Mathematics is derived through pure reason-what the philosophers call a priori reason-which means that it cannot be refuted by any empirical observations. The fundamental question in the philosophy of mathematics is, how can mathematics be true but not empirical? Is it because mathematics describes some trans-empirical reality-as mathematical realists believe-or is it because mathematics has no content at all and is a purely formal game consisting of stipulated rules and their consequences? The Argument from Mathematical Reality assumes, in its third premise, the position of mathematical realism, which isn’t a fallacy in itself; many mathematicians believe it, some of them arguing that it follows from Gödel’s incompleteness theorems (see the Comment in The Argument from Human Knowledge of Infinity, #29, above). This argument, however, goes further and tries to deduce God’s existence from the trans-empirical existence of mathematical reality.

FLAW 1: Premise 5 presumes that something outside of mathematical reality must explain the existence of mathematical reality, but this presumption is non-obvious. Lurking within Premise 5 is the hidden premise: mathematics must be explained by reference to non-mathematical truths. But this hidden premise, when exposed, appears murky. If God can be self-explanatory, why, then, can’t mathematical reality be self-explanatory-especially since the truths of mathematics are, as this argument asserts, necessarily true?

FLAW 2: Mathematical reality-if indeed it exists-is, admittedly, mysterious. Many people have trouble conceiving of where mathematical truths live, or exactly what they pertain to. But invoking God does not dispel this puzzlement; it is an instance of the Fallacy of Using One Mystery to Explain Another.

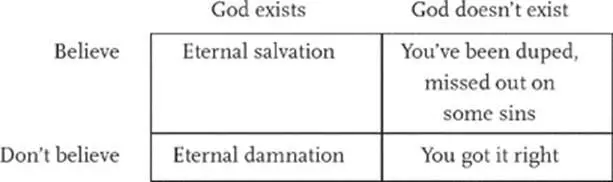

31. The Argument from Decision Theory (Pascal’s Wager)

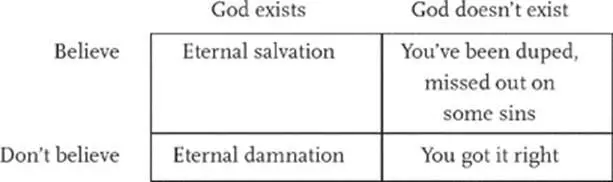

Either God exists or God doesn’t exist.

A person can either believe that God exists or believe that God doesn’t exist (from 1).

If God exists and you believe, you receive eternal salvation.

If God exists and you don’t believe, you receive eternal damnation.

If God doesn’t exist and you believe, you’ve been duped, have wasted time in religious observance, and have missed out on decadent enjoyments.

If God doesn’t exist and you don’t believe, then you have avoided a false belief.

You have much more to gain by believing in God than by not believing in him, and much more to lose by not believing in God than by believing in him (from, 3, 4, 5, and 6).

It is more rational to believe that God exists than to believe that he doesn’t exist (from 7).

This unusual argument does not justify the conclusion that “God exists.” Rather, it argues that it is rational to believe that God exists, given that we don’t know whether he exists.

FLAW 1: The “believe” option in Pascal’s Wager can be interpreted in two ways.

One is that the wagerer genuinely has to believe, deep down, that God exists; in other words, it is not enough to mouth a creed, or merely act as if God exists. According to this interpretation, God, if he exists, can peer into a person’s soul and discern the person’s actual convictions. If so, the kind of “belief” that Pascal’s Wager advises-a purely pragmatic strategy, chosen because the expected benefits exceed the expected costs-would not be enough. Indeed, it’s not even clear that this option is coherent: if one chooses to believe something because of the consequences of holding that belief, rather than being genuinely convinced of it, is it really a belief, or just an empty vow?

The other interpretation is that it is enough to act in the way that traditional believers act: say prayers, go to services, recite the appropriate creed, and go through the other motions of religion.

The problem is that Pascal’s Wager offers no guidance as to which prayers, which services, which creed to live by. Say I chose to believe in the Zoroastrian cosmic war between Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu to avoid the wrath of the former, but the real fact of the matter is that God gave the Torah to the Jews, and I am thereby inviting the wrath of Yahweh (or vice versa). Given all the things I could “believe” in, I am in constant danger of incurring the negative consequences of disbelief even though I choose the “belief” option. The fact that Blaise Pascal stated his wager as two stark choices, putting the outcomes in blatantly Christian terms-eternal salvation and eternal damnation-reveals more about his own upbringing than it does about the logic of belief. The wager simply codifies his particular “live options,” to use William James’s term for the only choices that seem possible to a given believer.

FLAW 2: Pascal’s Wager assumes a petty, egotistical, and vindictive God who punishes anyone who does not believe in him. But the great monotheistic religions all declare that “mercy” is one of God’s essential traits. A merciful God would surely have some understanding of why a person may not believe in him (if the evidence for God were obvious, the fancy reasoning of Pascal’s Wager would not be necessary), and so would extend compassion to a non-believer. (Bertrand Russell, when asked what he would have to say to God, if, despite his reasoned atheism, he were to die and face his Creator, responded, “O Lord, why did you not provide more evidence?”) The non-believer therefore should have nothing to worry about-falsifying the negative payoff in the lower-left-hand cell of the matrix.

FLAW 3: The calculations of expected value in Pascal’s Wager omit a crucial part of the mathematics: the probabilities of each of the two columns, which have to be multiplied with the payoff in each cell to determine the expected value of each cell. If the probability of God’s existence (ascertained by other means) is infinitesimal, then even if the cost of not believing in him is high, the overall expectation may not make it worthwhile to choose the “believe” row (after all, we take many other risks in life with severe possible costs but low probabilities, such as boarding an airplane). One can see how this invalidates Pascal’s Wager by considering similar wagers. Say I told you that a fire-breathing dragon has moved into the next apartment, and that unless you set out a bowl of marshmallows for him every night he will force his way into your apartment and roast you to a crisp. According to Pascal’s Wager, you should leave out the marsh-mallows. Of course you don’t, even though you are taking a terrible risk in choosing not to believe in the dragon, because you don’t assign a high enough probability to the dragon’s existence to justify even the small inconvenience.

32. The Argument from Pragmatism (William James’s Leap of Faith)

The consequences for the believer’s life of believing should be considered as part of the evidence for the truth of the belief (just as the effectiveness of a scientific theory in its practical applications is considered evidence for the truth of the theory). Call this the pragmatic evidence for the belief.

Certain beliefs effect a change for the better in the believer’s life- the necessary condition being that they are believed.

The belief in God is a belief that effects a change for the better in a person’s life.

If one tries to decide whether or not to believe in God based on the evidence available, one will never get the chance to evaluate the pragmatic evidence for the beneficial consequences of believing in God (from 2 and 3).

One ought to make “the leap of faith” (the term is James’s) and believe in God, and only then evaluate the evidence (from 1 and 4).

Читать дальше