He said, “I don’t think I will,” and he went into the front room and I heard his power drill go. I was so enraged that I left. I went next door to Carole’s apartment. I made myself a cup of tea. I found some pasta from the nice grocery store in her refrigerator — something my mom had bought — and I realized I had not been eating. I warmed it up and sat. I was shaking with rage. My hands were shaking violently. I ate a bite, then looked at the food, and hugged myself because I was shaking too much to enjoy the food.

The front door flew open. I heard two people, a man and a woman, going through the drawers of a credenza in Carole’s living room. I couldn’t hear what they were saying. Then one was standing in the kitchen. I knew him. It was David, a student of Rinpoche’s from New York.

I felt like a cat burglar in Carole’s house. I felt like a sneak — someone stealing. I said, “I’m never over here.”

“Yeah, right,” he said.

“This food is mine,” I said. “My mother got it for me.”

David’s wife was in the other room. She said, “I found it,” and she came into the hallway, where I could see her, but she was out of the room, behind her husband. In her hands was the iPad Rinpoche had given to Carole.

I said, “I’m pretty sure Carole gave that to my mom.”

David said, “Carole can’t read her phone.”

I said, “Carole gave it to my mom. So before you take it, can you please remove my mom’s email from it?”

David’s wife said, “You can do that.”

She brought me the iPad, but I was shaking, and I couldn’t figure out how to delete my mom’s email. They watched me struggle with it. I don’t know what came over us, but the three of us were so angry. I was as angry as I have ever been. Later, when we saw each other, we apologized with our eyes. We never talked about it.

* * *

On his first two days in Seattle, Rinpoche stayed at a boutique hotel downtown. I heard later that right after he got to town, Carole called and said he needed to come to her hospital room. “He needs to come here now. I’m dying now.”

Rinpoche and everyone piled into the van. The woman I mentioned, who massaged Carole’s feet and thought I was dumb for saying that thing about reincarnation, was driving. They drove for a while, and then Rinpoche said, “You know, we don’t have to go. She’s fine.” They turned around and went back to the hotel.

My mom and I were in our apartment. My mom was feeling left out. I was feeling astonished that Rinpoche was coming in two days, that he would be in our house.

Jim called my mom from the hotel bar.

“What?” my mom said.

He told her that he and Louise and Marc and Rinpoche were having a drink. He didn’t invite her to join them. He just let her know it was happening. My mom hung up on him.

The phone rang again.

My mom answered. She was irritated, but she was also hopeful. She hoped that Jim and Louise and Marc had called her back to invite her to join them. They didn’t. They’d just called to tease her. She hung up the phone again.

“What’s going on?” I said.

She said, “Louise said, ‘ Why’d you hang up on Rinpoche. ’ Real cute. They’re all over there laughing, having a drink with Rinpoche.”

Then I felt left out, too. It was strange to feel left out, when he would be at our house in thirty-six hours, but we felt that way. We felt like we had cleaned the place stem to stern. And now we were alone. What were we, the cleaning ladies? The help.

* * *

Rinpoche was in our living room. Even though it was clean, it sometimes had a funny smell, and so my mom and I had opened the sliding glass doors wide. A fierce ocean breeze whipped through the apartment. It whipped your hair around. After fifteen minutes, one of Rinpoche’s attendants said, “Maybe we could close the door,” and after that, we had dinner.

My mom and I didn’t know how to serve Rinpoche. It was strange to have him sitting in our apartment at a table. When I was a kid, I could do it easily, but now I was awkward. When he and his attendant had finished eating, I stumbled over to the table and blurted, “Are you done?”

I always had trouble serving. It was not because I resisted doing something for Rinpoche but because I sensed that he wanted me to be natural. I didn’t know how to do that, and so I would get tongue-tied and completely strange.

The next day we went to an outdoor mall, and Rinpoche bought an adapter so he could play songs from his iPod in the car. He handed me the adapter and said, “Can you figure this out for me?” The instructions were extremely simple. They were intuitive. But I was dumbfounded, and twenty minutes later I turned to Rinpoche and said, “I can’t understand it.”

He screwed up his face and said, “You just put one end here and one in the car.”

I shrugged.

That night at a Thai restaurant Rinpoche asked Jim and my mom why they had been fighting. They said they didn’t know. He turned to me and asked, and I tried to think of the answer.

He said, “You should write a story about it.”

* * *

He stayed four nights and we saw a lot of movies. We ate at TGI Friday’s, and shopped at Banana Republic. During the daytime people came to have short interviews with him in our place, or we went shopping. On his last day, before we came back to the apartment for a potluck dinner, he said that it was time to go and see Carole. It was just me, my mom, and Rinpoche in the car. When we got to Carole’s hospital door, I said, “We’ll wait out here,” but Rinpoche told us to come inside. Carole was happy to see him, and she didn’t mind us anymore. Whatever it was between us had passed.

Rinpoche told Carole that when she died, she would think she had to do a lot of complicated things. She would want it to be harder than it was. He said she didn’t need to do anything complicated; he said, “Just mere knowing,” and something else. It was something that simple, and he repeated both over and over, to make sure they went into her head. She was less than a week from dying, and it was the last time I would ever see her. I went to New York a few days later, and we were on the phone when we said goodbye. I told her I was sorry I wasn’t there. I said goodbye. She was distant by then. She said, “Goodbye.” We knew we were really saying goodbye. After she died, Rinpoche told Bruce to go and buy a really nice vegetarian meal and burn it. He bought a bunch of vegetables from the grocery store and lit them on fire. I made fun of him at the time, but Carole probably liked that. She loved Bruce. We were in her room for twenty minutes, but it felt like two. In the parking lot I opened Rinpoche’s car door for him. I did it because I was so grateful to know him, because it was so clear to me in that moment that everything he did was for other people. It was the natural thing to do.

Thank you Anna Stein, Jin Auh, Mitzi Angel, Emily Bell, and Susan Golomb for believing in these stories; Michiko, Ron, and Cheryl for the retreat cabin; Sam Chang and Lorin Stein for your wisdom and knowledge; “Larry,” Mom, and most of all Clancy for saving my life.

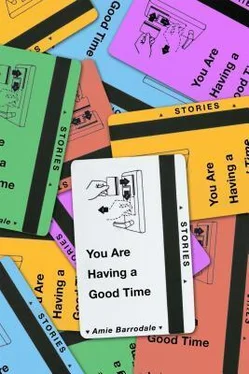

Amie Barrodale’s stories and essays have appeared in The Paris Review, Harper’s Magazine, VICE, McSweeney’s , and other publications. In 2012 she was awarded The Paris Review ’s Plimpton Prize for Fiction for her story “William Wei.” She lives in Kansas City with her husband, the writer Clancy Martin. You can sign up for email updates here.