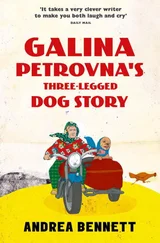

Albina strode with splaying steps between the empty potato rows and the bare plum trees, anorak soaked through with dew and the effort of digging. It was still only eleven a.m. Despite the dark mornings and the chill in the air, a visit to the dacha always meant an early start. It didn’t feel right if he arrived when the birds had already finished their morning chorus and disappeared into the blackthorn bushes.

‘Do they have dachas in Armenia, Mister Papasyan?’ Albina asked as she dropped down next to him on the bench, picking soft mud clumps from her sleeve as she did so.

‘Call me Gor, child; I think we’re past formalities now. And yes, I expect they have dachas .’

‘What do you mean, you expect so? Don’t you know? You are Armenian, aren’t you, Gor?’ she raised an eyebrow, tone accusatory, although she was smiling.

‘I don’t know that either.’ Gor hummed to himself as he brought out two chipped cups, a box of sugar cubes, a bag full of pryaniki, and an old, mottled spoon.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well… my father was from Armenia. But he met my mother in Rostov… way back, in the 1920s. They married, and together, they moved to Siberia, where I was born, in the 1930s. After the Great Patriotic War, I moved back to Rostov, and that is where I made my home. In total, I have visited Armenia only once, to meet distant relatives, show off my family and discover the mountains. So you tell me: what am I? Am I Armenian? Siberian? Rostovian?’

Albina was eyeing the pryaniki , and shrugged. ‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘Can I have…?’

Gor passed the bag of biscuits to her.

‘You see, I used to be a Soviet citizen, and that suited me quite well. We were all Soviet citizens. But they no longer exist. Now it pays to be Russian.’

‘Hmmm,’ she said, chewing heartily and not listening. ‘So, you don’t know anything about Armenia?’

‘Well, I know things, I can tell you things, but it’s mostly from books and papers, or the TV news.’

‘It’s very small, isn’t it?’

‘Compared to Russia, yes.’

‘Tell me about your father.’

‘Well, my father died when I was quite young—’

‘Young like me?’ she asked.

‘Not quite that young. When you get to my age, anything below fifty is young. He died when I was in my early twenties. So—’

‘What did he die of?’

‘His heart.’

‘A broken heart?’ Albina’s eyes widened.

‘A heart attack. People don’t really die of broken hearts.’

‘No?’ She looked disappointed.

‘No. They carry on. It’s miserable, but not fatal.’

Albina took another biscuit. Gor fell quiet, staring out from the bent veranda into the misty gardens. The water in the samovar began to simmer with a homely, bubbling sound, and he opened up the tap on the front to fill the battered metal teapot. After giving it a good stir, he placed it back on the flat top of the samovar to keep warm.

‘There,’ he said, ‘now we have tea for the whole morning. We just pour a little into each cup, and top it up with the hot water as we go. There’s the sugar. Just help yourself.’

‘I don’t like tea,’ said Albina.

‘Ah,’ said Gor.

‘But it doesn’t matter.’

‘I see,’ said Gor. ‘You can have hot water then, to keep you warm. And perhaps you’d like a boiled egg? Better for your teeth than pryaniki ?’

The girl thought for a moment. ‘Maybe,’ she said at last, wiping biscuit crumbs from her lips. He drew out his ancient canvas knapsack from under the table and unwrapped the eggs.

‘I have salt and pepper. I can’t abide an egg without salt and pepper.’ He smiled at the girl, showing his long, gnarled teeth.

Albina nodded in a non-committal way, and picked mud from her wild, shaggy hair. Gor wondered if he should have told her to tie it back. He had no idea how to handle pom-poms, and did not possess a hairbrush.

‘Have you seen the disappearing egg trick?’ he asked.

‘No!’ Albina turned to him eagerly. ‘Can you really make them disappear? Is it real magic?’

‘Well,’ began Gor, ‘it’s a trick, that’s the whole point. Making things really disappear would be—’ He stopped, aware that her interest was seeping away. ‘But, actually, yes, of course: I’m a magician. I can make all sorts of things disappear.’

She smiled and clapped her hands. He took up an egg and a chequered tea-towel, flourished the egg, flourished the tea-towel, put them together and – pop! – shook out the tea-towel with the egg nowhere to be seen.

‘Ahh!’ squealed Albina, bouncing up and down. He smiled, leant forward with a demonic look, shook his cupped hand by her ear, uttered the magic words ‘hey presto!’ and – pop! – the egg reappeared.

‘Ha ha! That’s excellent! Can you do it with two eggs?’

He hesitated. ‘Er, no. That would be impossible.’

‘No, try! I want you to!’

She forced another egg into his hand, the shell cracking as she did so.

‘No, I’m afraid two eggs won’t work. Stop it! But this egg is now magic.’ He gave her a serious, dark-eyed look, and she stopped still, her face half scorn, half wonder. ‘Are you brave enough to eat it, or shall I?’

She eyed the egg, held out towards her in Gor’s spidery hand. ‘If I eat it, will I become a good person?’ she asked, her voice serious.

‘Albina, you don’t need a magic egg to be a good person. Look at you: you yourself – you are goodness. Just listen to your conscience, and don’t drown it out with your own noise.’ He shrugged. ‘It’s the same for everyone.’

She thought for a moment. ‘OK, in that case, you have it. I think you need it more.’

Gor snorted and cracked the egg on the side of the table.

‘Why do you like magic so much?’

He shook pepper onto the dome of the egg and took a bite. ‘Oh, that’s a good egg. Eat yours, Albina: eat! I love a good egg.’

She nodded and copied his actions, picking off minute pieces of shell with her grubby fingers. He took a gulp of hot, sweet tea and smacked his lips.

‘Why do I love magic? Well, I don’t know. When I was a boy, growing up in Siberia, the people there… well, there were old traditions, and beliefs. Traditions that survived the Tsars, survived the Revolution, survived Stalin even… just. They will survive us all, I think. The native people there – I mean not Russians exactly, but the indigenous people, the native people who have lived there for thousands of years: the Yakuts, the Samoyeds—’ He broke off. Albina looked confused. ‘Native peoples, like Eskimos. Anyway, where we lived, it was mainly Russians who’d lived there maybe twenty, maybe thirty years. But somehow, the stories of the native peoples, who had lived there thousands of years, had soaked into the soil, the trees, the houses. You could see it and hear it, little snippets. Especially the children: we liked to believe in magic, in spirits, special powers, special people who could talk with the spirits, cast spells, see off evil and… and all that kind of thing.’ He stopped and cleared his throat. ‘Of course, it wasn’t encouraged. Our parents, the school teachers, the Komsomol: they told us it was all nonsense, told us the old beliefs were a result of the peasants’ struggle for meaning under the yoke of feudal and then bourgeois capitalist regimes…’

‘But was the magic real?’ asked Albina, spitting egg into his tea.

‘Well, of course the magic was real! If you sense it, it is so. If you see it and feel it, you can judge it for yourself. The wonder… mystery. It is very powerful, especially for children. Sometimes too powerful.’ He broke off and got up to throw the broken egg shells onto the compost heap. ‘It all came back when I was working in the bank. It was like… the other side of the coin. I had to be very serious and straightforward at work. Bank work does not give much opportunity for the imagination, or creativity, or surprise. So I liked to study something that brought me… life, a little: it gave me the magical power to make things appear and disappear. I liked to entertain, to make people think, and to doubt… but I just do tricks. For hundreds, thousands of years, Albina, people have needed to believe in magic, in a power… outside themselves. And that fascinates me.’ He shrugged, sighed, took a gulp of tea. ‘It’s much more interesting than money. Money hasn’t been around long, compared to magic.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу