Through the thin walls, I heard Mary tell her bedridden husband, “No, he ain’t up yet.” Ever since Sandy brought me home with her one night last fall, I’d been helping take care of Albert. Each morning, before Mary would crack his first fifth of wine, I’d go in and shave the old man, scrub him off, change his diaper. It all came down to a matter of timing. If Albert didn’t get his breakfast by ten o’clock, he’d start seeing dead soldiers hanging from parachutes in the apple tree outside his window. This meant getting up early, but I kept thinking that if I did right by the old man, maybe somebody would return the favor someday. I rose up and looked at the clock on the dresser.

Pulling on my jeans, I glanced down at some of Sandy’s pencil drawings scattered on the floor. She was always working on a picture of the Ideal Boyfriend. Sometimes she’d fire up some ice and lock herself in the room, stay revved up for two or three nights practicing different body parts. Reams of her fantasy were slid under the bed. Not a damn one of those pictures looked like me, and I suppose I should have been grateful for that. Every one of them had the same tiny head, the same cannonball shoulders. Eventually, she’d crawl out of the room with blisters on her fingers from squeezing the pencil, scabs around her mouth from smoking the shit.

Albert started smacking his flaky white lips as soon as I entered the room. Except for a constant tremor in his left hand, he was dead as Jesus from the chest down. Mary had already retreated to the living room, but she’d put out a dishpan of warm water and a thin towel on the stand next to the hospital bed. A can of Gillette and a straight razor sat on top of the dresser. I lathered him up and lit a cigarette to steady my nerves. I studied the map of veins on his purple nose while he grinned at me through the foam.

Just as I began scraping his neck, Mary rushed through the door with a fifth of Wild Irish Rose. Albert’s head started trembling as soon as his yellow eyes zoomed in on the wine. “It’s nearly ten, Tom,” Mary panted. “You about done?”

“Almost,” I answered, flicking some ashes on the floor. “Maybe you oughta go ahead and give him a hit. He gets to bouncin’ around, I might cut him.”

Mary shook her head. “Not ’til ten o’clock,” she said adamantly. “We start that, it’ll just get earlier and earlier. He runs me ragged as it is.”

“I still gotta change him, though,” I said, pressing my palm against his sweaty forehead to keep him still. “What about his medication? Maybe you ought to try it sometime.”

“This is his medication,” Mary said, waving the bottle around. “Lord, he wouldn’t last a day without it.” There was a drawer full of pills in the nightstand, but in all the months I’d been staying there, I was the only one who took anything his doctor had prescribed.

I finished the shave job, then wiped Albert’s face with a damp washcloth, ran a comb through his brittle gray hair. Pulling down the scratchy blankets, I said, “You ready, pardner?” His face twisted as he tried to spit out a few garbled words, and then he gave up and nodded his head. The old man hated me changing him, but it was better than lying in his squirts all day. I unfastened the paper diaper and took a deep breath, then raised his bony legs up with one hand and pulled it out from under him. It was soaked with brown goo. I dropped it in the wastebasket, wiped his ass with the washcloth. Then I taped a new diaper on him from the box of Adult Pampers lying on the floor. By the time I had him fixed up, he was bawling again.

As soon as I tucked the blankets back up around him, Mary broke the seal on the bottle and handed it to me. I jabbed one end of a straw down the neck of the jug, slipped the other end in Albert’s mouth. The clock on the wall said 9:56. Four more minutes and he would have been back in Korea. I held the fifth and smoked another cigarette while the old man sucked down his morning oats. Sandy’s high, whiny voice traveled down the hallway into the sickroom. She was singing her song about a blue bird that wanted to be a red bird. “Where’d you two go last night?” Mary asked.

“Hap’s,” I said, dabbing at a trickle of wine running off Albert’s chin.

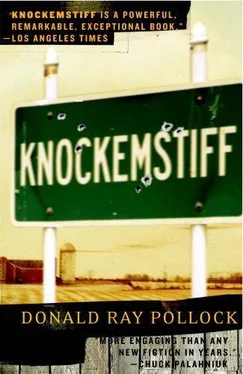

“I should have figured,” she said, and left the room. Other than Hap’s Bar, the only other business that was still hanging on in Knockemstiff was Maude Speakman’s store. Even the church had fallen on tough times. Nobody had loyalty anymore. Everyone wanted to work in town and make the big money at the paper mill or the plastics factory. They preferred doing their shopping and praying in Meade because the prices were lower and the churches were bigger. I figured it was only a matter of time before Hap Collins sold his liquor license to the highest bidder and closed up the only good thing still left in the holler.

After Albert nodded off, I killed the inch of dregs he’d left in the bottle, then went out to the kitchen and poured a cup of coffee. From the back window, I could see all the way across Knockemstiff. It had snowed a bit during the night, and smoke rose from the chimneys of the shotgun houses and rust-streaked trailers scattered along the gravel road below. A chain saw started up somewhere over Slate Hill. I ate a piece of cold toast while watching Porter Watson fill his truck with gas at Maude’s, then stumble across the parking lot in all his camouflage padding and go inside the store.

Looking across to the other end of the holler, I could just make out the frosted nose of the Owl’s car sticking out of the hillside across from Hap’s Bar. It was an abandoned 1966 Chrysler Newport, but people around here called it the Owl’s ride, the Owl’s castle, the Owl’s this and that. Nothing was known about the car’s original owner, but Porter Watson made sure nobody in the fucking county ever forgot the screech owl that had roosted in the front seat the summer after the car, plates missing and engine busted, mysteriously appeared parked halfway up the hill. You’d have thought they were cousins the way Porter went on about that stupid bird.

I rinsed my cup and walked into the living room, eased myself down into the saggy couch. Scenic vistas torn from old calendars were pinned to the walls, looking like windows into other worlds. Triple A guidebooks were scattered everywhere. Though Mary had never owned a car, she had a book for every state. She was always pretending a trip somewhere.

“She’s nuts,” Sandy had told me the first night I went home with her. We’d just knocked one off and were lying in bed drinking our last quart of beer. “She laid a goddamn rock on my bed the other morning, claimed she’d found it at the Grand Canyon. Kept blowing off she wanted to bring me home something special.”

“So?” I’d said.

“So? I’d just watched her pick it up out of the driveway. Hell, that old bitch ain’t never been out of the state of Ohio, Tom.”

I kept my mouth shut, sucked down the suds in the bottom of the bottle. My wife had finally kicked me out, and I was desperate for a place to stay.

“Besides,” Sandy said, getting up and heading for the bathroom, “what kind of present is an old dirty rock anyways?”

…..

WE WATCHED THE TUBE ALL THAT WINTER DAY, SMOKING cigarettes and drinking weak coffee and eating cheese crackers from a box. With the house sitting on top of the knob like it did, the TV could pull in four channels, so there was always something to watch. Still, there were times I wished they had cable. During the commercials, Sandy worked on another drawing of the Ideal Boyfriend, and Mary flipped through a book about Florida. Every so often I’d get up and check on Albert, give him another straw of wine to keep the war away.

Читать дальше