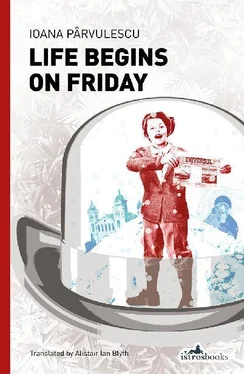

‘The usual untruths from Adevĕrul !’

Procopiu and Pavel Mirto had made their way to the newspaper offices through the blizzard and were planning in broad outline the New Year issue. They were plucking up courage with the help of tea laced with rum. Pavel, whose spectacles were steamed up, warmed his hands on the porcelain tea cup, while Neculai Procopiu warmed himself by reciting from the rival gazette. Although the editor-in-chief had quoted the passage to Pavel only to make fun of their counterparts in Strada Sărindar, he was still a little envious when he thought of them. The article was unsigned, but it seemed to be in the style of Constantin Mille: expressive distortions of reality, beautifully turned phrases, well-honed rhetoric, that of a former professor of literature who had become a lawyer. Overlaying it all was his militant socialism, which was the reason he had been expelled from the University of Jassy many years previously and which, rather than subsiding, was all the more aggressive. And of course Alexandru Beldiman, the newspaper’s founder, had been the first to lavish streams of inky bile on King Carol and the heir to the throne, Prince Ferdinand, endlessly repeating like a bird of ill omen that the latter would not reign even for a day. But on the subject of the truth, it ought to be known that a large number of streets had been paved, and the money for Brătianu’s statue did not come from the pockets or ‘stockings’ of the Town Hall, but had been raised by means of tombola draws. A large part of the money from the New Year grand lottery, to whose result Procopiu was by no means indifferent, was earmarked for various municipal works. As for Mr Mille, everybody knew that he had bought shares in the newspaper with funds that were suspect to say the least. He now used Adevĕrul to thrash the King black and blue, although the King did not care to react, or refrained from doing so, since as everybody knows that press has become the Fourth Estate throughout the world.

‘I wouldn’t be surprised if years from now, with the collectivists in power and the King banished, there will be people who do not know or do not want to know the truth, and they will name a street after Mille. Perhaps right here, on Strada Sărindar,’ said Pavel in a whisper. Thereupon, he lit a cigar.

Procopiu was accustomed to such original and gloomy ideas: one of his colleague’s obsessions was the future, and now that he was writing a novel about it, he seemed almost not to live in the present any longer. And Pavel’s future was radically different from all the futures of his friends and acquaintances. Procopiu had told him many times, albeit in vain, to get married, and that he would see life and the future in a different light, which was his own experience. Ever since he became a married man, it was as if his thoughts had been tidier, just as his wife’s hand made sure the house was tidy, although she did nag him rather a lot. But on the other hand, the most senior newspaperman at Universul was afraid of Pavel’s predictions. At least when it came to elections, Pavel’s predictions were always systematically borne out. He thought for a moment about the future and, for the first time, he was afraid.

Lately old man Cercel’s belly had been behaving like an animal, giving him certain signals, and he spoke to it like he spoke to his doves. For example, that morning, when he woke up, his belly immediately began to squeak, and he said to it: ‘So you’re awake too, are you?’ He said it aloud, and so his wife answered drily: ‘For ages! I get up before you every morning.’ A short while later, Cercel said to his restless belly: ‘Come on then, little dove, let’s eat!’ and his wife thought he was talking to her, much to her amazement. Now, at work, his belly was annoyed, probably at having to brave the blizzard and go to work on a Sunday, and it stabbed him maliciously, as if it had knives inside, and to placate it, he said: ‘Behave, this is what it’s always like before New Year, but after that we’ll have some time off.’ Nevertheless, all was not well with his belly. Should he nip over to Dr Margulis’ surgery? But then he would have to get somebody to stand in for him. Surely half an hour wouldn’t make any difference… Undecided, the doorman picked up a newspaper at random, from the pile that had arrived from other editorial offices, but on seeing that it was L’Indépendance Roumaine , he put it back. With his belly in the state it was, he did not feel like deciphering the Gazette of the late Lahovary, and to tell the truth, there was no much he could decipher. Old man Cercel knew a bit of French, but only enough to be able to communicate when a foreigner came through the door of Universul , but reading it was a different kettle of fish. He picked up the next newspaper, which happened to be Lumea Nouă . He grimaced and put that one back, too. It was one of those papers that had socialist ideas. Up until two years ago, their neighbour Constantin Mille had been in charge of it, and even now they kept attacking Nicu Filipescu, saying he was worse than a common criminal, because he killed openly and in the presence of witnesses! The doorman respected the former mayor and liked the fact that he was an active young man. Nor did he feel like reading Românul or Drapelul , and Adevĕrul even less so. Adevĕrul was the paper that annoyed him the most. Timpul was too dull and didn’t have the wit it used to have in the old days, when the men with the biggest brains in Bucharest wrote for it. In fact, without Nicu, whom he kept up to date on what the papers were saying, he didn’t much feel like reading any of them.

‘Speak of the devil, I was just thinking about you. But what’s up with you? What happened?’ he asked, taking fright, when he saw the boy, completely white from the blizzard and carrying a bird cage with a very distressed Speckle inside.

Nicu looked as bedraggled as the bird, his eyebrows joined in the middle like an arrowhead, and despite the cold outside his cheeks were chalky white.

‘She doesn’t like it at my house, she doesn’t love me, I love her. I thinks she’s sick, she misses her house!’

He rattled off the words one after the other without a pause.

‘Sit down and catch your breath.’

The doorman opened the door to the cage, held Speckle beneath her wings, felt her and turned her on every side.

‘I think she hasn’t been eating,’ he said, and the lad confirmed that she had neither eaten nor drunk, but she had left droppings, as was visible. She had left droppings all over the house, because he had let her out of the cage, and then he had struggled for a long time to put her back in.

The doorman decided to take her back and in spring to give him a pair, but only after he built a coop for them. You don’t keep a dove in a cage, like a parrot or a canary, because you’ll kill it like that. Seeing the state the lad was in, he decided to read to him from Universul and looked for a story of love with obstacles, because Nicu listened to those attentively: ‘The flight of a young lady from Vaslui : Love has no boundaries and neither the laws of the world nor of religion can stop its adventurous flight. Proof of this is what happened a few days ago in Vaslui…’ As old man Cercel’s voice unravelled the tangled plot, the boy’s face grew calm and took on colour, and the melted snowflakes caused his cheeks to glow. Finally, when he saw that nothing could stop the two young people ‘of different religions’ and that the girl’s relatives ‘will finally be convinced that they can not easily shatter the strong chains of love,’ he felt as if he were one of the bird’s relatives and he no longer felt sorry for sending her back to her mate.

Читать дальше