All this meant that people no longer came to visit their relatives in the cemetery, Fulvio told me. I asked why, and he said I had to be kidding him. Don’t they know in America what’s going on down here? It’s the dead, they come out at night in the form of dogs and visit their relatives. So why would anyone come in here anymore, when your relatives come right to your door? All those people died in the epidemic, Adriano said, and the dogs started showing up almost a year to the day after their burials. It’s not just people who died in the epidemic, said Fulvio, because there was never any illness in Coronel Pringles and there are night dogs there now too. The teenage lackey nodded as his two masters spoke; he was, I guessed, Fulvio’s son, he shared his broad brow and deep, impenetrably black nostrils. I had not heard the news of a recent epidemic afflicting Buenos Aires, but then again, I never paid attention to world affairs. So the epidemic I was prepared to accept, but Fulvio’s theory of the night dogs I regarded as suspect, and I told him so. That’s what everyone who isn’t from around here says, he answered, you just wait till it happens in your city. My friend in Coronel Pringles thought I was full of shit too, and now he’s pissing himself because the dogs have showed up there and he thinks he’s going to go out of business. He runs a funeral parlor, replied Adriano, no way he ever goes out of business.

I took another step toward the cemetery lawn. If you don’t believe me, said Fulvio, you can go check for yourself. I assured him that I did believe him, but he was already furious. You don’t even know anything about this city, you’ve been here one night and you already think you’re an expert, he shouted. His voice racketed through the marble entrance plaza, through the gates. My initial instinct, to flee, faded. I saw no reason why I should allow this flower salesman to bully me. As an expert on prison architecture, I was, by extension, an expert on the human body (a primordial prison) and the soul (the prisoner or alleged prisoner). I told him to calm down, I hadn’t meant anything by it. It was a strange story, he had to admit. It’s only strange, said Fulvio, if you want it to be strange. People think that because we landed on the moon, stuff like this doesn’t happen anymore. Well, first of all, it was you people who landed on the moon, we never did, and second of all, that’s a logical fallacy. The lackey came up behind Fulvio, eyes wide in fear. Adriano told his brother to calm down. I offered my hand to Fulvio. This gesture surprised me. I did not under ordinary circumstances engage in social theatrics. I’m usually a peaceable man, he said as he shook my hand, but on this issue, I just can’t stay quiet. His palm dry and soft. Crossed by a scar. His skin left a golden smear of pollen on mine.

AHEAD OF ME, AFLOAT in the dimness, a stripe of raw-looking flesh. I did not mention the coincidence to the cabbie as he drove along Directorio, and I held my tongue as he reached Avenida San Juan. I was waiting for him to speak. He did not. His silence was absolute. This exerted pressure on me, on my so-called soul, as it would have on the “soul” of any fellow primate. I asked about the dogs, since I could not ask about his carbuncles, i.e., his identity. He remained sunk in his marmoreal silence.

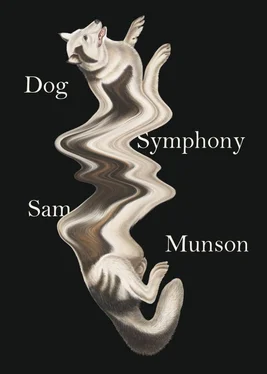

The buildings, mackerel-gray, salmon-rose, or white, empty white, wavered, ready to take wing. A common effect of insomnia. At doorsteps and lobby entrances, human figures knelt to place meat and pour water into steel bowls; many took the meat from silver freezer bags, while others dumped it out of plastic grocery bags; the water came from hoses, buckets, and pitchers. At a stoplight, I saw one pitcher shaped like a rooster, water leaping from its beak. Neighbors greeted each other as they might during any outdoor chore. The houses without these offerings looked desolate, a desolation increased by a lonely, muted noise filling the cab. A distant murmur, punctuated by occasional bell-like tones. I thought it was an eccentric engine sound, until the driver took his earphones out as we arrived at the social sciences building. It was music. Drums and cymbals overlaid, with shrill flute notes interrupting: the song I had first heard in the airport, the song I’d heard again pouring from the clerk’s radio in the all-night shop on the corner of Emilio Mitre and Hualfin. My driver said it was called “Dog Symphony.” He didn’t know who wrote it, he didn’t know how long it had been popular. It was always popular, he said, I think.

I was due to meet Ana in a lecture hall on the first floor of the social sciences building on Alvear. From the outside it resembled a small suburban hospital. I knew the layout of the building as well as I knew the layout of the city streets, thanks to the ample conference brochure I’d received. The first floor contained the main lecture rooms; above it, on the second floor, what an Argentine would call the first floor, was the sociology department, above that archaeology, then anthropology, economics, media studies, gender studies, and indigenous studies. History, where Ana served, was found on the eighth floor. Yet of the students themselves I knew nothing. Maps can tell you nothing about student moronism, sadly, other than where you are likely to find it. But as I passed among these hurrying adolescents, I understood how apposite Ana’s remark had been: they were no more than burgherly poltergeists. Heads, lips, scarves, eyes. All these filled the air. Glances slid fluidly and blankly over my face, over the walls and the high, dirty ceiling. They moved with studied, I thought, freneticism, evincing all the might of the young, exuding the pitiable, vermiform energy that characterizes youth, especially student youth. And they like my own students were divided, they too comprised two armies. That I noted at once. Half the students, male and female alike, wore nylon chokers with dog ID tags attached to them. The tags chimed softly as they walked. Tag wearers spoke only to tag wearers; those with naked necks spoke only to those with naked necks. The music the cabdriver had listened to with devotion trilled and buzzed. From headphones buried in student ears the noise leaked out. It poured, as well, from the open door of a men’s restroom, along with an ammoniac stink. The janitor plunging his mop into the mottled zinc bucket had a small radio affixed to his cart.

In a niche near the door of the lecture room we were scheduled to present in, a marble man in a marble suit with a marble mustache stood watch. Next to him, a fat, bald woman was waiting with two friends, both dark haired. One tall, her face oblong, and one short, her face also oblong. They weren’t wearing tags. All three muttered to each other in quiet, rapid bursts, as if exchanging strings of obscenities. They paid no attention to me. The fat woman was saying that she did not understand why the department got all the funds for renovation, while in indigenous studies they had to starve. Her shorter interlocutor said: You knew it was going to go this way, you had to — that’s why things have come to a head. Her taller interlocutor said that she didn’t even consider the department real scholars. You lack a feeling for class consciousness, said the fat woman. I peered through the doorway into the lecture hall. I saw slumberous students, dust motes wheeling in a shaft of southern sunlight, and the low dais from which I would be delivering my talk. The table on the dais, around which the tiered seating rose up like ship walls, held two places, two notebooks, two pens, two blue folders. But no Ana.

I contemplated rushing to her office and rushing back. But I knew that if I left the exiguous audience would leave as well. There were no more than a dozen attendees. The fat, bald woman. The two women who had come in with her (they sat near the front, already taking notes; their pens made coleopteran scratching sounds). A boy with a blank, white face and well-greased hair. He belonged to the faction that wore dog ID tags. He was handsome; he looked, in fact, like a beardless Che Guevara. The students sat, silent or (in the case of the fat woman and her friends) whispering to each other. They avoided looking at me and I avoided looking at them. Instead, they looked through the tall windows that let out onto the quadrangle, and I looked as well. A woman passed by, wearing the sky-blue livery of the officers I’d seen at the airport. Then two men. Then another man, alone. The students seemed uneasy. One of them, I did not see who, whispered: I don’t understand, I don’t understand. His voice threatened to swell into a complaint, a howl, so I simply started talking, introducing myself and making excuses for Ana, and then launching into my presentation.

Читать дальше