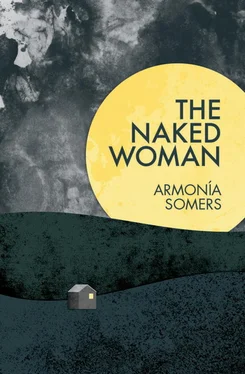

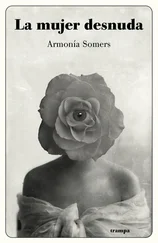

Armonía Somers - The Naked Woman

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Armonía Somers - The Naked Woman» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: The Feminist Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Naked Woman

- Автор:

- Издательство:The Feminist Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-93-693-244-3

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Naked Woman: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Naked Woman»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Naked Woman — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Naked Woman», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Elena Chavez Goycochea

“Who would you like to talk to, the teacher or the writer?” That was the sharply worded question Armonía Somers often posed to journalists seeking an interview with her. If they wished to meet the teacher, she would ask to hold the conversation at the Library and Pedagogical Museum in Montevideo, where she worked for more than ten years; whereas the writer would request they meet in her home. [1] Reyes Moreira 1959.

In this way, she managed to split her life in two: Armonía Liropeya Etchepare Locino, the teacher, was born in 1914 in Pando, a small city in Uruguay, to an anarchist father and a Catholic mother; the writer came into being in 1950, when La mujer desnuda ( The Naked Woman ) was published in a local literary magazine under her pen name Armonía Somers. [2] Somers 1950. The magazine is Clima: Cuadernos de arte .

Since then, the author has become a legend among Latin American readers and a challenge for critics and translators, so much so that it took more than six decades for us to be able to hold in our hands the English edition of her groundbreaking first novel.

The transition from Etchepare to Somers was a gradual one, as she managed to compartmentalize both identities, keeping them professionally separate for about twenty years after the release of La mujer desnuda . Living as Armonía Etchepare, she was a passionate schoolteacher and renowned researcher who published numerous essays on youth and education. Her advocacy for equal access to open-minded education led her to a successful career in public service, first as assistant director of the Library and Pedagogical Museum of Uruguay and, later on, as chief director of the Center of Educational Documentation and Dissemination in Uruguay. However, after publishing several other works of fiction—such as the collection of short stories El derrumbamiento in 1953 and the novels De miedo en miedo in 1965 (written in Paris while researching for UNESCO) and Un retrato para Dickens in 1969—Somers abandoned what she called her “civic life.” By 1971 she had quit her job as an educator and devoted her life to her literary career. The shift toward a new identity was not only a strategic decision—Uruguay was in the process of transforming into a civic-military dictatorship in the early 1970s—but also an artistic statement that has endured until the present day. [3] I draw on the two publications that give accounts of Somers’s trajectory as a writer: Cosse 1990 and Dalmagro 2009.

It was common for nineteenth-century writers to write pseudonymously. Generally, authors readily adopted pen names to distinguish the person from the persona, the private from the public. Women writers employed pen names to the same end, yet also used them as part of what critic Elaine Showalter has called the “assimilation process.” [4] Showalter 1985.

Victorian women writers, for example, adopted male pseudonyms to assimilate into literate society where writing practices were associated with masculine values. Such was the case with George Eliot—given name Mary Anne Evans—or the Brontë sisters, whose first stories were published under male names.

Armonía Somers’s name change differs from these examples in that she was driven by a distinct purpose: the desire to construct a new woman writer, one capable of writing outside of social conventions and apart from any contemporary literary trend. Moreover, her gradual transition from Etchepare to Somers was motivated by her eagerness for freedom: “I realized how much more leeway fiction offered me in comparison to nonfiction, for I could play with that reality in a game that freed me.” [5] Picon Garfield 1987, 37.

Taking advantage of that leeway, her writing would ensure that women’s bodies and sexuality were no longer marginalized in social debates taking place in the public sphere.

Furthermore, Somers’s identity performance allowed her to approach language in new ways: for example, as a mechanism capable of conveying meaning through silence. As her narrator observes in The Naked Woman , “She learned to revel in the silences and to disappear like a ghost” (114). Paradoxically, the literary gesture of silence and identity performance entailed a protest, upon which ethics and writing were clearly intertwined in a nontraditional way.

As I have said, maybe this decision was not only because I liked Armonía Somers as a name… or because it actually was a shield against any judgmental comment that people might make about me as a person who was working as a schoolteacher, and writing such things afterward. It was not only that, but maybe it was a protest. [6] Risso 1990, 254 (translation my own). “Yo he dicho que a lo mejor no era solamente que a mi [ sic ] me gustara el nombre de Armonía Somers por que [ sic ] lo prefiriera, pues me dejaba un poco a cubierto del juicio que pudieran tener sobre mí como una persona que ejercía una carrera normativa, y escribiendo tales cosas después. No solamente por eso, si no [ sic ] que a lo mejor era una protesta…”

Although Somers never considered herself a “social novelist,” nor followed the aesthetic of literary realism, she was clearly a social thinker following her own path. Her ethics and aesthetics put the body—mainly women’s bodies—at the center of artistic and social debate, making visible what was historically overlooked. As French feminist Hélène Cixous pointed out in The Newly Born Woman , women writing about their bodies reveal in them a form of communication that differs significantly from ordinary language, which has historically been organized by masculine desire. This is clear in The Naked Woman when Rebeca Linke removes her clothes at the beginning of the novel, her naked body becoming a “cause” that seeks to defy patriarchal rules in society. “The cause? Yes, the cause,” confirms the narrator toward the end of the novel. Departing from the myth of Adam and Eve, the Naked Woman demystifies and subverts precepts governing the body, often resisting and reshaping forms of socialization around her.

In order to further spark “protest” through her fiction, Somers adopted literary styles and techniques that drew upon everything from surrealism and stream of consciousness narration to nineteenth-century European and Latin American Romanticism. She was also indebted to the literary tradition of the fantastic, in which the unreal, the real, and the possible coexist simultaneously: moments such as Linke decapitating herself or communing with the horse. For taking such a radical, defiant stance in terms of her stylistic and thematic choices, Somers was often called a “parricide” by critics, implying that by not following in her literary forefathers’ footsteps, she had in fact “killed” them—most being regionalist, naturalist, and realist male authors concerned with depicting sociopolitical reality through facts and detailed descriptions. While most traditional novelists followed the popular European school of naturalism—which used a third-person omniscient narrator to view the novel’s action from a distance—Somers’s narration instead moves in and out of her characters’ minds. At times she adopts the Naked Woman’s oneiric fantastic perspective or the preacher’s religious anguish, and at other times she uses the voice of the narrator to observe her characters with a wry sense of irony.

Somers invites us to experience reading as a game of possibilities, playing equally with the ambiguities of silence and sound, nudity and covering, and darkness and light, preventing us from becoming complacent in the rigid structure of accepted thought. Even Rebeca Linke’s multiple deaths are not simply the end of her life, as it is commonly understood in modern history, but the beginning of a new cycle. Somers’s writing suggests, then, that the linear trajectory of women’s lives has been a social myth that ought be transformed.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Naked Woman»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Naked Woman» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Naked Woman» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.