…

It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real, that is to say of an operation of deterring every real process via its operational double, a programmatic, metastable, perfectly descriptive machine that offers all the signs of the real and short-circuits all its vicissitudes.

(Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation )

…

Again, though, there may be three parts to the movie, not two. Not just before the staged death and after, but before Scottie’s acrophobia, during it, and after his “cure”; what Scottie believes is happening (the “front” story), what is really happening (what “the audience is looking at”), and something that cannot be defined (“ ”) but which must have something to do with Scottie’s life before his accident. Or with Judy’s.

…

People need to feel that they have been thwarted by circumstances from pursuing the life which, had they led it, they would not have wanted; whereas the life they really want is precisely a compound of all those thwarting circumstances. It is a very elaborate, extremely simple procedure, arranging this web of self-deceit: contriving to convince yourself that you were prevented from doing what you wanted. Most people don’t want what they want: people want to be prevented, restricted.

(Dyer, Rage )

…

The actress took the limitations of her costume as a source of character development: “I can use that feeling when I play Judy. Judy is trapped into portraying Madeleine, and she doesn’t want to. She wants to be loved as Judy. But she always has to go along with what someone else wants in order to get the love she wants. So I used that feeling of wearing someone else’s shoes that didn’t feel right, that made me feel out of place. The same thing with Madeleine’s gray suit, which made me stand so straight and erect the way Edith Head built it. I hated that silly suit, to tell you the truth, but it helped me to be uncomfortable as Madeleine.”

(Auiler, Vertigo )

…

It is an odd thing, but everyone who disappears is said to be seen at San Francisco. It must be a delightful city, and possess all the attractions of the next world.

(Wilde, Gray )

…

According to Hitchcock’s biographer Patrick McGilligan, the sequence of Scottie following Madeleine was originally accompanied by a voice-over. It must have been Scottie’s narration — who else could it belong to? — but, since he knows nothing about Madeleine or what she’s up to in these scenes, and since he must come across as mystified so that we, the audience, will know that we should be mystified, I can’t imagine what he would have said. “Well, now, I wonder what she’s doing here.” Having that voice-over would put the audience in Scottie’s head, making the picture that much more subjective, so the fact that it has been cut from the film as it was eventually released must mean that we are not meant to be in his head, that we should be further removed from the events we see onscreen than Scottie is. We are not meant to empathize with him, but still we feel what he feels sympathetically because he is the film’s focal point, and because while we cannot understand Madeleine — who, after all, doesn’t exist to be understood — we can understand Scottie.

…

I can’t find any evidence of this voice-over in the script, but in the version posted on dailyscript.com (accessed 7/22/12), there is a voice-over — Elster’s — in the Ernie’s scene. Elster’s monologue continues from the office scene to the restaurant: “I don’t know what happened that day: where she went, what she saw, what she did. But on that day, the search was ended. She had found what she was looking for, she had come home. And something in the city possessed her.”

…

Elster yearns for the past and fears it.

…

It always surprises me when a commentator remarks upon Judy as Elster’s mistress. I see no evidence for it in the film.

…

[INT. Flower Shop (DAY)]

…

Does Madeleine seem to be turned away from Scottie because she is shown in a mirror (and so reversed, as in a negative)? Or is she actually facing away from him?

…

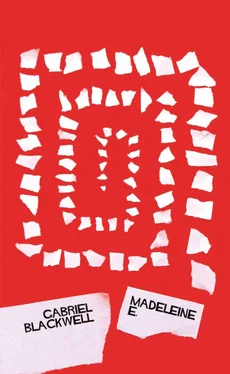

I was either bored or I was obsessed. I don’t have enough distance from myself to be able to say. I scrolled through hundreds of pages of search results for “Gabriel Blackwell,” thinking maybe, eventually, I’d come to the end. There, buried deep in all those virtual mes, were ads for “Background Reports,” people promising to continue my search in the real world. How could I resist?

The first service that had me in its database was named “personsmart.com”; all I could see without ordering their report were the cities and states where I had lived, my age, my immediate family members, and any aliases I had used (I hadn’t used any, but the listings around mine all had several, a fact I found intriguing). Their information was accurate, but they had my age wrong — they thought I was two years older than I was — and they thought I still lived in New Orleans, even though I had moved away in 2005 and had lived in three places in Portland in the meantime. For $27.95 (discounted 30 % with “membership trail” (sic, I think — they had to mean “membership trial,” as appropriate as “trail” is)), personsmart.com would send me a report listing my: “age, possible current address, up to 20 year address history, phone numbers, bankruptcies, tax liens & judgments, property ownership, possible relatives, possible roommates, aliases / maiden names, neighbors, marriages and divorces, dea registrants, nationwide criminal check and website ownership.” Even though I was curious about the difference in age, I couldn’t justify spending thirty dollars to have someone tell me things I already knew. Half of the things they offered to tell me about myself had nothing to do with me anyway.

But when I clicked back to the Google search results page and tried the next link (there were results from “stillman.com” and “america-person-search.com,” among many others), I found the same info, the same weird age mistake, and another address, one that did not correspond to any city I had ever lived in, in San Francisco. San Francisco? Surely this was a joke.

…

There are. times. when the performance of a conscious self-imitation, or anti-Method acting, comes in very handy. A person who has undergone a trauma. may experience it like a death, so that she feels as if she had become a different person and tries to keep going by pretending to be who she was, trying to behave as she knows she used to behave, until she can remember how it actually feels to be who she is.

(Doniger, The Woman )

…

Does one ever resemble oneself?

(Villiers de L’Isle Adam, Tomorrow’s Eve )

…

Ecstasy. literally means being beside oneself, which means standing slightly apart from one’s body and slightly apart from one’s mind. From which vantage point one might experience one’s body — and perhaps even one’s consciousness — as things.

(Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty )

…

You put on a bishop’s robe and miter, he pondered, and walk around in that, and people bow and genuflect and like that, and try to kiss your ring, if not your ass, and pretty soon, you’re a bishop. So to speak. What is identity? he asked himself. Where does the act end? Nobody knows.

(Philip K. Dick, A Scanner Darkly )

…

In this film in which we have a man (Gavin Elster) playing himself but not himself (since not only is he innocent in his version of himself, but he is also concerned for his wife’s health and safety in that version of himself) and a woman (Judy Barton) playing another woman (Madeleine Elster) who is supposed to be playing a third woman (Carlotta Valdes), it seems notable that the only character whose identity can actually be said to have really changed during the film is the one who seems most himself throughout: Scottie Ferguson.

Читать дальше