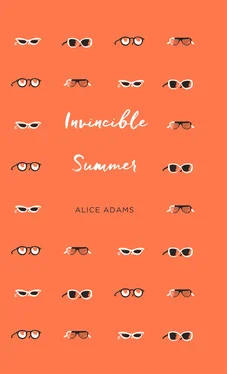

Alice Adams

Invincible Summer

For my family, blood and otherwise

Au milieu de l’hiver, j’apprenais enfin qu’il y avait en moi un été invincible.

In the depths of winter, I finally learned that there lay within me an invincible summer.

Albert Camus, ‘Retour à Tipasa’, 1952

‘Okay, here’s one. If you could know the answer to any one single question, what would it be?’

Eva was lying on her back and looking up at the sky as she spoke. Summer had finally arrived, late that year, and the feeling of sun on skin combined with the wine and Lucien’s shoulder beneath her head was intoxicating. She had sat the last of her first-year exams that morning and would be going home for the summer the next day, but in a couple of months she’d be right back here in a life that was as far removed from her old world as she’d dared to hope it would be when she’d set off for university the previous autumn.

The four friends were clustered on a blanket close to the top of Brandon Hill. They hadn’t bothered to enter the stone tower perched at the hill’s brow and climb the spiral staircase to the viewing platform, but in any case their vantage point afforded them an impressive view of the city, out across the treacly river and past the derelict warehouses towards the endless sprawl of streets and houses beyond. In the long grass by their feet were two open wine bottles, the first propped upright in one of a pair of battered lace-up boots, the other lying on the ground spilling its last drops onto the earth.

Sylvie rolled over onto her stomach and brushed a few strands of coppery hair from her eyes. ‘Any question at all?’

‘Yes,’ said Eva. ‘Foof.’

‘Huh?’

‘That was the sound of the genie disappearing after you wasted your question.’

Sylvie glared at her. ‘That’s not fair. I’m having another one. I want to know the meaning of life.’

‘That’s not actually a question.’ Benedict elbowed her gently in the ribs. ‘Anyway, the answer would probably turn out to be forty-two, and then you’d have wasted your question again.’

Sylvie tugged her index finger and thumb sharply along a stalk of sedge grass, strimming the seeds into her hand and then blowing them into his face. ‘Okay, smarty-pants. What would you ask?’

Benedict blinked. ‘I’d have to think about how to phrase it, but basically I would want to know the grand unifying theory for the universe.’ He thought for a moment. ‘Or else, what happens when we die.’

‘How about next week’s lottery numbers?’ asked Eva lazily.

‘You’d have to be insane to waste your question on something so banal,’ said Benedict, prompting a scowl from Eva. It was all very well to think there was something trivial about money when you came from a family like Benedict’s, but when you’d grown up in a small Sussex town short on glamour and long on stolid conformism the world was a different place. Benedict would never understand what it felt like to get up every weekend and trudge to work in a mindless supermarket job as Eva had for the four long years before she arrived in Bristol, where the same kids who regularly threw her bag over a hedge on the way to school would come in and pull things off the shelves just to get her into trouble. She couldn’t win: if she ignored them she ran the risk of getting fired, but if she called security they’d make sure her bag landed in a puddle on Monday.

In a place like that almost anything could make you an outcast: wearing the wrong clothes, doing too well in exams, not being able to talk about the ‘in’ TV shows because your father didn’t believe in having a TV. The only real glimpse of daylight had come in the form of Marcus, who was briefly her boyfriend, because no matter how unpopular you were there was always a teenage boy whose libido could propel him past that barrier. Marcus was himself quite popular and had taken a surprising interest in Eva, and for a few short months she had been his girlfriend and basked in a grudging acceptance.

The relationship led to the pleasing if rather undignified loss of her virginity in the woods behind the school after half a bottle of cider on a bench, which apparently constituted both date and foreplay. Marcus had eventually grown resentful and dumped her after a much-anticipated afternoon in bed while his parents were away ended prematurely before he’d even removed his trousers, and Eva had ill-advisedly tried to lighten the mood by cracking a few jokes. She’d read in Cosmopolitan that it was important for couples to be able to laugh together in bed, but then, the article had also said that slapping the male genitalia as if lightly volleying a tennis ball was a good idea and that hadn’t gone down particularly well either. At least by that time she’d made it into the relative safety of the sixth form, but while her life had become bearable it was hardly the stuff that dreams were made of. The day before she finally left for university Eva had taken the polyester uniform she’d worn for four long years of Saturdays out onto the patio and set fire to it, making a vow into the smoke that she was never going back.

‘What about you, Lucien?’ Benedict nudged Sylvie’s brother’s leg with his own, his voice breaking through Eva’s reverie. ‘What’s your question?’

‘Christ, I don’t know. A list of everyone who’s ever got their jollies thinking about me?’

Eva closed her eyes to avoid involuntarily glancing at him and hoped her cheeks weren’t visibly reddening. Nobody knows, she told herself. They can’t read your mind to see the Atlas of Lucien mapped out there, from the messy dark hair to the freckle on the inside of his surprisingly delicate wrist.

Sylvie let out a long, low moan of disgust and Benedict laughed. ‘I don’t think I’d like that,’ he mused. ‘It would take all the mystique out of things.’

‘The virginity is strong with this one,’ taunted Lucien in his best Yoda voice.

‘Hardly,’ muttered Benedict. ‘Anyway, there’d probably be some hideous people on there. Your sports master from school or someone like that.’

‘Okay, women only. Under the age of thirty.’ Lucien leant over to retrieve the almost empty wine bottle from Eva’s boot, carelessly dislodging her head from his shoulder as he did so.

Eva sat up, trying to look as if the brush-off didn’t bother her. Typical of Lucien, she thought, to pull her down onto his shoulder like that and then push her away. They’d been doing this dance for most of the year since she’d arrived in Bristol and her new friend Sylvie had introduced her to her hard-living elder brother. Lucien wasn’t a student; he described himself as an entrepreneur, though Eva was hazy on the detail of what that actually involved. Sylvie had chosen to study at Bristol only because Lucien was already living there, presumably doing whatever it was that he did in the little time that he didn’t spend loitering around halls with the rest of them.

‘Right,’ said Sylvie, levering herself up from the ground and brushing the grass off her jeans. ‘I can’t listen to any more of this. I’m off to the library to pull an all-nighter, my last essay’s due in tomorrow.’

Sylvie was known for her aversion to writing the essays that she always seemed slightly appalled were required by her History of Art course, and claimed to find it impossible to work without a deadline less than forty-eight hours away. The degree was merely intended to buy her some time on her trajectory to being a revered artist, which, it was generally accepted by the group, was inevitable. The ingredients were all there: a prodigious and obsessive talent for drawing and painting, a quirky, original eye, supplemented by striking good looks and a tough, irreverent attitude to life. She had a certain shine, a vividness about her; she was just one of those people who generated their own gravity, causing people to cluster around her and try to please her. It was impossible to imagine her being anything other than a great success.

Читать дальше