Except for the children. The boys came very first — and there was still the call back to Barrow.

And then, after lunch, and before the hairdresser’s — because she had to have her hair done for this evening — there were also the place cards still to inscribe, the guest list to read over, the seating chart to arrange.

All the small details.

She would book Jamie on the Friday 3:35 p.m. flight out of Heathrow. She could do that right now while she remembered, then send a text to the embassy asking whether someone was coming in on the same flight to share a car into the city. At least that would be taken care of. Saturday morning, Jamie would sit down with her and Edward, and they would talk the whole situation at Barrow through, the three of them, face-to-face. They’d sort Jamie out before putting him back on a flight to London whenever his suspension period was over. He’d be chastened; he’d do better in the future. They would talk to the school about getting him the support he needed.

She reached into her purse for her cell phone, then pulled her hand away. She’d finish here first: what she wanted were some flowers that grew in Ireland.

“Bluebells,” she said to Jean-Benoît patiently. “Primroses.”

“Zis flower, I do not know.” Jean-Benoît crossed his arms across his apron. His chin made a sharp little square; his eyes looked almost black behind his glasses. “Madame, why don’t you just tell me what you want?”

It was just bad luck Madame Richert, the flower shop’s pleasant owner, wasn’t there. “Something with a spring theme, but British. Or, maybe, a little…Irish.”

“Ah, Irish! We have les Cloches d’Irlande, not Irish, not in origine, but does zees matter? Your invités won’t know about flowers. And zey are perfect with ze lilies. I put zem with ze yellow, and zis is very spring, very élégant. It is what you want.”

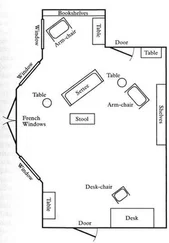

“It sounds lovely, Jean-Benoît.” She surveyed the rest of the shop. “All right, all right. We shall put them in the hall and the reception rooms. But, for the dinner table…”

“Ah, zere is a dinner, too. Why do you not say zis? You cannot have ze lilies for zis, zey are too tall, too… big. Too much parfum. ” He shook his head at her and clucked. “But, if one has primevères . Zis is very British, no?”

Primevères were primroses. Clare nodded. “Terrific. Thank you.” She leaned over a bunch of yellow freesia to drink in their heady tealike scent.

“Of course, zey will not last.”

“That’s all right. It’s just for this evening.”

Clare could hear his heels clicking as he headed back towards the shop counter. But he did make beautiful bouquets. She didn’t even have to ask what else he would add to them. After he’d finished painstakingly inscribing the order, she signed it.

“For sixteen ’our?” He handed her the order duplicate.

By 4:00 p.m., the table should be set. She would be at the hairdresser, but she could put out the vases before she left, and Amélie could place them about. Clare would have time for any necessary adjustments after she returned; she would not attend the cocktail party that would be held at the embassy before dinner. She and Edward had agreed upon this.

She nodded and folded the invoice away in her sweater pocket.

“Madame, do you know what ze primevère signify?”

Jean-Benoît’s particular passion, other than protecting the French language, was the perceived or historical meanings of flowers. Mme Richert had once confided in Clare that he was writing an entire book on the topic, a masterpiece, to be illustrated by a close friend, a very talented young artist. Clare had understood this meant his lover. Clare did not really wish to know, any more than she wanted to hear the presumed implication behind every bouquet or to read his masterpiece of a book someday. She used to like the look of a few sprigs of straw in an arrangement until Jean-Benoît had informed her it represented “a broken agreement.” She had never been able to use straw in a bouquet again.

“I don’t, but please tell me,” she said.

“Young love. I cannot live wiz-out you.” He spread his thin arms wide with a flourish before leaning forward to open the door for her.

Back on the street, the air was still filled with the scent of spring, so light and hopeful after the thick woodsy atmosphere inside the floral shop. April in Paris, this was the celebrated time for lovers in the City of Lights, when the gray drizzle of winter broke long enough to release the fragrance of the tiny green heads of new shoots on the plane and hazelnut trees, the wisteria starting to climb its loose-limbed way up the side of old stone buildings and cast-iron gates. In truth, what a blessing this posting in Paris had been for her, surrounded by art and the languages she loved. It wouldn’t be easy to leave, no matter where they were headed, even knowing an ambassadorship somewhere else less important would be a stepping stone necessary to holding the top rank back in Paris. Because, if everything went right, that could happen. Edward could end up eventually the British ambassador in Paris. He was on the right track for that.

Clare breathed deeply and took a few steps down the street.

A man planted himself in front of her, blocking her way. He pressed a folded sheet of paper into her palm.

“Madame,” he said in heavily accented English, his voice low and guttural.

She suppressed the urge to cry out in surprise; her free hand flew up in front of her mouth.

He leaned in closer, his legs split at shoulder width, thrusting out his elbows. There was something practiced about the way he stood, so firm and solid. His stance announced there would be no moving him; there would be no moving around him either.

Avoiding eye contact, she took the quick measure of him: dark, with an ashy colorless type of complexion — Albanian, at a guess — and the threat of black hairs about to burst forth from just-shaved skin. A slippery-looking leather jacket, much too hot for this warm April day, much too cheap for this fashionable street, and his respiration was labored. She could smell his body heat. She made a tentative motion to the left. He shadowed her shift in balance, a complicated pas de deux where neither of them moved more than an inch but he clarified that she would not step around him.

He was shorter than she was but wider, aggressively muscular. She glanced over his shoulder. A couple were crossing the road in their direction: young, dressed in pressed jeans and expensive loafers, deep in conversation. Students from the nearby Grande Ecole, Sciences Po. Words poured from their lips, words that she could not hear. One stopped to light a cigarette. They swung to the left when they reached the sidewalk and started down the Boulevard Raspail. A moment more and they were out of sight.

“Madame,” the stranger repeated. He pushed the piece of paper against her hand. She knew what might be written on it: Do not shout. Or: Do not try to run. Scaffolding swathed a building across the street. She scanned its metal web, but the workmen must have been on break, or on strike. She glanced around the empty street.

What had the U.S. done to Albania in recent weeks? Or could his nationality be something else? Iraqi, even? If it was that, what could anyone say?

Except…and a part of Clare flew up to view herself from afar, as though she were one of the pigeons roosting in a cote above. Or, better yet, an anger-filled terrorist hiding in a nearby car. There was nothing to indicate she was American. If anything, she could be taken for British. She had on flat Tod loafers, ecru woolen slacks, a cream-colored sweater set. The heavy silk scarf. Tall. No makeup. No hair spray.

Читать дальше