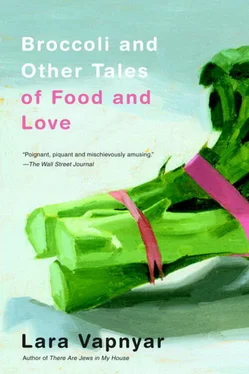

Afterward they ordered more gnocchi. The man moved his plate from the other side of the table to sit next to her. He sprinkled freshly grated Parmesan over her plate, refilled her glass, and entertained her with some silly stories of his childhood.

Ru  ena, suddenly ravenous, ate all of her gnocchi and then some from his plate.

ena, suddenly ravenous, ate all of her gnocchi and then some from his plate.

SIX DAYS LATERthey ate lunch in an Indian restaurant, where the booths resembled bamboo huts with straw mats for seats. They had been asked to leave their shoes outside the booth, and Ru  ena felt funny sitting barefoot in a restaurant. She smiled at her lover, who had been unusually silent at his friend’s apartment.

ena felt funny sitting barefoot in a restaurant. She smiled at her lover, who had been unusually silent at his friend’s apartment.

They were served bitter spinach puree, too spicy for Ru  ena. She’d said, “Mild, please,” when asked by the waiter, but apparently her voice had been too low. She was licking smidgens of spinach off the tines of her fork when the man spoke at last.

ena. She’d said, “Mild, please,” when asked by the waiter, but apparently her voice had been too low. She was licking smidgens of spinach off the tines of her fork when the man spoke at last.

“Ru  ena,” he said.

ena,” he said.

She’d never noticed how harsh her name sounded in English.

“Ru  ena, I can’t marry you.”

ena, I can’t marry you.”

The rest poured out in long, emotionally charged sentences. He wanted to be honest with her, he didn’t want to give her the wrong idea, his life was not going to change, he couldn’t allow their relationship to become too intimate, he couldn’t afford to have two women emotionally dependent on him. He was sorry, but he couldn’t marry her.

Ru  ena stared at her six-year-old boots on the floor next to the booth — their drooping tops, scuffed heels, toes scraped raw from a shoe polish brush. For once they weren’t hidden under the table but in plain view. She could feel burning spots blooming on her face and neck. Why was it that he assumed she wanted to marry him? Was it because of the breach in her careful detachment the last time, the hazardous leak of affection? Or perhaps there was another, more cynical reason for his assumption: It was natural for her — poor, lonely, and uprooted — to want to marry him — stable, successful, secure. The worst thing was that he might have been right. What if she did want to marry him? What if she did hope he would ditch his fiancée one day and marry her?

ena stared at her six-year-old boots on the floor next to the booth — their drooping tops, scuffed heels, toes scraped raw from a shoe polish brush. For once they weren’t hidden under the table but in plain view. She could feel burning spots blooming on her face and neck. Why was it that he assumed she wanted to marry him? Was it because of the breach in her careful detachment the last time, the hazardous leak of affection? Or perhaps there was another, more cynical reason for his assumption: It was natural for her — poor, lonely, and uprooted — to want to marry him — stable, successful, secure. The worst thing was that he might have been right. What if she did want to marry him? What if she did hope he would ditch his fiancée one day and marry her?

“Look, Ru  ena, I don’t want to hurt you. I really like you. I would have wanted very much to continue seeing you, if only we could find the right balance. You see, right now our relationship is out of balance.”

ena, I don’t want to hurt you. I really like you. I would have wanted very much to continue seeing you, if only we could find the right balance. You see, right now our relationship is out of balance.”

Ru  ena watched spoonfuls of spinach vanish in his roomy mouth while he talked. She’d felt that mouth on hers every week for several months. The wave of repulsion made her dizzy.

ena watched spoonfuls of spinach vanish in his roomy mouth while he talked. She’d felt that mouth on hers every week for several months. The wave of repulsion made her dizzy.

“Fuck you and your balance!” she wanted to yell. But instead of cursing his balance, she waited. The man chewed on a piece of naan.

“You don’t have to worry about balance. I have a fiancé too. I am sorry I didn’t mention him before; the right moment never came up.”

Ru  ena smiled. It was easier than she’d imagined. Her heart pounded, but that didn’t worry her. The heart wasn’t anything that people could see.

ena smiled. It was easier than she’d imagined. Her heart pounded, but that didn’t worry her. The heart wasn’t anything that people could see.

THE NEXT WEEK,over épinards à la crème , she told him her fiancé’s name was Pavel. They sat opposite each other in a small restaurant with wicker chairs, maps of France on the walls, and rude waitresses who spoke with an accent (Ru  ena wasn’t sure if it was French). The épinards à la crème, for some reason, was adorned with a fried egg.

ena wasn’t sure if it was French). The épinards à la crème, for some reason, was adorned with a fried egg.

“Pavel?” Her lover pierced the egg yolk with his fork. “ Pavel is a beautiful name.”

Ru  ena thought so too.

ena thought so too.

“What does he do?”

Pavel was a physicist. He’d graduated from Prague University and was offered a job in France. (For some reason the combination of physics and France thrilled Ru  ena.) He lived near Strasbourg, in a village at the crossing of two rivers, the names of which she had forgotten. Ru

ena.) He lived near Strasbourg, in a village at the crossing of two rivers, the names of which she had forgotten. Ru  ena was looking at a map behind the man’s back.

ena was looking at a map behind the man’s back.

It didn’t take a lot of effort to endow Pavel with a name, a profession, and a place of residence. All she had to do now was to add a few details, which turned out to be easy, even enjoyable.

All the men who used to be unattainable — her girlfriends’ boyfriends, college professors, movie actors, movie characters, dead writers, cousins, uncles — were now at her disposal, providing appearance and character traits, lifestyles, habits, even clothing patterns. How many times before had she wished that her boyfriend had one or another wonderful trait he lacked or had been spared the nasty one he possessed? Ru  ena felt as if the doors of a magic store were opened for her. She could roam between shelves, picking items she liked, refusing others. She chose her cousin Pavel’s name, Uncle Milan’s smile, her ophthalmologist’s beard, the heavy eyelids of her favorite Russian actor, and the aquiline nose of a French one. She selected the loose corduroy pants that her philosophy professor wore, and the plaid shirts favored by her first boyfriend, Zdenek. She spared her fiancé Uncle Milan’s schizophrenia, the Russian actor’s weak chin, and Zdenek’s habit of picking his nose while reading. She could have a man made to order.

ena felt as if the doors of a magic store were opened for her. She could roam between shelves, picking items she liked, refusing others. She chose her cousin Pavel’s name, Uncle Milan’s smile, her ophthalmologist’s beard, the heavy eyelids of her favorite Russian actor, and the aquiline nose of a French one. She selected the loose corduroy pants that her philosophy professor wore, and the plaid shirts favored by her first boyfriend, Zdenek. She spared her fiancé Uncle Milan’s schizophrenia, the Russian actor’s weak chin, and Zdenek’s habit of picking his nose while reading. She could have a man made to order.

Épinards à la crème tasted better than most of the spinach dishes she’d tried before. It wasn’t overdone, yet it didn’t have a grassy taste. She ate several large spoonfuls before answering more questions about Pavel. No, they didn’t mind the separation. It had been their choice to lead separate lives for some time before marriage. No, Pavel didn’t know about this particular lover, but they both had a realistic concept of “separate lives.”

The man had an attentive look on his face. He stopped eating and sat making holes in his spinach with the fork. There were yellow traces of egg yolk around his mouth. “Your Pavel sounds too perfect,” he said at last.

“Does he?” Ru  ena scraped the remains of creamed spinach off the bottom of her bowl. “Well, he is not.”

ena scraped the remains of creamed spinach off the bottom of her bowl. “Well, he is not.”

Ru  ena began granting her fiancé flaws. What started as a way of achieving authenticity soon turned into a source of pleasure. It was the imperfections — the awkward strokes of a paintbrush, tiny dabs of dirt, barely visible scratches on the canvas — that made Pavel lovable. Ru

ena began granting her fiancé flaws. What started as a way of achieving authenticity soon turned into a source of pleasure. It was the imperfections — the awkward strokes of a paintbrush, tiny dabs of dirt, barely visible scratches on the canvas — that made Pavel lovable. Ru  ena had to confine herself to granting Pavel only one fault at a time. Over German spinach salad with walnuts and apple bits, Pavel was given a gift of clumsiness. Over Mongolian spinach dumplings, he acquired slightly crooked front teeth. Over yet another dish of sautéed spinach, stubbornness. (By that time Ru

ena had to confine herself to granting Pavel only one fault at a time. Over German spinach salad with walnuts and apple bits, Pavel was given a gift of clumsiness. Over Mongolian spinach dumplings, he acquired slightly crooked front teeth. Over yet another dish of sautéed spinach, stubbornness. (By that time Ru  ena had become proficient at slicing spinach. It wasn’t tricky or sophisticated, as she’d thought before. It simply required some practice.)

ena had become proficient at slicing spinach. It wasn’t tricky or sophisticated, as she’d thought before. It simply required some practice.)

Читать дальше

ena, suddenly ravenous, ate all of her gnocchi and then some from his plate.

ena, suddenly ravenous, ate all of her gnocchi and then some from his plate.