“Thank you, Gomez.”

“Or maybe polio.”

“If she phones again, tell her I’ve left.”

“Check.”

“Polio,” Ruby said, clenching her fists until the knuckles showed white. “ Polio .”

“I’d better be leaving, Ruby.”

“But you just got here.”

“I know.”

“I hardly ever see you.”

“I know that too.”

When no one was looking, he kissed her goodbye.

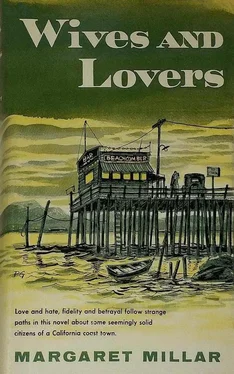

He was often late for their meetings in the back booth, and sometimes he didn’t show up at all. Ruby would sit there the entire evening, sipping coffee, which was all she could afford, and watching the front door until her eyes went out of focus and her face looked drunken in its owlish intensity.

Once in a while Mr. Gomez would pause on his way to or from the kitchen.

“Late, eh?”

“Oh, he’ll be along. He should be here any minute.”

“Maybe the wife says no.”

“She’s always saying no. That wouldn’t make any difference. He’ll be here, I’m not worried.”

“Married man.”

Mr. Gomez’s abbreviated speeches, delivered in a cracked monotone, were difficult to understand. Ruby was not certain whether he was telling her that he too was a married man and knew how it was with wives, or whether he was reproving her for having a date with a married man. It worried her. She fancied reproach in his eyes and she wanted to slap his face, the dirty little Mex, but also to explain to him that she loved Gordon, she’d given up everything just to live in the same town he did.

“It’s not fair,” she screamed mentally at Mr. Gomez, who was frying a hamburger. “It’s not fair! She’s got everything — Gordon and the house and the kids, and all I’ve got is the back booth in this lousy little joint!”

The smell of grease rose from the griddle, clung to the walls and seeped into the very pores of Ruby’s skin, blending with the cologne she had splashed on her wrists for Gordon. She felt a little nauseated and dizzy from all the coffee she had drunk, but she sat with her eyes fixed glassily on the front door. Whenever the door opened her mouth got set, ready to smile; when it closed again, and Gordon was still missing, her heart shrank and oozed its juices like the hamburger Mr. Gomez was frying on the griddle.

She never gave up hope until Gomez changed the sign on the front door from “Open” to “Closed.” Then she rose, picked up her handbag and the fox fur, and said goodnight to Gomez, very gaily, letting him know that she wasn’t at all disappointed, and that, Gordon Foster or no Gordon Foster, this was how she liked to spend her evenings, sipping coffee in Mr. Gomez’s delightful back booth.

“How the time flies,” she said brightly. “I was so interested sitting here watching the people I didn’t realize how late it was getting. You certainly have an interesting place here!”

She didn’t fool Gomez, who hated the place more than she did, and she didn’t fool herself either. As soon as she stepped outside, the cold sea wind slapped the smile off her face. I hate him, she thought, running down the street. I hate him. I’ll get back at him. I’ll get even. I’ll go and see his wife. He’ll be sorry.

But Gordon’s sorrow had already begun, and it was deeper than Ruby realized. It was the sorrow of failure. He had failed Elaine and the children, he had failed Ruby, and he had failed himself. A more self-assured man might have taken a firm stand one way or the other. The only solution Gordon could think of was to go away for a while and leave the burden of decision up to Elaine and Ruby. A vacation, he called it, when he mentioned it to Elaine. He said he thought he’d take a little trip.

“To San Francisco again? ” Elaine said with sweet irony.

“What do you mean, again? ”

“I only meant that you seem to have had such a gay time there a couple of months ago.”

“You’ve got a funny idea of a gay time,” Gordon said. “I was at lectures damn near all day, every day.” After one lecture he had picked Ruby up in a hotel lobby but he still couldn’t understand why Elaine should suspect this. “That was a business trip. A dentist has to keep up with the latest developments and equipment. This time I want a holiday. I thought of Mexico, Ensenada perhaps.”

“Mexico?”

“What’s the matter with Mexico?”

“Did I say there was anything the matter with Mexico, dear?”

“You said it as if you suddenly smelled a bad smell.”

Elaine smiled gently. “There you go imagining things again, dear. You’re getting so sensitive. I wonder if it could be glandular.”

“Listen, I know how you said ‘Mexico.’ Don’t try and kid me.”

“Really, Gordon, you’re becoming impossible. I’ve thought time and again that perhaps you should go and see a doctor. Glandular disturbances are common at your age.”

“Jesus Christ,” Gordon said, sweating.

“All this fuss simply because I said ‘Mexico’ in a perfectly ordinary tone of voice. I’m sure I’ve got nothing against Mexico. Of course I’ve heard it’s terribly dirty. You can’t drink the water at all without boiling it, and you have to be awfully careful about the food, cholera and things like that.”

Elaine could, with a few well-chosen words, reduce anything to its lowest common multiple. Having deflated Gordon and crushed Mexico, she went to work with undiminished fervor on vacations in general and Gordon’s in particular. It was a funny thing, Elaine said, that men took vacations every now and then while women went right on year after year without any kind of rest or holiday at all. Anyway, did Gordon really think it was wise to leave right now?

“After all, dear, you’ve got your family to think about. It isn’t as if you were in some business that could carry on without you. I mean, every day that you’re not at the office and don’t keep your appointments, you’re losing money. You have your overhead, and Hazel’s salary, and you know how many new dentists, all of them veterans too, are opening up offices here. After all, you’re in a competitive profession. If you’re going to be away from the office half the time your patients are going to feel that they can’t depend on you.”

In one short speech she had managed to convey to Gordon that he was a shirker who hadn’t helped win the war, as well as lazy, impractical, thoughtless, incompetent and irresponsible.

Elaine considered herself a true gentlewoman. She never raised her voice or swore, and even when driven into a corner by fate she used only legitimate womanly weapons like her children, her bed and soft words strung on steel. She had betrayed Gordon on the day she married him by telling her mother that she knew Gordon had a weak character and that she would have to be strong for both of them. Elaine often recalled this speech, which she termed “realistic,” and which she considered remarkably shrewd for a girl so “young” — she was twenty-seven on the day she was married. Not six months later, she told Gordon of her speech to her mother. Gordon was shocked, not by her malice, which she had already revealed in many small ways, but by the fact that she despised him. She made it clear that it was only her own iron will and determination which kept Gordon on the straight and narrow and confined him to his office twelve hours a day. Gordon was thirty then, and working very hard to build up a practice so that he could buy Elaine a new house. He was quite surprised to find out that he was a weak character, and inexperienced enough to take the criticism seriously. In the end, after Elaine had given him a gentle heart-to-heart talk, Gordon was convinced that he was indeed weak and that it was Elaine’s personal power that turned the drill and kept him confined in the magnetic circle of office-and-home.

Читать дальше