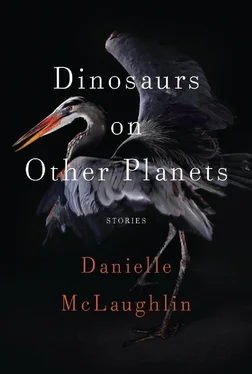

Danielle McLaughlin

Dinosaurs on Other Planets

Begin on the feast day of the goddess Guanyin, that she may grant mercy. Or on the cusp of winter when the cold will numb bones splintered like ice on a broken lake. Begin when she is young, when the bones are closer to water and a foot may be altered like the course of a mountain stream.

It is Tuesday and the woman who comes to clean has been in, leaving the hall smelling like the inside of a taxi, a synthetic pine fragrance called Alpine Spring, though it is the first week of November. Janice unbuttons her wet coat, hangs it on a peg. She has thought to mention that she dislikes the scent, but she and the cleaner rarely overlap, and, written down— I do not like the air freshener —the complaint seems trivial, almost petty. There is also the fact that the woman cleans for a number of other mothers at the school. Janice already senses a hierarchy of allegiances, suspects minor betrayals and indiscretions.

Music is coming from upstairs, a heavy thud of bass that vibrates through the ceiling: the sound of Becky skipping hockey practice. Mrs. Harding from next door will be around. She will have been sitting by her front window, watching for Janice’s return, and will now be struggling into her ankle-length fur, lacing up her shoes, ready for the assault on Janice’s front steps. She will complain how the wet leaves make them slippery, as if Janice has set a trap, and then, the music stopped, she will sit for an hour at the kitchen table, sniffing a cup of tea and talking.

As she climbs the stairs, Janice pauses on the half landing to rearrange the collection of crystals, miniature figurines of birds and animals. They are displayed on a table by the window where the light shows them to best advantage. Every Tuesday, the cleaner removes them to dust the table, and every Tuesday returns them in reverse order. Today, inexplicably, the table appears not to have been dusted, and still they are out of position.

In her daughter’s bedroom, a row of stuffed toys gazes from a shelf. The years haven’t been kind, each toy suffering its own peculiar disability: a ragged tailless Eeyore, a molting one-eyed teddy bear. Becky scowls when she sees her mother. “I told you to knock,” she says, switching off the music. She turned fourteen the previous July, and has suddenly grown taller and broader. Her face, already too round to be pretty, has become rounder, and she has taken to wearing her long brown hair, her best feature, in a tight bun. She is sitting on the bed, still in her school blouse and skirt. Her shoes and her gray woolen socks have been removed, and she is winding a pair of Janice’s tights around her right foot, the nylon already laddered where it stretches across her toes.

“What do you think you’re doing?” Janice says.

“Binding my feet.”

Janice watches her daughter attempt to curl her toes underneath her foot, watches them spring back up again. “You’re kidding, right?”

“It’s for a history project with Ms. Matthews. Basically, it’s about how women suffered long ago.”

“I still don’t understand why you’re binding your feet.”

“So I can em-pa-thize?” Becky says. “So I can see what it was like to be oppressed? Basically.”

“How old is Ms. Matthews?”

Becky doesn’t answer. She is winding the tights in a band around her toes. Just below her ankle is a silvery pink scar where she caught it in a door as a child, and the skin has grown back a shade lighter. She takes a strip of white material from a pile beside her on the bed and begins bandaging her foot, winding the cloth round and round, until the foot is a white stub.

Split the belly of a live calf and place her feet in the wound, deep, so that blood covers the ankles. If there is no calf, heat the blood of a monkey until it boils. Add mulberry root and tannin. Soak the feet until the skin is soft.

THE ROOM IS COLD, and Janice makes her way across the debris on the floor — underwear, magazines, aerosol canisters — to close the window. Tampons in brightly colored wrappers spill like sweets from a box on the dressing table, beside eye shadows and lip gloss. They seem out of place, these adult things, as if a child has been playing with the contents of her mother’s handbag. The bedroom is toward the back of the house and overlooks a narrow garden that slopes to the river. When Becky was small, Janice had worried that she would wander away and drown, and one summer Philip constructed a fence from sheets of metal nailed to wooden stakes. It has served its purpose but is an eyesore now, the metal sheeting buckled and rusted. Once spring arrives, Janice thinks, once the days are longer and the weather milder, she will dismantle it. She shuts the window and draws across the curtains.

Becky is still busy with the tights. Beside her on the bed are several sheets of paper, including one headed “The Art of Foot-Binding,” a poor-quality facsimile of a handwritten manual. Next to it is a page of photos and diagrams, some accompanied by instructions: Rub the feet with bian stone, or a piece of bull’s horn. Janice does not immediately recognize the thing in the photographs as a foot. It is a grayish-white lump, toes melted into the sole like plastic that has been left too near a fire. The owner of the foot smiles shyly out at the camera. There is something grotesque, almost sordid, in the way she displays her deformity, like a freak act from an old traveling circus, and Janice looks away, back to her daughter’s feet. As she watches Becky winding the strips round and round, she recognizes the delicate scalloping of the Egyptian cotton pillowcases from the guest bedroom.

“Damn it, Becky! Have you any idea how much those cost? Couldn’t you have used something else? Anything else?”

“I searched everywhere,” Becky says. “There was nothing else. If you were home, I could’ve asked you for something else, but you weren’t.”

“Maybe I should explain to Ms. Matthews the oppressive cost of pillowcases.”

Becky scowls, stops winding the bandages. “Why are you being such a bitch about Ms. Matthews?”

“Haven’t I told you not to use that word?”

“What word?”

“You know what word. And for the record, I’ve no problem with Ms. Matthews. I just think she’s got weird ideas about homework.”

“You hate her,” Becky says.

Janice takes a deep breath. “I don’t hate her,” she says slowly. “I’ve never even met her.” But as she says it, she remembers, from the open house two years previously, a slight red-haired woman with a choppy asymmetrical hairstyle and Ugg boots, though she had thought of her then as a girl because she was barely distinguishable from the gaggle of teenagers flocking around her.

“If you’d gone to the parent-teacher meeting you’d have met her. Dad met her. Dad likes her.”

Janice considers this, decides to let it go. She begins to pick up clothes from the floor and hang them in the wardrobe.

Becky continues bandaging her foot. “Ms. Roberts hates her, too,” she says, “but Ms. Roberts is jealous because Ms. Matthews is a dote and everybody thinks Ms. Roberts is a cunt. Which she is, basically.”

“Becky!” Janice stops gathering clothes. “You are never to say that word again. Do you hear me?”

“Ms. Matthews lets us say anything we like.”

“I’m warning you, Becky….” There comes then the sound she has been hoping for — the sound of the house phone ringing. “We’re not finished with this, Becky,” she says, wagging a finger at her daughter. “Not by a long shot.”

When the skin is smooth, break the four small toes below the second joint and fold them underneath. Take a knife and peel away the nails. They may creep like Mongolian death worms into the darkness of the heel and that way a foot may be lost.

Читать дальше