I asked, suddenly afraid.

My mother nodded.

“She has a request,” Ma said, taking the envelope from me and shoving it beneath some papers. I moved closer as if she was a vase about to slide off the table, but Ma’s puffy eyes conveyed an unexpected emotion. Comfort? Or maybe, and to my astonishment, joy. Ma continued: “She’s asking for a favour.”

“Will you read the letter to me?”

Ma pinched the bridge of her own nose. “The whole thing is really long. She says she hasn’t seen your father in many years. But, once, they were like family.” She hesitated on the word family. “She says her husband was your father’s composition teacher at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. But they lost touch with one another. During the difficult years.”

“What difficult years?” I began to suspect that any favour would involve American dollars or a new refrigerator, and feared that Ma would be taken advantage of.

“Before you were born. The 1960s. Back when your father was a music student.” Ma looked down with an unreadable expression. “She says that your father made contact with them last year. Ba wrote to her from Hong Kong a few days before he died.”

A string of questions rose in me. I knew I shouldn’t pester her but at last, because I wished only to understand, I said, “Who is she? What’s her name?”

“Her surname is Deng.”

“But her given name.”

Ma opened her mouth but no words came out. Finally, she looked me straight in the eye and said, “Her given name is Li-ling.”

She had the same name as me, only it had been written in simplified Chinese. I reached for the letter. Ma put her hand firmly over mine. Forestalling my next question, she lunged ahead. “These thirty pages are about the present not the past. Deng Li-ling’s daughter arrived in Toronto but her passport can’t be used. Her daughter has nowhere to go, she needs our help. Her daughter…” Nimbly, Ma slid the letter into its envelope. “Her daughter will come and live with us for a little while. Do you understand? This letter is about the present.”

I felt sideways and upside down. Why would a stranger live with us?

“Her daughter’s name is Ai-ming,” Ma said, trying to lead me back. “I’m going to telephone now and arrange for her to come.”

“Are we the same age?”

Ma looked confused. “No, she must be at least nineteen years old, she’s a student. Deng Li-ling says that her daughter…she says that Ai-ming got into trouble in Beijing during the Tiananmen demonstrations. She ran away.”

“What kind of trouble?”

“Enough,” my mother said. “That’s all you need to know.”

“No! I need to know more.”

Exasperated, Ma slammed the dictionary shut. “Who brought you up? You’re too young to be this nosy!”

“But—”

“Enough.”

—

Ma waited until I was in bed before she made the telephone call. She spoke in her mother tongue, Cantonese, with brief interjections of Mandarin, and I could hear, even through the closed door, how she hesitated over the tones which had never come naturally to her.

“Is it very cold where you are?” I heard Ma say.

And then: “The Greyhound ticket will be waiting for you at…”

I took off my glasses and stared out the blurred window. Rain appeared like snow. Ma’s voice sounded foreign to me.

After a long period of silence I re-hooked my glasses over my ears, climbed out of bed and went out. Ma had a pen in her hand and a stack of bills before her, as if waiting for dictation. She saw me and said, “Where are your slippers?”

I said didn’t know.

Ma exploded. “Go to bed, Girl! Why can’t you understand? I just want some peace! You never leave me alone, you watch me and watch me as if you think I’ll…” She slapped the pen down. Some piece of it snapped off and ran along the floor. “You think I’m going to leave? You think I’m as selfish as he is? That I would ever abandon you and hurt you like he did?” There was a long, violent outburst in Cantonese, then: “Just go to bed!”

She looked so aged and fragile sitting there, with her old, heavy dictionary.

I fled to the bathroom, slammed the door, opened it, slammed it harder, and burst into tears. I ran water in the tub, realizing that what I really wanted was, in fact, to go to bed. My sobs turned to hiccups, and when the hiccups finally stopped, all I heard was water gushing down. Perched on the edge of the tub, I watched my feet distort beneath the surface. My pale legs folded away as I submerged.

Ba, in my memory, came back to me. He pushed a cassette into the tape player, told me to roll down the windows, and we sailed down Main Street and along Great Northern Way, blaring Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto, performed by Glenn Gould with Leopold Stokowski conducting. Tumbling notes cascaded down and infinitely up, and my father conducted with his right hand while steering with his left. I heard his humming, melodic and percussive, DA! DA-de-de-de DA!

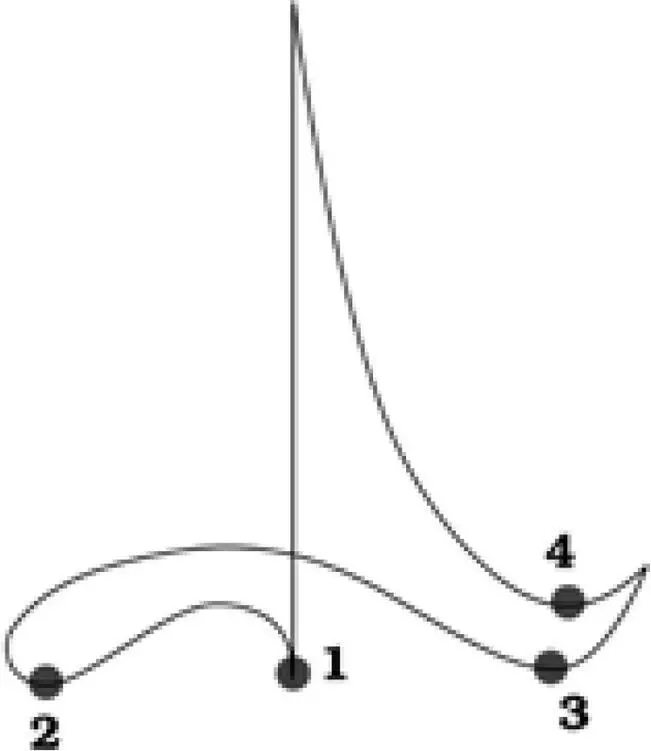

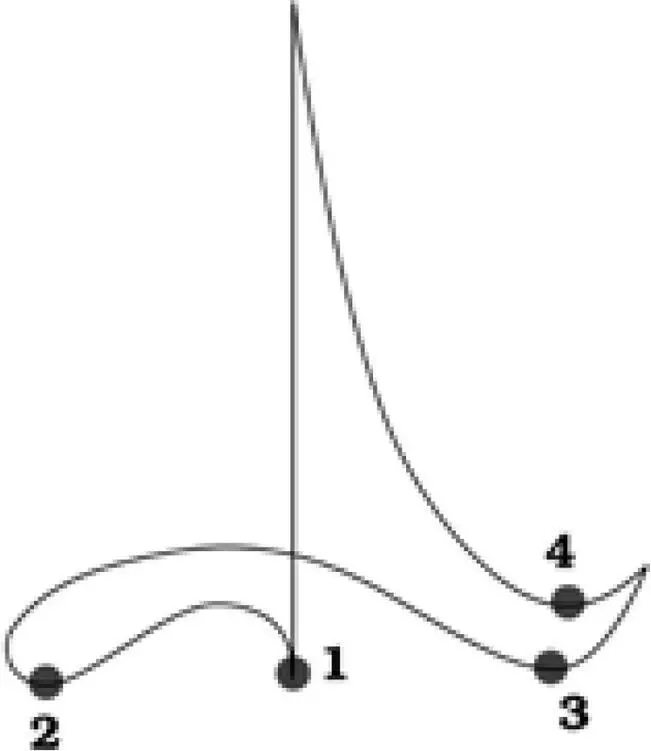

Da, da, da! I had the sensation that, as we paraded triumphantly across Vancouver, the first movement was being created not by Beethoven, but by my father. His hand moved in the shape of 4/4 time, the cliff-hanging thrill between the fourth beat and the first,

and I wondered what it could mean that a man who had once been famous, who had performed in Beijing before Mao Zedong himself, did not even keep a piano in his own home? That he made his living by working in a shop? In fact, though I begged for violin lessons, my father always said no. And yet here we were, crossing the city embraced by this victorious music, so that the past, Beethoven’s and my father’s, was never dead but only reverberated beneath the windshield, then rose and covered us like the sun.

and I wondered what it could mean that a man who had once been famous, who had performed in Beijing before Mao Zedong himself, did not even keep a piano in his own home? That he made his living by working in a shop? In fact, though I begged for violin lessons, my father always said no. And yet here we were, crossing the city embraced by this victorious music, so that the past, Beethoven’s and my father’s, was never dead but only reverberated beneath the windshield, then rose and covered us like the sun.

The Buick was gone; Ma had sold it. She had always been the tougher one, like the cactus in the living room, the only house-plant to survive Ba’s departure. To live, my father had needed more. The bath water lapped over me. Embarrassed by the waste, I wrenched the tap closed. My father had once said that music was full of silences. He had left nothing for me, no letter, no message. Not a word.

Ma knocked at the door.

“Marie,” she said. She turned the handle but it was locked. “Li-ling, are you okay?”

A long moment passed.

The truth was that I had loved my father more. The realization came to me in the same breath I knew, unquestionably, that my father must have been in great pain, and that my mother would never, ever abandon me. She, too, had loved him. Weeping, I rested my hands on the surface of the water. “I just needed to take a bath.”

“Oh,” she said. Her voice seemed to echo inside the tub itself. “Don’t get cold in there.”

She tried the door again but it was still locked.

Читать дальше

and I wondered what it could mean that a man who had once been famous, who had performed in Beijing before Mao Zedong himself, did not even keep a piano in his own home? That he made his living by working in a shop? In fact, though I begged for violin lessons, my father always said no. And yet here we were, crossing the city embraced by this victorious music, so that the past, Beethoven’s and my father’s, was never dead but only reverberated beneath the windshield, then rose and covered us like the sun.

and I wondered what it could mean that a man who had once been famous, who had performed in Beijing before Mao Zedong himself, did not even keep a piano in his own home? That he made his living by working in a shop? In fact, though I begged for violin lessons, my father always said no. And yet here we were, crossing the city embraced by this victorious music, so that the past, Beethoven’s and my father’s, was never dead but only reverberated beneath the windshield, then rose and covered us like the sun.