I remember the night at the end of November when the radio announced that in America the United Nations, at a place called Lake Success, had decided to let us set up a Hebrew State, albeit a very small state divided into three blocks. Father came home at one o'clock in the morning from Dr. Buster's, where they had all gathered to hear what the radio said about the result of the vote at the UN, and he bent over and stroked my face with his warm hand:

"Wake up. Don't sleep."

With these words he lifted up my sheet and got into bed next to me fully dressed (he who always insisted so strictly that one must not get into bed in day clothes). He lay in silence for a few minutes, still stroking my face, and I hardly dared to breathe, and all of a sudden he started to talk about things that had never been mentioned in our home before, because it was forbidden, things that I had always known one mustn't ask about and that was that. You couldn't ask him, you couldn't ask my mother, and in general there were a lot of subjects about which the less said the better, and there was an end to it. In a voice of darkness he told me about how it was when he and Mother lived next door to each other as children in a small town in Poland. How the ruffians who lived in the same block abused them, and beat them savagely because the Jews were all rich, idle, and crafty. And how once they stripped him naked in class, at the Gymnasium, by force, in front of the girls, in front of Mother, to make fun of his circumcision. And his own father, Grandpa that is, one of the grandparents that Hitler later murdered, came in a suit and a silk tie to complain to the headmaster, but, as he was leaving, the hoodlums grabbed him and forcibly undressed him, too, in the classroom in front of the girls. And still in a voice of darkness Father said this to me:

"But from now on there will be a Hebrew State." And suddenly he hugged me, not gently but almost violently. In the dark my hand hit his high brow, and instead of his glasses my fingers found his tears. I never saw my father cry, either before that night or since. In fact, I didn't even see him then, only my left hand saw.

Such is our story: it comes from darkness, wanders around, and returns to darkness. It leaves behind a memory combining pain and some laughter, regret, wonderment. The kerosene cart went past in the mornings, the kerosene seller sitting on top with the reins hanging slackly in his hands, ringing his handbell and singing a long-drawn-out song in Yiddish to his old horse. The boy who helped at the Sinopsky Brothers grocery had a strange cat that followed him everywhere and wouldn't let him out of its sight. Mr. Lazarus, the tailor from Berlin, a nodding, blinking man, shook his head in disbelief: who ever heard of a faithful cat? He said: Perhaps it is a Geist, a spirit. The unmarried doctor Magda Gryphius fell in love with an Armenian poet, and followed him to Famagusta in Cyprus. A few years later she returned, bringing with her a flute, and sometimes I would wake up in the night and hear it and a kind of inner whisper said to me, Never forget this, this is the heart of the matter, everything else is only a shadow.

And what is the opposite of what has really happened?

My mother used to say: "The opposite of what has happened is what has not happened."

And Father: "The opposite of what has happened is what is going to happen."

Once, when we bumped into each other in a little fish restaurant in Tiberias, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, some fourteen years later, I asked Yardena. Instead of answering me, she burst into her luminous laughter, that laugh that belongs to girls who enjoy being girls and who know pretty well what is possible and what is doomed. Lighting a cigarette, she replied: "The opposite of what has happened is what might have happened if it weren't for lies and fear."

These words of hers took me back to the end of that summer, to the sound of her clarinet, to Chita's two fathers, who went on living there after his mother died, to Mr. Lazarus, who raised hens on the roof and a few years later decided to remarry, made himself a dark-blue three-piece suit, and invited us all to a vegetarian meal, but that evening, after the wedding and the reception, suddenly jumped off the roof, and to PC 4479, and the panther in the basement, and Ben Hur and the rocket we never sent to London, and also the blue shutter which may be floating on the stream to this day on its circular journey back to the mill. What is the connection? It is hard to say. And what about the story itself? Have I betrayed them all again by telling the story? Or is it the other way around: would I have betrayed them if I had not told it?

1994–1995

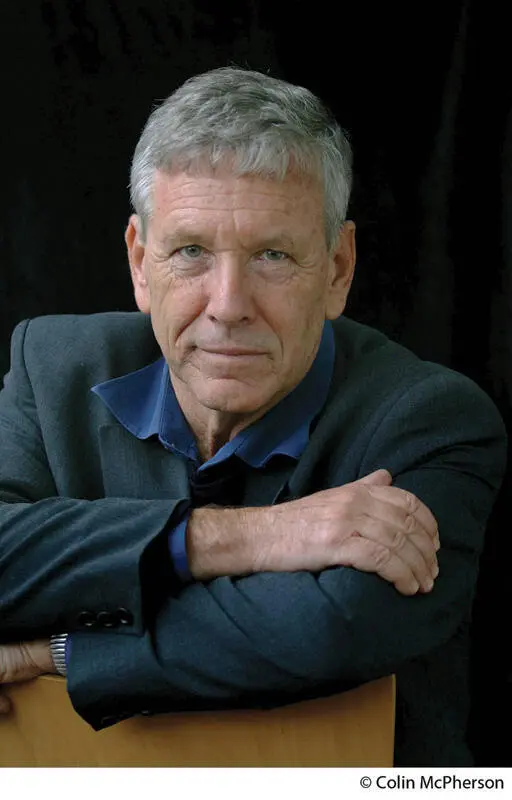

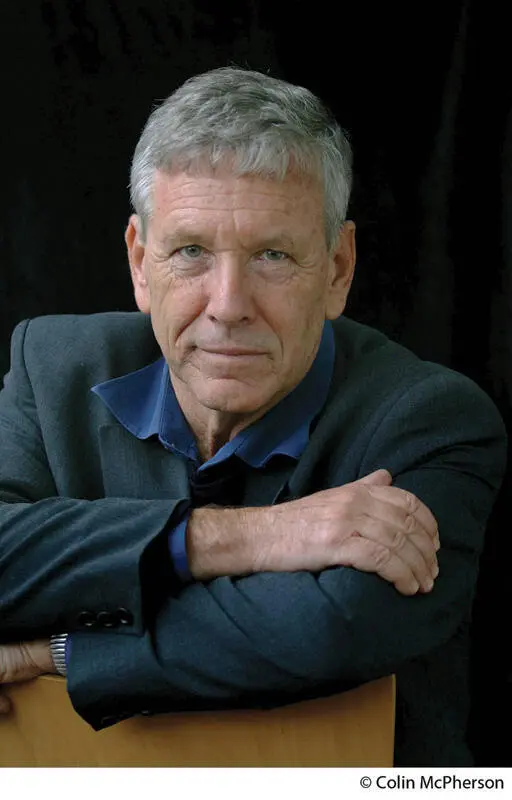

Born in Jerusalem in 1939, AMOS OZ is the author of numerous works of fiction and essays. His international awards include the Prix Femina, the Israel Prize, and the Frankfurt Peace Prize, and his books have been translated into more than thirty languages. He lives in Israel.