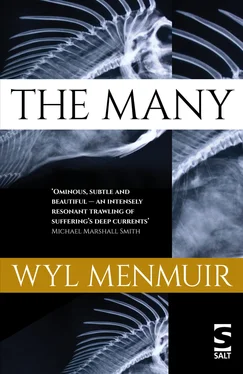

Wyl Menmuir - The Many

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wyl Menmuir - The Many» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Salt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Many

- Автор:

- Издательство:Salt

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Many: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Many»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Many — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Many», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When he stands and emerges into the light, he looks around and as his eyes adjust again, he sees two sheep, huddled together, just a few yards away in the field, eating grass with some urgency and ignoring him and he is glad he has not been seen by anyone else, panicking over a couple of sheep trapped in a cave in a country field. Unnerved, he jogs back to the field boundary, climbs the wall again and turns to run back towards the village.

He slows to a walk a hundred feet or so from the house, and looks at it alongside the others on the row. As he does, he has the feeling if it were not for its position on the road, flanked as it is by two other houses in the same style, he could walk past Perran’s and not know it at all.

Back inside and sitting at the kitchen table, Timothy scribbles an advert for a decorator onto a piece of card he has ripped from one of the packing boxes, which he later takes down to the café by the beach. It seems to be the only place open aside from the pub and the store, and the girl behind the counter says he can put it on the wall by the door for a week.

After only a few hours a note is pushed through the door of his house. He reads it, puts it on the kitchen table and watches it for a while, before consigning it to the kitchen bin. It was another bad idea.

The next time he walks down to the seafront, and passes the café, the same waitress who told him he could put up his advert catches him as he walks by the open door.

‘You want someone to help with that house?’

He nods, though he is not now sure that he does.

‘Tracey. My sister. She’ll do it fine. She’s done work in most people’s houses round here. She’ll do fine. I’ll send her over ’round three.’

And it is arranged. The waitress has retreated back into the café. Though he does not want anyone to come to the house now, he cannot find a good enough reason to put her off, so he continues his walk between the café and the winch house propped up against the wall that separates the road from the beach.

Clem is sitting outside on the deep concrete step looking out at the sea and Timothy sits down next to him. Clem says nothing, and Timothy wonders whether he has heard him arrive.

‘I ran out beyond the village this morning,’ Timothy says. ‘I had a look at those stone structures, the ones in the field. Do you know what they are, what they were? They look old. Are they storehouses? Or graves? Are they symbolic of something?’

‘The barrows?’ Clem replies and his voice is far away. ‘No, no one knows what they’re there for. No meaning in them I know of.’

Clem settles back into his silence and after a minute or so Timothy wonders whether the other man has forgotten he is there.

‘Tell me about Perran then,’ Timothy says. ‘Or at least tell me why you won’t talk about him.’

The winchman says nothing, but continues to stare out to where the gulls sit on the rocks at the mouth of the cove, waiting on the return of the fleet. Timothy has a feeling it is not Clem sitting next to him at all, but that he is out with the birds on the rocks, watching with them in hope of a catch for the fleet, and in hope of their safe return. That the man beside him is a golem, an empty shell left to sit by the water while its inhabitant walks elsewhere. Timothy stands and walks down off the concrete step onto the stones, and Clem speaks before he has gone five yards.

‘What is there to tell?’

Clem’s voice still sounds as though he is talking at a distance.

‘What is there I could tell you would make him real to you?’

He is silent then a while longer and Timothy thinks he is finished and the stones crunch beneath his feet as he turns to walk on.

‘You want to hear me tell you he was a good man, and one who worked hard for his lot. A grafter. You’ll want to hear he was the best of us, the one who looked out for all the rest and never tired, and never bitched and never moaned when the fish dried up, and kept the fleet going until they made their way back.’

Timothy feels each of the words as though they are stones from the beach pitched into dead calm water. Each one drops into the deep and makes its way down through forests of kelp to settle heavy on the sea floor. Timothy feels his legs start to buckle beneath him and he wants to sit down again before he falls down onto the stones.

‘You want me to tell you he was gifted. Or a gift. A talisman. That when I took over from him, I was stepping into shoes I could not hope to fill. There’s some will tell you that, sure.’

More stones falling one after the other into the water, each one small and heavy, and each one heavier than the last. The words reach him as if transmitted over a vast distance and he feels each fall on him like a mote of infinite density that punctures and passes through him.

‘What do you want him to be? What do you want to feel about him? You want to feel proud? You want to feel he was okay, that he lived out a life he was happy with?’

The distance with which Clem had spoken earlier is receding now, and with each sentence, he gets louder and closer to Timothy, though as far as he can tell, the older man has not moved from where he is sitting, on the concrete step. Clem’s voice has risen too, as though the question has dragged him back from his place out with the birds on the rocks, and his words are sharp round the edges, as with smooth stones that break and splinter when they are thrown down among others on the beach. Timothy wants to be far away from Clem now. He wants to be far away from this village, out in the open space of the sea, though as he looks out that way, the line of container ships on the horizon stares backs at him. He stands and walks away from Clem, who is still sitting outside the hut, staring out onto the water, and the winchman’s words follow him until he is out of sight of the beach and back up on the road.

Timothy wanders back up through the village and as he walks along the top row, he sees there is a girl or woman waiting for him on the front step of the house.

Tracey’s bleached hair makes her look younger than she is, and when she moves it aside from where it has fallen across her face, he sees her skin, sun-scarred and pocked. Standing on the doorstep talking to him, she is already looking around him into the hallway with open curiosity, though why this is he cannot understand, as she has arrived to work in the house and she will be inside soon enough. He wonders again whether this move has been a mistake, though she is here now and soon enough in the house, wandering from room to room, looking appraisingly, a little shocked, unimpressed, he cannot tell. He leaves her to her exploration and sits in the kitchen, not wanting to put the kettle on in case she takes it as an invitation to stay any longer.

‘I know what this house needs,’ she says. ‘Leave it to me, I’ll make a start now.’

There is something suggestive in the tone of her voice. Timothy considers telling her he has not made up his mind yet about taking her on for the job, but she has taken out a notepad already and is scribbling in it with a pencil stump. He feels obliged to take her instruction, and he picks up his jacket from the back of a kitchen chair and leaves through the side door.

By the time Timothy returns to the house, Tracey has gone, though as he walks through the house to check, he has the passing thought she might be waiting for him in the bedroom. She is not, but she has left behind her the smell of smoke, which lingers throughout the rooms and on the stairs, and he finds a small pile of cigarette ends by the doorstep. He walks through the house and sees she has been trialling swatches of paint over the walls in the front room, lines of powder blue by the chimneybreast. It’s not what he would have chosen, and he starts to wonder, now he has invited someone else into the house to make decisions, what his role here might be. He paces the house and thinks on the different ways in which he might rid himself of her.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Many»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Many» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Many» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.