The other man was a fisherman called Mix. He was the co-owner of a small Monterey fishing boat that went out to the islands for two or three days at a time. He’d been bringing in eleven or twelve hundred pounds of lobsters from every trip. George had seen him yesterday morning on the way to Vasco’s fish market to settle up his accounts for the past two weeks. He figured that Mix, after deducting expenses, should have around five hundred dollars as his share. Like a lot of other fishermen Mix hated to put his money in the bank right away. He liked to keep it around and look at it, though sometimes, if he was afraid he was going out to get stewed, he gave George some of his money to keep for him. The rest he went out and spent. As soon as he had two or three drinks, Mix suffered an acute attack of generosity. He bought presents for all his relatives back in Missouri, and shipped them off, live turtles, chocolates, clothes, toys, souvenirs of Channel City. He picked up all kinds of people in bars and bought them drinks and promised them free lobsters. Once he bought up all the papers a newsboy was selling and sent the boy home. The newspapers were heavy to carry, so Mix gave them away to various people. He’d brought a gift to George once, a second-hand set of the Harvard Classics. They were the only books George owned.

When Mix was stone broke he returned to his boat to sleep, and the next morning he would get the rest of his money from George and put it in the bank. George didn’t like to throw anything away, so he had a whole drawerful of receipts that Mix had returned to him when George handed back the money. Received from Mix Jorgen, to be held in trust until Monday, the sum of Two Hundred Dollars, signed, George Anderson. Mix Jorgen gave me $175.50 to keep for him, signed, George Anderson.

George put the forty-seven dollars back in his wallet. He felt suddenly very annoyed with Hazel, not because she’d asked him to do her a favor, but because she shared his own weakness. She was always getting involved with people. He didn’t like the sound of the five hundred dollar deal. He and Hazel could easily be left holding the bag.

He got the car out of the garage and drove down to the wharf to find Mix.

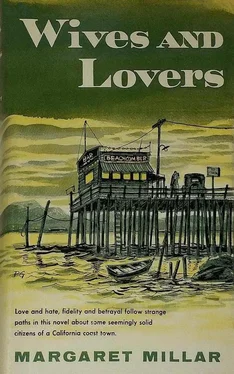

George left his car in the small parking lot beside the Beachcomber. He didn’t like to take it beyond this point, because further on some of the holes in the planking had had been covered up by thick pieces of board nailed to the planking. When one of the fish trucks hit these boards it bounced in the air, making the whole dock shudder. George preferred to walk.

The wharf was fairly quiet. The amateur fishermen were already lined up at the edge, beside the signs: “No Fishing.” “Absolutely No Fishing.” “No Fishing Beyond This Point.” As George walked on, the fish odors became stronger. A pile of empty abalone shells lay stinking in the sun. The conveyor machines, silvered with scales, smelled of dried fish blood. A young Mexican girl, all dressed up in a tight flowered crepe dress, was tying on some bait which she kept in an abalone shell. The bait was gray and black and it smelled worse than anything George had ever smelled. A small lobster boat was tied up alongside, waiting to unload. The lobsters trailed along behind the boat in crates made of laths.

He found Mix sitting against the wall of the warehouse, smoking a pipe and reading a magazine. He was a man about forty, a Middle Westerner who hadn’t seen the ocean until the war. Although he’d been a fisherman now for two years, he was still self-conscious about it. When he was not on his boat he spent hours hanging around the wharf, trying to get over the feeling that he was an impostor. He wore rubber boots, a cowboy hat, a corduroy shirt and dirty army pants.

“Improving your mind?” George said.

Mix threw down the magazine and yawned. “Habit. I started reading in the army and I can’t get over it. It’s a disease, like.”

“How’s business?”

“Hell, fishing’s no business, it’s a bum’s game. For the little guys like me, anyhow. Look.” He held out his hands. They were covered with scars and scabs and cuts. One of the cuts looked infected. “Fish poisoning. Listen, George, you take a good look at these hands and figger you’re lucky to be in a white-collar racket. Sweet Jesus, the way I work! And for what? Thirty-five cents a pound for lobster from Vasco when I could be getting forty-five at San Pedro. People like you, George, you think fishing is just sitting around sailing over the ocean blue. Sweet Jesus, if I was a sensible guy I’d go back in the army so I could do my reading by electric lights again and my pay’d come in regular instead of in fits and starts, and I wouldn’t have nothing to do with octopuses. Those things, Jesus, they get me. They get in the pots, see, and I have to gaff them. The other day one of them got me on the arm with one of his suckers. I nearly died,” he said solemnly. “I wouldn’t tell this to everybody, but when that thing got onto my arm I nearly died.”

He tapped the ashes out of his pipe for emphasis. “Eels too, I don’t like. Lobsters, now there’s something pretty about lobsters. You take a big fifteen-pound bull and watch him flopping around, he looks kinda noble. No sneaking suckers on him, by God.”

“What was the take yesterday?” George said.

“Not so good. I figure this way, somebody’s been robbing our pots, and it ain’t just starfish and eels and octopuses, it’s human. So help me Jesus, if I ever catch them I’ll use the gaff on them. Last time we only brought in eight hundred pounds.”

“Did you settle up with Vasco yesterday?”

“Sure.”

“How much?”

“Jesus, I don’t ask you how much you—”

“I need some cash until tomorrow.”

“We may be going out tomorrow.”

“Don’t kid me,” George said. “You wouldn’t go out without putting the money in the bank and by the time the bank’s open you’ll have your money back, Boy Scout’s honor.”

“I used to be a Boy Scout,” Mix said reminiscently. “Back in St. Louis. The pride of Troop Twenty-Two, and look at me now. I haven’t had a bath in a month. I wash, sure, but washing’s not like having a hot bath. Maybe some day I’ll get me a nice little apartment in town with a bathroom and a kitchen with a refrigerator, cook myself some decent meals for a change. Like this morning, you know what Pete and I had for breakfast? We figured on bacon and eggs, see, with toast. We bring out the bacon and it’s moldy. No butter, no lard. The bread don’t look so good and the eggs are getting kinda old. So Pete cooks them anyway, scrambles them in Dago red to hide the flavor. Sweet Jesus, it’s a wonder my stomach ain’t rotting away.”

“How do you know it’s not?” George said.

“I’m feeling pretty good. I feel pretty good all over except my hand is sore.” He pulled up his shirt and unfastened the money belt he wore around his middle. “How much do you want?”

“Four hundred and fifty-three dollars.”

“I’ll see if I got that much.”

He counted his money, while George watched him, amused. Mix knew down to a cent how much money he had in the belt. When he wasn’t drinking he was inclined to be careful of money, and George knew that Mix, like a lot of other fishermen around the dock who looked like bums, had a very pretty bank balance.

“Yeah,” Mix said. “Yeah, I think I got that much.”

“You know damn well you have.”

“I have to be sure, don’t I? Here. That’s four fifty-seven. Now you give me an I. O. U.”

George wrote an I. O. U. on the back of an envelope. Mix folded the envelope and put it in his money belt with the air of a man who has made a very bad bargain.

“You’ll have it back tomorrow,” George said. “On the honor of Troop Twenty-Two.”

Читать дальше