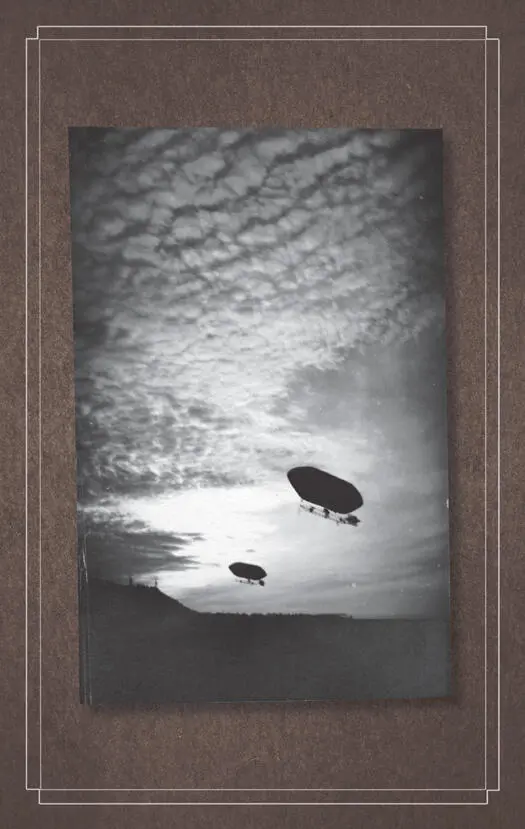

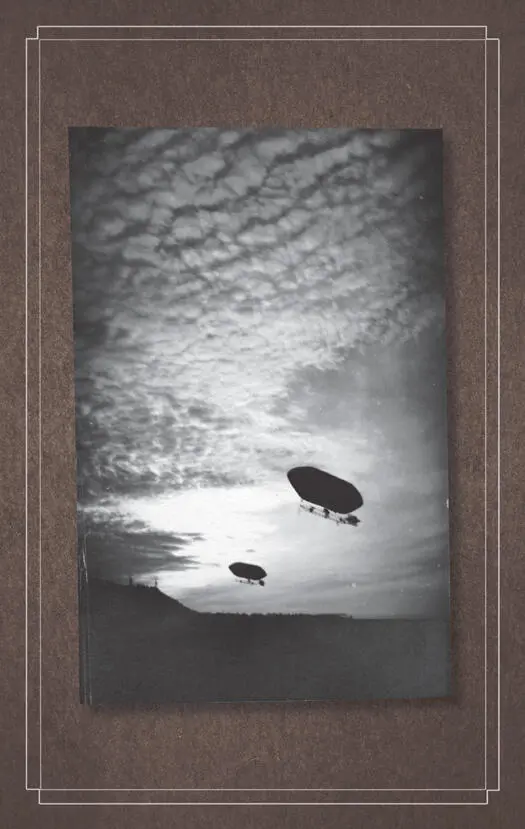

“They’re submarine hunters,” Enoch said, answering the question before anyone had asked it. Millard might’ve been the authority when it came to maps and books, but Enoch was an expert in all things military. “The best way to spot enemy subs is from the sky,” he explained.

“Then why are they flying so close to the ground?” I asked.

“And why aren’t they farther out to sea?”

“That I don’t know.”

“Do you think they could be looking for … us?” Horace ventured.

“If you mean could they be wights,” said Hugh, “don’t be daft. The wights are with the Germans. They’re on that German sub.”

“The wights are allied with whomever it suits their interests to be allied with,” Millard said. “There’s no reason to think they haven’t infiltrated organizations on both sides of the war.”

I couldn’t take my eyes off the strange contraptions in the sky. They looked unnatural, like mechanical insects bloated with tumorous eggs.

“I don’t like the way they’re flying,” Enoch said, calculating behind his sharp eyes. “They’re searching the coastline, not the sea.”

“Searching for what?” asked Bronwyn, but the answer was obvious and frightening and no one wanted to say it aloud.

They were searching for us.

We were all squeezed together in the grass, and I felt Emma’s body tense next to mine. “Run when I say run,” she hissed. “We’ll hide the boats, then ourselves.”

We waited for the balloons to zag away, then tumbled out of the grass, praying we were too far away to be spotted. As we ran I found myself wishing that the fog which had plagued us at sea would return again to hide us. It occurred to me that it had very likely saved us once already; without the fog those balloons would’ve spotted us hours ago, in our boats, when we’d had nowhere to run. And in that way, it was one last thing that the island had done to save its peculiar children.

* * *

We dragged our boats across the beach toward a sea cave, its entrance a black fissure in a hill of rocks. Bronwyn had spent her strength completely and could hardly manage to carry herself, much less the boats, so the rest of us struggled to pick up the slack, groaning and straining against hulls that kept trying to bury their noses in the wet sand. Halfway across the beach, Miss Peregrine let out a warning cry, and the two zeppelins bobbed up over the dunes and into our line of sight. We broke into an adrenaline-fueled sprint, flying those boats into the cave like they were on rails, while Miss Peregrine hopped lamely alongside us, her broken wing dragging in the sand.

When we were finally out of sight we dropped the boats and flopped onto their overturned keels, our wheezing breaths echoing in the damp and dripping dark. “Please, please let them not have seen us,” Emma prayed aloud.

“Ah, birds! Our tracks!” Millard yelped, and then he stripped off the overcoat he’d been wearing and scrambled back outside to cover the drag marks our boats had made; from the sky they’d look like arrows pointing right to our hiding place. We could only watch his footsteps trail away. If anyone but Millard had ventured out, they’d have been seen for sure.

A minute later he came back, shivering, caked in sand, a red stain outlining his chest. “They’re getting close now,” he panted. “I did the best I could.”

“You’re bleeding again!” Bronwyn fretted. Millard had been grazed by a bullet during our melee at the lighthouse the previous night, and though his recovery so far was remarkable, it was far from complete. “What have you done with your wound dressing?”

“I threw it away. It was tied in such a complicated manner that I couldn’t remove it quickly. An invisible must always be able to disrobe in an instant, or his power is useless!”

“He’s even more useless dead, you stubborn mule,” said Emma. “Now hold still and don’t bite your tongue. This is going to hurt.” She squeezed two fingers in the palm of her opposite hand, concentrated for a moment, and when she took them out again they glowed, red hot.

Millard balked. “Now then, Emma, I’d rather you didn’t—”

Emma pressed her fingers to his wounded shoulder. Millard gasped. There was the sound of singeing meat, and a curl of smoke rose up from his skin. In a moment the bleeding stopped.

“I’ll have a scar!” Millard whined.

“Yes? And who’ll see it?”

He sulked and said nothing.

The balloons’ engines grew louder, then louder still, amplified by the cave’s stone walls. I pictured them hovering above the cave, studying our footprints, preparing their assault. Emma leaned her shoulder into mine. The little ones ran to Bronwyn and buried their faces in her lap, and she hugged them. Despite our peculiar powers, we felt utterly powerless: it was all we could do to sit hunched and blinking at one another in the pale half-light, noses running from the cold, hoping our enemies would pass us by.

Finally the engines’ whine began to dwindle, and when we could hear our own voices again, Claire mumbled into Bronwyn’s lap, “Tell us a story, Wyn. I’m scared and I don’t like this at all and I think I’d like to hear a story instead.”

“Yes, would you tell one?” Olive pleaded. “A story from the Tales , please. They’re my favorite.”

The most maternal of the peculiars, Bronwyn was more like a mother to the young ones than even Miss Peregrine. It was Bronwyn who tucked them into bed at night, Bronwyn who read them stories and kissed their foreheads. Her strong arms seemed made to gather them in warm embraces, her broad shoulders to carry them. But this was no time for stories—and she said as much.

“Why, certainly it is!” Enoch said with singsongy sarcasm. “But skip the Tales for once and tell us the story of how Miss Peregrine’s wards found their way to safety without a map or any food and weren’t eaten by hollowgast along the way! I’m ever so keen to hear how that story ends.”

“If only Miss Peregrine could tell us,” Claire sniffled. She disentangled herself from Bronwyn and went to the bird, who’d been watching us from her perch on one of the boats’ overturned keels. “What are we to do, headmistress?” said Claire. “Please turn human again. Please wake up!”

Miss Peregrine cooed and stroked Claire’s hair with her wing. Then Olive joined in, her face streaking with tears: “We need you, Miss Peregrine! We’re lost and in danger and increasingly peckish and we’ve got no home anymore nor any friends but one another and we need you!”

Miss Peregrine’s black eyes shimmered. She turned away, unreachable.

Bronwyn knelt down beside the girls. “She can’t turn back right now, sweetheart. But we’ll get her fixed up, I promise.”

“But how ?” Olive demanded. Her question reflected off the stone walls, each echo asking it again.

Emma stood up. “ I’ll tell you how,” she said, and all eyes went to her. “We’ll walk .” She said it with such conviction that I got a chill. “We’ll walk and walk until we come to a town.”

“What if there’s no town for fifty kilometers?” said Enoch.

“Then we’ll walk for fifty-one kilometers. But I know we weren’t blown that far off course.”

“And if the wights should spot us from the air?” said Hugh.

“They won’t. We’ll be careful.”

“And if they’re waiting for us in the town?” said Horace.

“We’ll pretend to be normal. We’ll pass.”

“I was never much good at that,” Millard said with a laugh.

Читать дальше