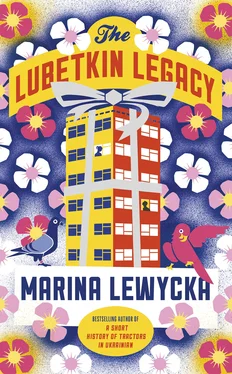

I crossed the cherry grove and hit the lift button to carry me up to my home on the fifth floor, before spotting the Lift Out of Order notice. Again. Madeley Court, the 1952 local authority housing block where I lived with Mum, had definitely seen better days. The paintwork was shabby and the concrete surfaces were discoloured. Even the name-sign had been vandalised many years ago by a friend of my half-brother Howard, a kid called Nige, who had an exceptional head for heights and a long rope he had filched from the tarpaulin of a lorry he was robbing. He had prised away some of the ornate terracotta tiles, and the missing letters had never been replaced, leaving just: MAD Y URT. Mad Yurt. The name seemed apt.

‘One day he’ll fall! Splat! Brains spread all over the pavement. If he’s got any brains!’ raved Mrs Crazy from the balcony of her flat directly below ours, who had narrowly missed being hit by the falling L.

‘Shut up! Stop your shouting!’ Mother shouted down at full volume from our balcony. ‘You’re lowering the tone around here. It used to be decent before you moved in, Crazy! You think wearing a big cross on your neck makes you holy. Well, it don’t! It makes you a bigot!’

Mrs Crazy, whose real name was Mrs Cracey, was the widow of a former East End evangelical minister undone by gambling and alcohol. She and Mum enjoyed that particularly venomous enmity reserved for people who have once been close friends. As the oldest resident, in both senses, Mum felt her status entitled her to respect. Mrs Cracey, a retired dental secretary some ten years younger than Mother, flaunted godliness and social superiority, which after her husband’s death from liver failure gradually drifted away from the evangelical and towards the High Church, as evidenced by her purple coat, mitre-like hairstyle conserved under a shower cap, and her penchant for jewellery, including the inevitable flashy gold cross on a chain around her neck. She patronised Lily as a lower-class upstart and a godforsaken communist.

‘I’ve had more communists than you’ve had hot dinners!’ was Mum’s oblique retort as she flicked a long finger of ash over the balcony, the gold and diamonds on her fingers glinting in the sun. She too was not averse to a bit of bling.

That was my first inkling that the community spirit of our block was provisional and mutable, despite the revolutionary intention of the architect Berthold Lubetkin to design solidarity into the structure of the estate.

Berthold Lubetkin, after whom I was named, was either an old flame of Mother’s or a celebrated Russian modernist architect, depending on whom you chose to believe. According to her, Lubetkin’s company Tecton had been responsible for the finest post-war public housing in London, and it was a sodding shame that he was best known for the penguin pool at London Zoo. When the sherry sweetened her memory she would sometimes drop hints about a secret love affair with Lubetkin, and weepily confess that it was thanks to him that she came to occupy this prime penthouse flat in the flagship Tecton development.

In an alternative version of the story, Lubetkin was born in Georgia, and Mother got her flat thanks to Ted Madeley, who sat on the Council’s Housing Committee alongside the legendary Alderman Harold Riley, who had first commissioned Lubetkin. Riley was a passionate socialist but not much of a looker. Lily admired him, but fell for handsome already-married Ted Madeley. She lived with Ted out of wedlock at first, a shocking enough deed at the time, then she married him, thereby acquiring the tenancy of this desirable flat. After Ted died, she had married twice more and raised two children here (though only I was hers by birth — the other was my half-brother, Howard, my father’s son from a previous marriage, of whom more later).

‘So it serves them right!’ she would declare. ‘They’ and ‘Them’ were shape-shifters who featured large in Mother’s demonology.

The spacious and sunny top-floor flat in Madeley Court which had been my childhood home later became my sanctuary, when my life fell apart and I needed somewhere to go to ground. As a child I’d taken for granted the two generous-sized bedrooms and small study, the comfortable old-fashioned kitchen and the square book-lined living room; but its special surprise, which even as a kid I had appreciated, was the south-facing balcony where Flossie the parrot was put out in her cage on summer mornings to sun herself, and where the impulse-bought barbecue rusted drowsily under the red dome of its lid. In front of the flats was a fenced area of communal garden which we called the grove, where cherry blossom flowered, toddlers played on swings, old folks cultivated dahlias in raised beds, and where Howard, my louche half-brother, snogged the local schoolgirls, weather permitting. Idyllic would be too strong a word, but it was all perfectly pleasant. Even the vandalism was minimal.

Neighbours had come and gone; the flats which had been built to rehouse the poor from the slums of the East End now housed a global community who lived together in relative harmony, though without the same intimacy as the original East Enders. I had never got to know the seven foreign students crammed into the flat next door where the dustman Eric Perkins had once lived — they changed every year. But there were people who still recognised me and greeted me when I went out, which made it feel like home.

Now some swivel-eyed politician, of whom Mrs Penny was the local instrument, wanted to take it all away, and cast me out into the unknown. A bedsit in Balham? Or Bradford? I’d already experienced the transience and insecurity of the private rented sector. It nearly did for me. Why couldn’t they just leave me alone? What I’d almost forgotten, before Mrs Penny reminded me, was that for several years, while Howard had lived with us, I had slept in the tiny study off the sitting room. Technically, it could be a three-bedroom flat — to which I, having dedicated my life to the Immortal Bard instead of to Mammon, was not entitled. The monstrous unfairness of it gnawed at my guts.

Watching the sun go down from the balcony, I tried to imagine what it would be like living here without Mother. I was on the opening page of a new chapter in my life. Had I been foolhardy to invite the phlegmy old woman Inna Alfandari into my life, or had I stumbled upon the only possible way to secure my home?

The more I thought about her sighs, smiles and glances, the more I wondered whether I’d been had.

Or did my dear protective mother, deliberately or unwittingly, plant the idea in Inna’s head? And what about the beautiful ward sister, whose presence had sealed the arrangement? In retrospect, there was something rather sinister about the way her elaborate white headgear perched on her dark curls without any apparent tether, and the secretive ticking of the little gold watch pinned to her bosom. Had they plotted this peculiar ménage, no doubt from the best of motives: mutual support, friendship, to keep depression at bay?

From the balcony, I watched a boy wandering down the winding path through the grove towards the road, his head bent down over a phone in his hands. As he stepped off the pavement, a speeding white van, using the street as a short cut, appeared out of nowhere.

‘Careful!’ I shouted, but I was too far away and my voice did not carry. The driver swerved just in time, the white van of destiny sped by, and the boy escaped.

‘Careful!’ Flossie screeched from inside the flat.

‘Hello, old girl. It’s just you and me, now.’

I topped up Flossie’s feeder, grateful for her chattering which cut through the stifling silence in the flat. As I filled the water bottle, I noticed that her cage needed cleaning out. It was getting disgusting. Hopefully, this was a little job that Inna, grateful to be rescued from loneliness, would be glad to take on. Pleased at my good deed, I turned on the computer in the study and tried googling various spellings of gobalki, kosabki and solatki but I drew a complete blank.

Читать дальше