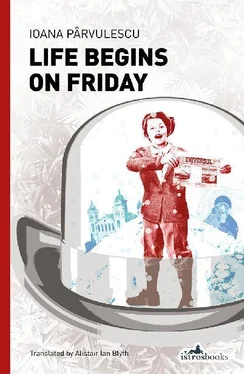

He took a pile of old magazines and newspapers and began to flick through them, wetting his finger on his tongue, reading an article here and there in the light of the lamp, aimlessly, although somehow he lingered over all the news items connected to the ex-mayor Filipescu. This was a public figure that had preoccupied him for a long time, and he had remarked that his haughty and determined gaze in a way resembled his Borzoi, but sometimes he had less brains than the hound. After leafing through a few calendars, particularly those that had historical headings, he picked up the 3 September 1893 edition of Universul . ‘On Monday a tender for the demolition of the Sărindar Church was held at the Ministry of Religions. The demolition was awarded for the price of three thousand, five hundred lei. The work must be completed within a month.’ This had certainly not done Filipescu’s reputation any good. Although at the end of this century the people of Bucharest thought less and less about things holy, compared with folk from the beginning of the century, and although many, including himself, declared themselves atheists, their heaven was not altogether empty and at a pinch they were capable of remembering that man was as insignificant as a worm. At the time, Nicu Filipescu was thirty-years-old, and had been Mayor of the Capital for around half a year and was determined to do great things. And since Sărindar had been abandoned, rather than seeking to repair it, he decided to demolish it. He was, let us admit, justified in a small way: ever since two spires had been added inappropriately, the building had been a public menace. On top of which, the General remembered that rats and dead cats had been the only adornment of the churchyard, which looked worse than a patch of waste ground. But it was in that church that a large number of Bucharest’s leading citizens had been married, and others, less fortunate, had set out thence on their final journeys. And so the demolition wounded many memories.

Nicu Filipescu was one of those young men who believed it was better to demolish what tottered rather than waste time consolidating and salvaging it. He had brought in convicts to do the job, since nobody else wanted to damage a holy place. The effect on the people of Bucharest was worse than could have been foreseen: the elderly came weeping and asking to be given at least a brick to take home, to guard them against evil. Strangely, now that it no longer existed, Sărindar looked better in the eyes of Bucharest’s inhabitants than it had when it still stood. But was it not the same for him, the General, now that his beloved wife was no more? Now, she was always there with him. The General moved on to the news items about duels, a subject of great controversy. Yet he felt it to be true that honour had to ben defended, and he did not agree that two men who fought in a duel mutually agreed upon and in the presence of witnesses could be considered ‘common criminals’: the law proposed by Viișoreanu was intolerable! But nevertheless, he felt sorry for Lahovary, the man had the courage of an entire army. It was a pity that he had not had time to train; the general himself could have taught him, given ten days of serious training…

Even before the electric doorbell shattered the silence, Lord had pricked up his ears. He then sped to the door like a cannonball, barking deafeningly. At the door was an unknown woman of around sixty, modestly dressed, who alighted from a luxurious carriage that had pulled up to the entrance. The General was struck by the woman’s aquiline nose and the stony expression on her face such as only his best soldiers could manage. He invited her into the salon, bringing the dog to heel with difficulty. The guest was not intimidated by Lord, however, and seemed not even to notice the poor dog.

‘I have sent you countless visiting cards and since you did not reply, I decided to break the rule,’ said the lady with the faintest of smiles. ‘Look, here is the last one,’ said the guest, discovering a visiting card on the tray by the door. The General held it at a distance from his eyes and read: Mrs Elena Dr Turnescu . He could not imagine to what he owed the honour of her visit.

‘I cannot imagine to what I owe the honour of this visit, Madam Dr Turnescu, or rather the joy of this visit. I know you by your reputation.’

‘I have an important matter to communicate to you. I know that you were the Prefect of Police, and my husband spoke of you with respect.’

And without further ado, in words sparse and clear, she told him the reason for her coming.

The street was deserted and the air brisk. Fane the Ringster trod softly, with the gait of a wild animal. He suspected that they had not released him for nothing. Of course, they never had any evidence against him, because he worked cleanly, as he himself was in the habit of boasting. The real reason had to be the stranger’s safe. They probably hoped that by following him they would find it, whereas if he was locked up it didn’t profit them at all, and besides, it only gave them an extra mouth to feed.

‘Leave it to me, Jean,’ said Fane by way of farewell to the unfortunates who were spending their Christmas in the cells, ‘I weren’t born yesterday!’

As he walked along the street, he gave a whistle of amazement when he found a barber’s shop open. He stepped over the broom shank, which propped open the door, and flung himself down on a wooden chair in front of the mirror. Everything was going like clockwork; he would be dapper when he visited his ‘fiancée’.

‘What’s this, Jean, open on a holiday, you’re not a Turk, by any chance, are you?’

‘My name’s Mitică — Dumitru that is, not Jean, Jean is a barber on Strada Măgureanu, as far as I know,’ said the barber and then started talking about politics, unions and the barbers’ refusing to have a day off during the holidays. The truth was that the Government had rejected their request and ruled that the barbers’ shops should close, but a few of them, including him, had broken the law. What could happen, after all?

The customer chided him: ‘Shut your trap, you’re sending me to sleep.’ And indeed, his eyes, the colour of Quetsch plums, were on the point of closing.

Fane was above social disputes, because he had his own politics, and was his own master. The barber admired his moustache, offering to trim it according to the latest fashion, which dispensed with such long fringes.

‘Trim it, and trim that tongue of yours with that there razor while you’re at it,’ said Fane gently, and the barber gave a rather horsey laugh. Perhaps it wasn’t such a good idea to open on a holiday after all; all kinds of dubious characters turned up. He began to hum softly, so as not to be obliged to talk, and dipped the shaving brush in the lather. Then he lathered the customer’s cheeks nicely, taking especial care to avoid his moustache. He trimmed his hair and then massaged his scalp with eau de cologne, causing Fane to grunt with pleasure.

After he left Mitică’s shop, trimmed, shaved and perfumed, Fane checked to see whether he still had a police tail and then decided it wouldn’t look amiss if he went to a public bath, and so he headed in the direction of Grivița Avenue, to Vasiliu the pharmacist’s establishment. This time he was going for a reason that nobody else must suspect. But he was out of luck: the establishment was closed and locked. He chewed his moustache and swore so loudly that even his tail must have heard him. But you never know what luck has in store for you and it seems that somebody within had heard him or perhaps seen him, because with his ear finely tuned to certain sounds he heard a key turning in the lock. The door opened and in the crack appeared a tousled young head.

Читать дальше