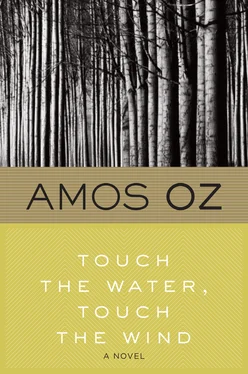

Professor Zaicek said to Stefa:

"It is my duty to speak to him. The situation must be clarified. You must invite him here one day, Stefa my dear, for a talk, for tea, so that we can demand an explanation."

Stefa said:

"That would be a terrible risk. Even your papers are not your own."

The old man reflected, and admitted the fact For a while he absently stroked one of the Siamese cats, then he leaned back and continued gently stroking the arm of his chair. How he wanted not to sound melodramatic, yet to use words that Stefa would never be able to forget, even in her dreams. Finally he spoke:

"But Stefa. Surely. We didn't run away to the forest, did we? And why did we both refuse to run away? Surely, dearest Stefa, it was because the word danger has no external validity. We have taught time and again, and recently we have even committed it to print, that the real danger is always from within. And have we the right, my wonderful Stefa, to turn our backs on our own teaching? Surely there are moments in the life of an individual or of a people when silence is an abhorrent misuse of speech. No, Stefa, no, my dear, no, here we are and here we stand and we cannot be otherwise. In the face of evil, we must stand up and say: evil! Now it's time for tea."

Primly but eagerly, almost gaily, Stefa clapped her hands, only the corners of her mouth betraying a new determination.

'Yes, teatime, my dear Professor; I am sure you have been waiting for your tea. Won't you take your place at the head of the table; here comes your napkin, and your teaspoon, and here's the samovar."

She tied the napkin round his neck to protect his brown jacket, put his teaspoon in his hand, deftly removed a silver hair from his shoulder, poured two cups of tea, and nodded to Professor Zaicek to give the sign.

The sage asked in vain for butter: times were not easy. So he gave the sign for them to start, took a hesitant sip, and said:

"Kindly put on the light. And in the study too. After tea I want to dictate a letter to Martin Heidegger. His position is a great mystery to me. I deliberately refrain from saying a disappointment. A Socratic letter. That is to say, I shall put a few questions to him. Questions and nothing more. Yes, Stefa, of course I shall lower my voice as you request, but I shall not stop talking. As for compromises, my dear, you and I could both get up tomorrow morning and leave for America or Palestine as if to say that evil disgusts us but is none of our business. But that is not what we have taught, that is not what we have written, that is not what we have determined. It is madness to think of evil as the private affair of the evil man, just as hunger is not the private affair of the starving man or disease that of the invalid, nor is death the problem of the dead, but of the living, and that means us, my one and only Stefa. The thermometer fell again today, and apparently therefore it is getting colder. You ought to devote a moment's thought to Martin Luther. Luther was vulgar and ignorant, and yet he offers us a surprisingly clever way out of the moral dilemma. But should we, my Stefa, casually take this cheap way out? No, Stefa, no, my dear, we shall hold fast to our course even in the midst of this great darkness. There's that glass tinkling again in the street — in the garden — as if all of a sudden there are pieces of glass hanging from the branches of the trees and the wind makes them tinkle. What is it, Stefa, what does the tinkling signify, if indeed it signifies anything at all?"

Stefa said:

"I can't hear any tinkling. The windows are closed and shuttered. There's nothing there."

The Karl Marx face, furrowed by wisdom and agony, seemed to brighten and darken and brighten again in the flickering light, and the warm voice spread through the room as if seeking the darkness beyond the shuttered windows. How can he, thought Stefa, how can he ask me to put on all the lights. Now. These are almost the last days. There is no more time.

In that instant a tortured, emaciated form floated soundlessly into the room, grinning from ear to ear, the drunken gardener who was nicknamed Run-Jesus. He bowed twice, first to his master and mistress and then to the wall, perhaps to the stuffed bear's head. He laid some damp logs in the grate, grinned another depraved grin, displaying his rotting teeth, and exacted his wages and the price of his silence from Stefa. Suddenly he began to plead, with short sharp sobs and hoarse coughs, sounds which resembled the barking of a fox:

"Multiplying beyond all bounds, they are. No one to keep an eye on them, that's what. Like bedbugs they're spreading. Millions of them. Laughing they are, too, the dogs' blood. What's so funny here, eh? Won't be long before we'll all have to sleep standing up, won't even have room to lie down at night. There's a thousand of 'em born every minute. And as soon as they're born they start breeding. Into their own mothers' wombs, the sons of bitches. And how they breed. Like a plague. Holy Mary forgive me for what I'm saying. Is there enough water for us and for them, eh? No, there's not. Dogs' blood, there's not. Look at me, now, I'm a sick man, sick through and through, my poor legs, and then there's the coughing, and what's more I'm a sinner, but don't I deserve a drop of water same as anyone else? Millions of 'em. More and more born every minute, some says a thousand, some says more, church mice can't hold a light to 'em. And what's the upshot? Millions of them'll die of thirst. Not enough water. Not enough room to stand up in, even. Not enough air to breathe. And on Tuesday I brought you eggs and potatoes, and if God Almighty wills it, there'll be feathers, too. Not to mention the flour. And suppose the river dries up, what'll they drink then, eh? And that lot'll breathe up all the air too, and we'll all suffocate, grrr, like leprous dogs. It's cold tonight, good Sir and Madam, it's very cold, very very cold. Jesus guard me from this cold. Me, I'm a sick man, a coughing man, and I'll tell you a secret, I'm dogs' blood too. But Jesus won't laugh at me. It's stupid for us to laugh, good Sir and Madam, stupid, sinful, indecent, nothing to laugh at here while that lot, curse 'em, breed and breed without a moment's pause. Christ's blessing on you both."

Furiously poised on the sideboard stood a carved African warrior covered in war paint. Day and night the savage threatened the terrified girl in the Matisse painting with his huge, grotesque manhood. And from above, the bear's head, amazingly silent, looked down.

The glass eyes reflected the candlelight and shot back flashing sparks.

Once again the tranquillity of dark forests. The night wind's caress. The silent frost. The squelching mud. Flight without escape. If you strike with all your might, the ax will break.

Beneath the crust of ice lurk different forces, far from the nature of ice and far from peace and rest. Powerful forces which cannot be exorcised by formulae or incantations. Even music gradually abandons you night by night and flows into the night and with the powers of night it grinds its teeth at you.

Deep in the evil Polish forest deep in the heart of the darkness deep in the womb of the soggy undergrowth can be seen shadows of giant creepers clasping and choking the dead tree trunks with silent fury as though squeezing the last drops from a desperate loving embrace.

And the wide wastes resound with the frantic howling of wolves.

Pomeranz had suddenly had enough.

He was tired of wandering, tired of peasants, of Germans, of the soughing fir trees, of fleeing like a sick animal.

And the snow and the fire and the wind.

So he played his mouth organ at them with all his might and main, until the Russians heard and burst across all the rivers in their way, San, Bug, Wisla.

Читать дальше

![Хироми Каваками - Strange Weather in Tokyo [= The Briefcase]](/books/29150/hiromi-kavakami-strange-weather-in-tokyo-the-br-thumb.webp)