Did a person have a right to attachments under those circumstances? War-time friendship is piercing, just as war-time love is piercing: everything is as if for the last time. This is grounds for experiencing those attachments with the utmost keenness or, conversely, for renouncing them completely. What did the general choose at the time?

He chose reminiscences. In the event of the possible absence of a future, he extended his life by experiencing his past multiple times. The general sensed, almost physically, a living room with silk wallpaper, along which his shoulder glided when he was escaping the attention of guests after—obviously at his parents’ order—one of the servants had abruptly brought him here, into a kingdom of dozens of candles, clinking dishes, cigars, and huge ceiling-high windows that were recklessly thrown open in Petersburg’s Christmas twilight. The general firmly remembered that the windows were open, against the usual winter rules; he remembered because for a long time he continued considering Christmas the day when warmth set in. Remembering that, he knew he had been mistaken.

But the general had a certain something else to recall on his evenings before battle: his first visit to the Yalta beach. It is described in detail in the portion of the general’s memoirs published by Dupont, which permits stopping at key moments of that event while omitting a series of details. What affected the child more than anything else was the sea’s calm force and the power of a frothy, ragged wave that knocked him from his feet and carried him away during his first approach to the water. Unlike the other members of his household, he was not afraid. As he leapt on shore, he was purposely falling on the very brim of the surf, allowing the elements to roll his small, rosy body. Overcome by all the sensations, he jumped, shouted, and even urinated slightly, observing as a trickle that nobody noticed disappeared into a descending wave, vintage 1887.

The beach occupied a special place in the child’s life from that point on. Even in the 1890s, when circumstances did not always permit him to appear there naked, the joy of the future military commander’s encounter with the beach was not diminished. As before, he encountered the waves with a victorious cry, though he still did not allow those excited behaviors that marked his first meeting with the watery element.

Despite the ceremoniousness of the nineteenth century, this period had its own obvious distractions. In those years, when dresses had just barely risen above the ankle and no one was even dreaming of uncovered knees, fully undressing was, in a certain sense, simpler than now. Nude swimming among peasant men and women and, what is more, the landed gentry, was not something out of the ordinary in the Russian village and was by no means seen as an orgy. This simplicity of values concerned the beach at times, too. Prince Peter Ouroussoff’s Reminiscences of a Vanished Age notes that visitors to private beaches in the early twentieth century could even bathe naked.

Even so, the beach had arrived as a Western European phenomenon, bringing its own series of rules. One needed to dress for the beach, albeit in a particular way: not in usual undergarments but in a special style of tricot that was striped and clung to the figure in an interesting way. The shortcoming of a beach outfit, however, was the same shortcoming of other clothes from that time: it left hardly any parts of the bather’s body uncovered.

When fighting in continental Europe, the general invariably recalled the beach: the damp salinity of the wind, the barely discernible smell of cornel cherry bushes, and the rhythmic swaying of seaweed on oceanside rocks. With the ebb of a wave, the seaweed obediently replicated the stones’ forms, just as a diver’s hair settles on his head like a bathing cap that gleams with the water that flows from it. The general remembered the smell of blistering hot pebbles after the first drops of rain fell on them and heard the special beach sounds: muted and somehow distant, consisting of children’s shouts, kicks at a ball, and the rustling roll of waves on the shore.

For the general, the beach was a place for life’s triumph, perhaps in the same sense that the battlefield is a place for death’s triumph. It is not out of the question that his many years sitting on the jetty were brought on by the possibility of surveying (albeit from afar) the beach, legs crossed, in his trusty folding chair under a quivering cream-colored umbrella. He only looked at the beach from time to time, his body half-turned, but that gave him indescribable pleasure. Only two circumstances clouded the general’s joy.

The first of those was the presentiment of winter, when a beach drifted with snow transformed into the embodiment of orphandom, becoming something contrary to its initial intended designation. The second circumstance was that everyone he had ever happened to be with at the beach was long dead. Hypnotized by the beach’s life-affirming aura at the time, the general had not allowed even the possibility that death would come for those alongside whom he was sitting on a chaise longue, opening a soft drink, or moving chess pieces. To the general’s great disappointment, none of them remained among the living. No, they had not died at the beach (and that partially excused them) but still they had died. The general shook his head, distressed at the thought. Now, after the passage of time, it can be established that he has died, too.

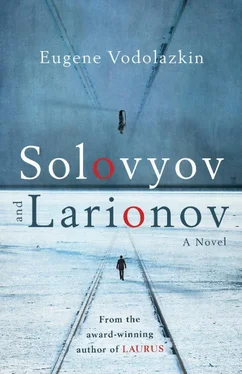

Historian Solovyov appeared on the Yalta beach twenty years after General Larionov’s death. Solovyov’s first encounter with the sea did not proceed at all like the future military commander’s. Solovyov came to the sea as an adult, so carefree rolling around in the waves seemed indecorous to him. The researcher had also had the chance to familiarize himself with the corresponding part of the general’s memoirs before making his appearance at the beach and the very fact of that reading would not have permitted him to do—as if for the first time—everything the young Larionov had permitted himself. Undoubtedly, contrivance and even a certain derivativeness would have shone through any attempt of the sort. As Prof. Nikolsky’s student, Solovyov essentially thought that no events whatsoever repeat themselves because the totality of conditions that led to them in the first instance never repeats. It should come as no surprise that attempts to mechanically copy some past action or other usually evoked protestation in the researcher and struck him as cheap simulations.

Solovyov’s behavior differed strikingly from Larionov’s. The young historian took a towel from his rucksack and spread it on the warm evening pebbles. After taking off his shorts and T-shirt, he laid them neatly on the towel, stood up straight, and was immediately acutely aware of his own undressedness. Each hair on Solovyov’s skin—which was untanned and visible to all—sensed a caressing Yalta breeze. Solovyov knew this was exactly how people went around on the beach but he did not know what to do with himself. He pressed his arms instinctively to his torso, his shoulders slouched, and his feet sunk conspicuously into the pebbles. Solovyov had not just come to visit the sea for the first time: he had never in his life been on any sort of beach, either.

Making a concerted effort, he headed stiffly toward the water. The pebbles, which the waves had polished to shining, became surprisingly hard and sharp under the soles of Solovyov’s bare feet. He tottered, shifting from one half-bent foot to another as he balanced his arms in the air and desperately bit his lower lip. This helped him reach the spot where the waves were already rolling in. This sparkling area only seldom remained dry, during the brief instant between ebbing and incoming waves. Even in that instant, though, he could see that it was covered with small, fine stones that were turning to sand, which the sea carried away. Standing here was thoroughly enjoyable.

Читать дальше