Théodora Armstrong

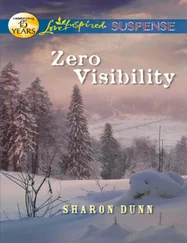

CLEAR SKIES, NO WIND, 100% VISIBILITY

STORIES

For my parents

and for J, with love.

I WRAP MYSELF IN our scratchy curtains and watch Mom from our front window. The glass is freezing. I can feel the cold without touching anything. My brother, Matt, is sleeping on the couch behind me. He’s snoring and his shoes are still on. His jacket is on the floor beside him. He looks ready for a quick escape, but he’s been here for a while now, almost a year. He has a toothbrush Mom bought for him. He’s hung a movie poster in his bedroom, Scarface . I guess that’s a good sign.

It’s too early for visitors, but Mom is in her fuzzy blue robe and thick woolen socks, talking to our neighbour on the porch. I don’t know his name, but sometimes I see him early in the morning walking to his car in a suit and tie.

It snowed last night — the first snow — enough to get to my ankles. Mom’s breath is thin like a beautiful bubblegum balloon, reaching out and almost touching the neighbour before vanishing.

Mom comes back into the house, all the cold running in with her. She can’t see me behind the curtains. She stands watching Matt for a while. I wish I could snore like him, like a bear asleep in a cave. I poke my head around the curtains, moving them carefully so I don’t wake up Matt. “Get a move on,” Mom whispers. “I’m giving you a ride to school this morning.”

I SIT IN THE car while Mom warms it up. I’m in a white envelope being mailed to China or Peru. She knocks ice and snow off the windshield with her mitts. Usually I walk to school — it’s not far, four blocks on the other side of the mall, but the mall is a long block and counts for at least two. I want to ask why I’m being driven to school, but weird things early in the morning always mean bad news. Mom keeps forgetting things, running back and forth from the car to the house. She spills her coffee getting into the front seat and swears. For a minute I think she’s forgotten I’m here.

There are a lot of people on our street this morning. Most of the time our streets are empty. In the morning or at dinnertime cars are in and out of driveways, but there are never people on the sidewalks. Sometimes I feel I’m the only one who walks on our street. But this morning people are out, walking in groups of four or five, holding steaming cups of coffee, calling greetings to each other. They look like carollers, but I’ve only seen carollers in my Christmas books. At the end of the road, police cars are parked around the brown house with the windmill on top. Mom slows down as we drive by, and for a second I think we might stop to join everyone, but instead we turn the corner and head toward the school. “There was a girl that went missing last night,” Mom says. “She never came home from the mall. Did you hear anything?” I shake my head no.

Along the river, the tree branches are heavy with snow. There are police cars here too. I turn up the heat, hot air blowing in my face. Mom turns the dial back down.

NOT MANY KIDS AT school know about the girl, so at recess I tell everyone. I say what she looks like even though I’ve never seen her. She has long blond hair in braids. Her eyes are green. She was wearing a jean skirt and winter boots. Everyone crowds around me in a tight circle. They go off to make other circles. Soon everyone is in circles.

After recess, Ms. Peterson makes a special announcement to the class. She uses the word abduction . She tells us what to do if we meet a stranger. We don’t take candy. We don’t tell anyone our names. We scream. People turn to stare at me, their eyes huge like moons, and it’s official now: I told everyone first.

SAM’S MOM IS GOING to take me home before she takes Sam to his swim lesson. Sam’s in my class, but we never play together because he plays kickball every day, even in the snow.

When they drop me off they walk me right to my front door. Matt cleaned off the stairs this morning and all my footprints are gone. I feel grown-up taking out my key chain with the blue dolphin and unlocking the door. Sam doesn’t have a key chain or a key, and he was looking at mine while we waited in the schoolyard. He was pretending to make the dolphin dive in the snow, but I was afraid he’d lose my keys and I wouldn’t be able to go home, so I took them back.

We talked about the girl. She’s not really a girl. I’m a girl; she’s a teenager. But everyone calls her a girl — that poor girl, that innocent girl. Mom told me a bit and Sam told me the rest, but no one really knows anything about her. Someone took her while she waited for the bus in front of the mall. She went to Ferndale High. I don’t think I knew her, but one day I might have walked beside her without realizing. She screamed a lot. Lots of people heard her, but everyone kept drinking their tea and watching their television shows. Sam says he heard her, but I think he’s lying. Mom says she thought it was teens down by the river goofing off.

Sam and I stand by the front door staring at each other while Sam’s mom looks around my house. She wants to know where my brother is and I tell her he gets home from the glass factory at four. When I picture the glass factory I see nothing but stacks of window panes. Once Matt picked up a sheet of glass with unfinished edges and slit his palms open. Mom says he’s lucky to have his fingers. You’re supposed to wear heavy gloves at all times. He was at home for a month with fat white bandages around his hands. He liked to pretend they were boxing gloves. He still has the scars.

When Sam’s mom leaves she tells me — same as Mom did — not to open the door for anyone. I hear them wait until I turn the lock before they make their way down the steps. I run to the front window to watch their car pull away from the curb. Sam watches me from his window. I make the blue dolphin bob up and down as if the windowsill is an ocean.

I TURN THE HEAT up as high as the dial will go. There’s a heat vent beside the sliding doors in the kitchen that look out on our backyard. I sit there with a box of Froot Loops and let the hot air puff out my T-shirt. The house is quiet like a forest. I feel like animals are hiding everywhere, under the sofa, in the cupboards, behind the doors. Matt isn’t home yet and because of the snow it’ll take him longer than normal.

If Matt gets home before me, he’s usually on the deck with his .22 rifle. I like to sit on the vent and watch him. Matt just turned twenty. We had meatloaf on his birthday and Matt ate seconds. Last year, we didn’t get to celebrate his birthday because he was living in Port Alberni with Uncle Pat and working at the lumber mill. Before that he was with Grandma Alice in Vancouver and before that I can’t remember. The last time he left, he didn’t say goodbye. Mom forgot to tell me he was gone because he comes and goes as often as cats want out. One day I asked her where he was and she looked dazed. She said: Oh, honey . She said people need space to breathe and I thought that was pretty obvious. Everyone needs space to breathe or else they’d be dead.

But Matt always comes back — one day he opens the front door and he’s here. There are twelve years between us. Mom says that makes him responsible for me.

Matt likes to shoot soup cans from the deck. He stacks the empty cans on tree stumps at the back of the yard. They’re old and rusted together, the labels peeled and curled — beef barley, cream of mushroom, chicken noodle. I make the soup when Mom’s late from work. Behind the stumps are trees and behind the trees is the river. After you cross the river you get to the mall.

It takes Matt a long time to shoot. He aims carefully, adjusting his arm a lot. The bullet flies when I least expect it, but it never makes me jump or even blink. He almost never hits a can.

Читать дальше