Mikhail Andreitch, with a look of stupid panic on his thirsty face, his grin broadening to that of a terrified cat, his teeth short and white:

"Don't, Comrade Fedoseyeva, please don't, you know that kind of talk won't help either of us, the past is all behind us now and our faces are turned to the future. Look, I am thinking, I'm thinking quickly and thoroughly. I'm thinking full steam ahead, if there is such an expression."

"And your conclusion, my dear Stakhanovich? "

"Conclusion. Yes, conclusion. Where could we be without conclusions. Well, yes. Palestine it is, Comrade Fedoseyeva: I'm ready to pack my bags and go, if those are your orders. I'll go anywhere you like without a murmur. But still, Palestine is a rather unimportant spot. And tiny. A kind of temporary refugee camp that our Jews have set up among the sand dunes and holy ruins. They're still trying to get their bearings, everything there is still in a confused, experimental stage."

Fedoseyeva:

'That will do, Andreitch. It's not for theoretical arguments that I've been raising you here. Shut up, my peerless Andreitch. Shut up in Russian. Just make yourself a note: Palestine. You ought to be glad; I was certain you'd be writhing with joy. Palestine is full of nuns of every shape and size. But just you keep your hands off them. You can feast your eyes on them to your heart's content, but kindly keep your filthy paws to yourself. By the way. I suppose you've got some good men there who know a thing or two?"

"Yes, Comrade Fedoseyeva, I have indeed. And they're always complaining. They complain about the climate, they complain about the boredom, the language, and the flies. After all, it — how should I say — it isn't a very big place."

"That's enough, Andreitch, you've said quite enough already. Now go and change, pack your overnight bag, and off you fly. Wait a minute."

"Yes. Right away."

"Stand still and stop jumping up and down. Now listen carefully. Apart from the nuns, the music there, I hear, is of the highest quality. Concerts, symphonies, Jews playing and singing with gusto-you won't be at a loss in Palestine. Prick your ears up, Andreitch. There's something in the air. You know better than anyone my sudden flashes of intuition. So don't fall asleep, Mikhail Andreitch. Things happen in Palestine."

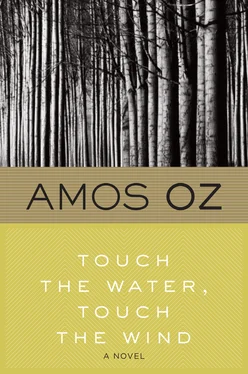

Elisha Pomeranz led a quiet life.

Sometimes in the evenings he fell prey to hesitations, and he, in his usual patient way, almost loved this moment. The burial of the last light of day. Noman and silence upon the broad lawns. Noman in the gardens. Among the lilacs. The woods empty and shadow-soaked. A faint breeze blowing off the hills, touching the pines with its fingertips, coaxing them, spreading amazing rumors, whispering high limpid forgiveness. The breeze inspired the pines with a powerful quiet hallucination which was almost more than they could bear. Then, holding his breath, he could see with his own eyes the pine trees in the darkness stretching upward to the very bounds of music.

Afterward, by the light of mathematical theory or astronomical calculations: the intricate powers of circularity, radiating bodies in dark space, the opposing energies coursing between the bodies in curves which cannot be perceived by the senses, only by an abstract intention, until the intention suddenly casts doubt, almost ridicule, on the material objects round about. The shelf and its shadow. The desk. The lamp and its pool of yellow light. The paper. The pen. The rustling of the paper. His writing hand. The smell of his body. His body. His breath. The absurd connection between his calculations and the network of white threads, gray fluids, moisture, what a ridiculous connection. And so humiliating.

In short, the dreamy son of a watchmaker rendered unto the kibbutz those things which belonged to the kibbutz, and when he had completed all his labors he always closed himself up in his room and his silence.

The kibbutz, however, went on living its rhythmical life: day succeeded day, and the intervening nights were suppressed, because night always seems to be full of malign intentions and so it must be uncompromisingly shut out or cautiously circumvented. No alternative. Indeed, here among the rocky Galilean hills, where thorns flourished even on bare rocks, the nights certainly betrayed a threatening, simian quality.

Day succeeded day, and by seven o'clock white non-light already beat down on roofs and treetops, scorching concrete paths, dominating deserted lawns, blazing on tiles and corrugated iron. The tyrannical light painted sharp clear circles round every enclave of shadow. Just so far. The frontiers of shade. Blue light. Line. White light. Line. Blue-white light. Square-cut hedges, neat rows of trees, tidy lawns, all speaking an unambiguous language. Climb the mountains, crush the plain, All you see — possess it. The tractor shed here, the dining hall there, and the recreation hall plugging the valley with its low, broad bulk. We are here. Guarding order. Darkness to expel.

Various suspicions were leveled at Pomeranz:

His peculiar indifference to the customary ideals.

His avoidance of all organized activities.

His lackadaisical attitude toward the betterment of Society and the Individual.

He doesn't read the evening paper even when you ram it under his nose.

He never makes suggestions.

Never criticizes.

You can never tell, with him.

Thinking. Who knows what.

So withdrawn.

How come?

The pupils he coached in the evenings said:

"His room is always clean and spotless. It's a mania with him, tidiness. Whenever you try to sit down, he adjusts the angle of the chair to the table. If you accidentally kick up the corner of the rug, he goes down on all fours at once, like a long thin dog, and straightens it under your feet."

"He keeps the lights dim, and there's always coffee and flowers in the room, and also a sort of faint smell everywhere which isn't the smell of the flowers or the smell of the coffee and you really can't tell what it is. Perhaps not a smell at all. Something. The air is different in his room."

"As if he's always expecting a special visitor."

"And that silence. Even when he talks to you, it's as if he's talking in silence."

"He's not all there. A bit gaga."

"It can't go on. There's something strange about him, something lonely, how to put it, weird, it might be dangerous or something. Almost. Something might happen one day, all of a sudden. We ought to do something about him. Before it's too late."

"And that dog. It's not a dog-it's a ghost."

"It's frightening."

So too, each evening, sitting on green benches under the lilac trees ot on the edge of the lawn on deck chairs, the old women knitted Pomeranz. Wondering. Comparing. Remembering things that had happened and phrases from lectures or from the newspapers. Exchanging views and rumors. Pausing on a significant detail. Energetically well-meaning. Muttering a special salvation for him. A solution. Something.

Moreover, his name was included on the agenda of one of the kibbutz committees, a discreet item. Nothing urgent, though, nothing that couldn't be postponed.

Among themselves the other sheep farmers sometimes nicknamed Elisha Pomeranz "the Wizard." But the sheep, as ever, as in bygone days, since time immemorial, silently went on dreaming.

Soon or late, one clear pale night, Elisha Pomeranz arose and went down to the faraway waters to the thicket and the reeds to Emanuel Zaicek's hiding place. He barely touched the ground as he went. He wore his pointed hat and his red boots, and his ax was tucked in his broad sash.

And when the two watchmakers' sons met on the bank of the stream they did not speak words or compare ideas or try to formulate a letter or a manifesto. For a while they both played the same Jewish melody on two different instruments; then they exchanged instruments and tried another similar melody. There was no breeze. The night was silent.

Читать дальше

![Хироми Каваками - Strange Weather in Tokyo [= The Briefcase]](/books/29150/hiromi-kavakami-strange-weather-in-tokyo-the-br-thumb.webp)