(Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock )

…

Throughout their partnership, [Boileau and Narcejac] produced novels that were puzzles requiring close attention, each combining startling twists of plot with characters at their wit’s end, grasping at any opportunity to find meaning.

(Auiler, Vertigo )

…

Hitchcock: “[Music] makes it possible to express the unspoken. For instance, two people may be saying one thing and thinking something very different. Their looks match their words, not their thoughts. They may be talking politely and quietly, but there may be a storm coming. You cannot express the mood of the situation by word and photograph. But I think you could get at the underlying idea with the right background music.”

…

It could be said of me that in this book I have only made up a bunch of other men’s flowers, providing of my own only the string that ties them together.

(Michel de Montaigne, Essais )

…

An old thing becomes new if you detach it from what usually surrounds it.

(Bresson, Notes )

…

Research was Hitchcock’s detective work. He relished the process of ‘putting himself through it’ in preproduction, scouting out real-life settings and real-life counterparts for the characters. He compiled notes and sketches and photographs partly for authenticity. but also as a springboard for his imagination. He always tinkered with the reality.

(Patrick McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock )

…

Are the cameras shooting the footage for The Bridge sited at Old Fort Point? The very spot Madeleine chooses to jump into the Bay from?

…

At the beginning, I think of endings.

(Kate Zambreno, Heroines )

…

The only true purpose of a good list is to convey the idea of infinity and the vertigo of the etcetera .

(Umberto Eco, Confessions of a Young Novelist )

…

How should we understand Saul Bass’s spiral descending into the woman’s eye at the end of the title sequence? A hint of who will suffer — not Scottie — from the vertigo of the title? Or is it more surprising that, instead of descending into the woman’s eye, it doesn’t emanate out from it (as it does at the beginning of the sequence)?

…

Not the work I shall produce, but the real Me I shall achieve, that is the consideration.

(D. H. Lawrence)

…

There are people who like to complete all the reading, all the research, and then, when they have read everything that there is to read, when they have attained complete mastery of the material, then and only then do they sit down to write it up. Not me. Once I know enough about a subject to begin writing about it I lose interest in it immediately.

(Geoff Dyer, Out of Sheer Rage )

…

At the urging of my agent, I had been looking for a “more personal” response to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo for many months when, in September of 2012, Sight & Sound ’s decennial poll named it the best film of all time, forty votes ahead of Citizen Kane , which had held that title for fifty years. Suddenly, there were a hundred pitches for books about Vertigo , two hundred, more. I was relieved. As I say, I had been looking for an approach already for some time and finding that nearly every frame of the film had been pumped full of meaning and carefully explained by its critics again and again. What could I have added? Now, I could instead give up, remain silent.

I had been perfectly content to watch the film over and over, to read books about the film’s production, books of film theory and literary theory that mentioned it, biographies of Hitchcock, Novak, and Stewart — I had always been more of a reader than a writer. I copied out little snippets of interesting text, more notes than I ever would have read over, all without producing a single word of my own. In the margins, I wrote comments like this one, my lame attempts at the “personal” response my agent seemed to want but which never came together as a single story. I wondered, in an email to my agent (perhaps as a way of avoiding going through all of these notes and making something whole out of them, I emailed him, telling him I couldn’t get through all of my notes, couldn’t make something whole out of them) if this collection of quotes from other books and my marginal notes might not be a more convincing and ultimately more worthwhile book than the book they were intended to produce; it wouldn’t really be a personal response to the film, but I didn’t see that as a drawback. It would be a kind of critic’s notebook, an assemblage, a commonplace book, but also an homage and an acknowledgement. My agent replied that editors would be unmoved. He told me to get back to work.

He also told me I was being naïve. The only reason he had taken the book on was that it was sold already. It was a variable that was not a variable at all, a thing that could be counted upon. There would be people like me who would buy it, and there would be many people like me — just think of everyone who had seen Vertigo . I had only to “tell my part of the story,” like varnishing a chair from Ikea and telling people I had made it. As a result of the poll, though, other writers — more enterprising than I was and less bothered by the idea of “value”—were now picking up the subject. There would be ten new books on the film by the end of the year. The moment, he told me, would very soon pass, and every day I delayed, the book was less and less likely to garner any serious attention — by which he meant “sell well.” It would not make it to the shelves; it would begin and end in a bargain bin somewhere. This did not boost my confidence in what I was doing. I had already been wondering what I had to contribute to the study of Vertigo , and now I felt sure the answer was nothing.

…

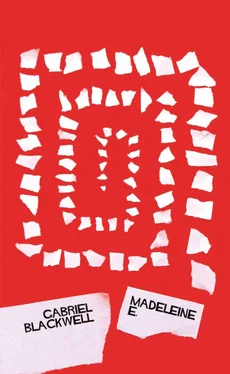

Madeleine E.

This is a book about a man and his girlfriend, who live together. She has taken a week off work, but doesn’t tell anyone why. She is going to have an abortion. She will need the rest of the week to recover. She would have taken more time off work, but she needs to work because the man is unemployed, and she supports them both, and she doesn’t make much to begin with. The man sits in the waiting room of the clinic with the girlfriend’s mother. The man feels as though something has caught up with him. He can’t imagine how things can get any worse, but he also can’t imagine that things will get better. He will always feel this wretched, he thinks. Nothing good will ever happen again. We do not learn what the mother or the girlfriend are thinking or feeling, but, really, what could be more difficult for either one than to find themselves in this situation?

As soon as the nurses have left her alone to rest, the girlfriend gets up from the operating table. She leaves the room she has had the procedure in and goes across the hall to where she left her clothes. She dresses and walks out into the waiting room. Alright, she says, let’s go. It has all been so quick, the nurses haven’t even noticed she’s not in the operating room anymore. The man and the mother don’t know the girlfriend isn’t supposed to be up and moving. The girlfriend faints on her way to the elevators, even while being held up by the man and her mother, and she sits on the floor next to the elevator for half an hour before she can finally make it downstairs and into the car. The man feels guilty about the whole thing. Not what happened after, but what happened before. Even though it was a decision they both made, he feels responsible. He even feels guilty about feeling responsible; it’s self-centered, he thinks. The last thing he would ever do is address the subject head-on. He avoids talking about it and tries to avoid even thinking about it. Forever after, the man can’t imagine the child that might have been, but he never forgets that it doesn’t exist. They never speak about it.

Читать дальше