“Just one,” she says. “He’d be perfect.”

I toss the rag toward the door and yell for Jake. He freezes in his tracks at the edge of the store lot. I jog across the gravel and say to him in a low voice, “That lady wants to take your picture.”

He looks at me with fear in his eyes, and then shoots a quick glance back at the California people. “I didn’t do nothing,” he says. His voice is shaky. Tobacco juice has stained his gray chin whiskers brown.

I see the round bulge of something in his pocket, and I figure he’s probably got me for another can of pork and beans. “I know that,” I say. “It’s just what she does, Jake. She takes pictures of people.”

He shakes his head. “I don’t like that, Hank,” he says. Then he starts off again. It’s the first time in all these years I’ve ever heard him say my name.

I walk back over to the woman. By the look on her face, I can tell she’s disappointed. “I didn’t figure he’d do it,” I say.

She shrugs, takes a photo of Jake’s backside, and then turns to me. “What about you?” she asks. “Just a couple of pictures underneath that sign?” She steps a little closer and I get a faint whiff of her perfume. A trickle of sweat runs down her neck, and disappears beneath her silky blouse.

I look up and down the road, but I don’t see any cars coming. The holler’s dead, everything in it hypnotized by the noonday heat. “I don’t know,” I say. “I ain’t much for pictures either.” The last time I had one taken was in high school, right before the old man died. We drove into Meade on a Saturday, and he bought me a white shirt and one of those little clip-on ties at Elberfelds. All the way home he kept teasing me about looking like a preacher boy. That was the last good day we ever had together.

“Please?” the woman says.

Though I wish these people would just leave, I can’t refuse the lady. “All right,” I say, “if you hurry. I got work to do.”

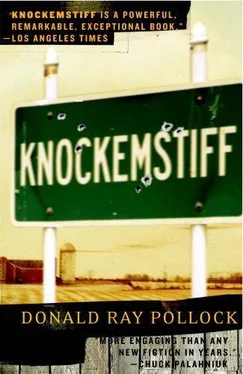

“It won’t take but a minute,” she says. We walk out to the sign by the edge of the road. She tells me exactly where to stand, and then she moves away a few feet. I see Jake glance back at us, and then slow down a little bit. Behind me, I hear a car coming. I turn and see Boo Nesser’s green Ford pop up over the hill. “Christ,” I say to myself, looking back at the woman, hoping she’ll speed things up a little bit. But the car pulls up fast beside me and squeals to a stop on the asphalt. I stare straight ahead. “Okay,” the woman says. “Say Knockemstiff .”

“What?” I say. I push the hair out of my eyes. Standing in the sun, I’m starting to sweat out last night’s Blue Ribbon, and I worry about the smell.

“She wants you to say Knockemstiff , you dumb shit,” Boo says. He’s got a red bandanna wrapped around his head, a little feather sticking up in the back. His head is hanging out the window, his big teeth as yellow as dandelion blooms in the bright light. Three or four big cardboard boxes are strapped to the top of the car with baling wire and rope. A table lamp is standing up in the backseat. Everything he and Tina own in the world, I think. Boo flicks a cigarette butt at me and laughs when I jump back. Though I won’t go so far as to say I hate him, I guess I wouldn’t mind if he dropped over dead right now.

“You know, like instead of cheese ,” the woman says. “Just try it.”

“Okay,” I say. Then I hear a door open on the Ford and Tina runs around the car and hops in the grass beside me. The girl doesn’t have a backward bone in her body. She’s wearing a tight pair of cutoff jeans and a baggy T-shirt she bought two weeks ago at the county fair for a dollar that says DO UNTO YOUR NEIGHBOR, THEN SPLIT. I know everything about her, and I wonder how long it will take me to forget that. “Do you care if I get in on this?” she asks the woman. “This might be my last chance to get my picture took with a dumb hillbilly.” She smells like bacon grease and Ivory soap.

“Your last chance?” the woman says, looking up from the viewfinder. “What do you mean by that?” Her voice sounds a little aggravated at first, but then I see her look down at Tina’s dirty bare feet and smile.

“Because me and Boo’s headed for Texas,” Tina says, “and we ain’t coming back.” Her arm brushes against mine, and I feel a jolt like electricity. “Ain’t that right, baby?” My heart starts beating faster.

“That’s right, sweetie,” Boo says. Then he shuts the engine off. “We done outta this fuckin’ place,” he whoops.

The woman gives a little laugh and glances over at her husband. I turn and look, too. He’s leaning against the car, his eyes fixed on Tina’s ass. “Well, I sure don’t blame you for that,” the woman says to Boo, flashing him a smile. She raises the camera again and steadies herself. “Okay, ready? Say Knockemstiff .”

“Knockemstiff!” Tina yells, so loud it seems to echo off the hills. Then she turns and punches me hard in the arm. “Come on, Hank, goddamn it, you didn’t even try.”

“All right,” I say and nod at the camera. “One more time.” Then we say it together — Knockemstiff — and it almost sounds like it means something. The woman squats down and shoots a couple more pictures. Tina giggles, and I try my best to smile, but my face can’t seem to manage that right now. As I stand there, next to the woman that I covet, my head buzzes with all the things I want to tell her before she leaves, but I don’t say a word. I might as well be out following my old man’s ghost around in that orchard, afraid to kill a rabbit. And then I hear Boo yell, “Come on, Tina, it’s time to go,” and I can’t even say good-bye. Instead, I lean back against one of the signposts and watch Jake’s gray head start to sink over the other side of the hill.

That same night, at nine o’clock sharp, I take the money out of the cash register and stick it in the box. I figure I took in over a hundred dollars since morning. Maude never did come around, never even called on the phone to see how I was doing, and it’s been another long fucking day. I sit out back beside my camper and watch the green hills slowly disappear as the last of the light fades away. After a while, I take my shoes off and pop a Blue Ribbon, light a cigarette.

Down the road Clarence starts up the same shit again with his old lady, and I wonder where Tina is tonight. I think about us putting on a show out front today for that California woman, and all those photographs that she took. I turn the beer up and suck the suds out of it, toss the empty over in the pile. Right before she left, the woman tried to hand me a couple dollars for my trouble, but instead I asked her to send me one of those pictures. “One with me and the girl,” I told her, and she promised that she would. When it comes, I’ll stick it up in the store through the day so that people can see it. And at night, I’ll take it down.

WHEN PEOPLE IN TOWN SAID INBRED, WHAT THEY REALLY meant was lonely. Daniel liked to pretend that anyway. He needed the long hair. Without it, he was nothing but a creepy country stooge from Knockemstiff, Ohio — old-people glasses and acne sprouts and a bony chicken chest. You ever try to be someone like that? When you’re fourteen, it’s worse than being dead. And so when the old man sawed off Daniel’s hair with a butcher knife, the same one his mom used to slice rings of red bologna and scrape the pig’s jowl, he might as well have cut the boy’s ugly head off, too.

The old man had caught Daniel playing Romeo in the smokehouse with Lucy, Daniel’s little sister’s carnival doll. Daniel was giving it to her good, making believe she was Gloria Hamlin, a snotty, bucktoothed cheerleader who’d spit chocolate milk on him last year in the school cafeteria. “Boy, that’s Mary’s doll,” the old man said when he jerked the smokehouse door open. He said it matter-of-factly, like he was just telling his son that the radio was calling for rain, that the price of hogs was down again.

Читать дальше