The Minister of Agriculture, Industry, Commerce and Estates: Anastase Stolojan

The Minister of Public Works: Ion I. C. Brătianu

Afterword: A Thing of Beauty by Mircea Cărtărescu

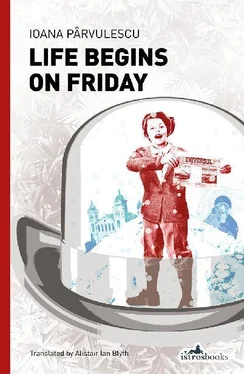

If the novel Life Begins on Friday seems an unusual text to the foreign reader, it will not be because of any cultural differences: Ioana Pârvulescu’s book is unusual even in the context of today’s Romanian literature. It is a singular book, which with intelligence and talent defies the current directions of Romanian prose. It has nothing to do with the problematics of the communist regime, the Ceaușescu period and the Securitate, or with the violent, pornographic sound and fury of punk anarchism, or with postmodern re-visitation of historicized artistic styles, or with the minimalistic depiction of everyday life. It is not an ideological text, does not fight on any front, and does not claim to hold any indubitable truth.

It is merely what we like to call a thing of beauty , far from the cacophonous din of all battles. It is a book of delicate nostalgia for times less brutal than those of today, and also a book consummately skilled in reconstructing, with infinite detail and infinite patience, an epoch from which we are separated by more than a century. Like a children’s pop-up book from whose pages spring three-dimensional palaces and people, Life Begins on Friday is a multi-dimensional scale model of the city of Bucharest in the closing years of the nineteenth century, with its topoi and typical inhabitants. But it is a scale model that will soon seem to us disturbingly real.

Published in 2009, the novel was a surprise for the majority of Ioana Pârvulescu’s readers. Her previous books, which had grown increasingly visible and admired in Romanian culture, were mostly non-fiction. In the last decade, the author, an admired literary critic and historian, professor in the University of Bucharest, published, among numerous studies about the hotspots of Romanian cultural history, two veritable bestsellers. Both are affective reconstructions of past epochs, which employ the tools of both the historian and the writer. The first is Return to Inter-bellum Bucharest , the second The Private Life of the Nineteenth Century . Although the author’s undoubted literary talent was immediately remarked upon in the cultural press, the books won multiple awards and were admired above all as histories of cultural ideas. Few could have predicted that their author would next take the step towards total fictionalization.

However, this step was implicit in her previous books. In fact, both books were backdrops for a novel that was merely awaiting fictional characters. For, they were already brimming with characters imbued with a real historical existence: writers, journalists, physicians, lawyers, as well as their wives and children, comprising a vast social fabric, the inhabitants of a different century, one unfamiliar to us. They would continue to live in Life Begins on Friday , but the same as in Doctorow’s Ragtime or in certain novels by Pynchon, their lives were here to be intertwined with those of imaginary beings, although no less vivid and interesting for all that.

Having honed her skill at minutely describing period settings, the author moved on to a novel, a true novel, with a serious and complex plot structure. The book tells the story of the last thirteen days of the year 1897 in Bucharest, in thirteen polyphonic chapters, each chapter having multiple narrative voices. In each chapter, the different characters alternate in having their say, each viewing the same events from different perspectives, as we also find in Agatha Christie’s Five Little Pigs , for example, although this does not necessarily lead to an elucidation of the events in question.

The name of the famous author of detective novels is by no means out of place in the present discussion. The most obvious connexion with Ioana Pârvulescu’s novel is that it employs the structure of a detective novel. From the very first pages a double mystery takes shape, which will subsequently lead to two different but always interwoven levels of the book: a coachman finds two bodies lying in the road at the edge of town. One is still alive and will become the central enigma of the book; the other will turn out to have been shot and dies in hospital soon thereafter, but not before uttering a mysterious string of words. According to the typical pattern, we also have a detective, in the person of Costache, the Chief of Public Security. The book’s two strands, one fantastical, the other to do with the detective novel, form a counterpoint and pick up speed before racing towards a shared finale.

The fantasy theme follows the Caspar Hauser archetype: the young Dan Krețu wakes up to find himself in an unfamiliar world, in a Bucharest of the past. He is an alien to everybody, dressed strangely and looking unlike ordinary people. He seems to be the inhabitant of a different world and each of the characters has a different theory about him. Throughout the novel he moves like a sleepwalker among the other characters, bewildered by the huge change that has befallen him, but also enchanted by the world in which he now finds himself: a Bucharest that is different and nonetheless the same as the one that he senses, but is not certain he knew in his other life. Like his illustrious literary predecessor, Poor Dionis, who sprang from the magnificent imagination of Mihai Eminescu, Dan Krețu meditates on the mystery of time, on the fact that past and future are simultaneous with the present. The finale has a big surprise in store for the reader attentive to this theme.

The detective plot provides the bones of the novel, whose soul is the fantastical and metaphysical theme. Its backdrop is a series of interconnected historical occurrences, the kind of sensational events that have always been the preserve of the tabloid press. Some of these events were of international renown: Jack the Ripper and the Dreyfus affair. Others relate to Bucharest life: a duel in which a leading journalist is slain by an equally famous politician, as well as various spectacular thefts. Colourful thieves, greedy aristocrats, fraudsters, and policemen who are now solemn, now ridiculous are all caught up in a complicated plot, full of quid pro quos and confusion: objects crop up, are interchanged, and then vanish in highly synchronized order.

In addition to the two interwoven major themes, what fleshes out the novel and anchors it in reality (albeit a poetic and illusory reality) is the sweeping panorama of everyday life in the Bucharest of yester-year. Throughout the novel the author follows a number of narrative threads to do with typical city places: the Universul newspaper offices, the family home of the respected Dr Margulis, the Prefecture of Police, the hospital, the public baths, and finally the aristocratic mansion where the characters come together to spend New Year’s Eve. In this socially stratified world, perhaps the strongest voice of the novel is that of Iulia, the doctor’s daughter, who with grace and maturity records in her diary the astonishing events that turn the peaceful lives of her friends and family upside down. Iulia’s diary is the book’s sounding box, the place where each theme acquires affective coloratura. Here too there takes shape a delicate love story, on which Iulia meditates with unexpected lucidity. The model of the romantic girl had passed, and something in Iulia’s thought and behaviour anticipates the emancipation of women that was to take place two or three decades later.

A number of other characters prove to be priceless narrative aids to the author as her description of Bucharest takes shape, characters sketched with the assurance of a Balzac or a Hugo: Costache, the chief of police, is a middle-aged philanderer haunted by nostalgia. Newspaper boy Nicu, aged just eight, is an extremely likeable little Gavroche, who with his every appearance brings a ray of sunlight to the novel, a ficelle character involved in untangling (and tangling) the novel’s threads. He has access to the slums and the down-trodden, the poor part of Bucharest, which could not be left out of the novel’s landscape.

Читать дальше