‘It’s a good investment! And it’s sweet!’

Valya sprayed a film of tea across her friend as she choked. ‘Sweet? Polly? ’

‘At least they’re something solid in your hand, a real piece of Russian heritage! Not like those, what do they call them – shares? I mean, what are shares? Just worthless paper!’ Alla pushed the remains of her cabbage away. ‘Did you hear, the whole of School No. 4 was invested in PPP?’

‘The pyramid scheme? You’re joking?’

‘The headmaster thought he could triple the budget if he invested… they found his body washed up in the creek last Friday. He’d jumped off the bridge.’

‘Stupid man, God rest his soul.’ Valya rolled her tiny eyes as far as they would roll, and blotted her brow with a crinkly serviette. ‘Maybe Vlad could come too. I’d feel safer with him there.’

‘Safer?’

At the counter a broad woman in a stained white overall and a chef’s hat began shouting at the customers while brandishing a slotted spoon.

‘Time to go?’ asked Alla.

‘Time to go,’ nodded Valya. ‘Cook’s been at the home-brew. I’ll see you on Friday… if you live that long.’

She laughed deep in her chest and knocked Alla on the back with her fist. Alla coughed, and did not laugh.

‘I’ll phone Polly.’

‘Please do. Try to peel her away from my poor Vlad’s side. She’s a bad influence on him, you know. I can see the difference already. And it’s not good.’ She dragged her heavy autumn coat over arms bursting with flesh. ‘Ooh, that’s tight!’

‘A girl always spoils a man, that’s what I say.’

‘Well Alla, that’s a stupid thing to say. I didn’t spoil my husband: I improved him.’

‘Improved him into the grave.’

‘Now then! I didn’t know he had a weak heart. But Vlad… he was such a sweet boy. I know he’s not been with me long, but he was so attentive, so chatty. And now – he’s always on the phone, hardly eats a thing, constantly coming and going. And getting through so many pairs of underpants! He’s got huge bags under his eyes, you know.’

‘He’s young, Valya. Maybe you should have a motherly word?’ Alla smiled as she pulled on her gloves.

‘Motherly? I hardly think so!’ Valya’s cheeks flushed deep vermilion as she fanned herself by the open door.

Alla applied her bobble hat. ‘Then maybe we should ask Madame Zoya, you know, to ask the spirits… The departed often have a point of view, don’t they? They can tell if a romance is going right.’

‘Romance? It’s lust – that’s what it is! Come along, Alla. The poor boy’s being led by his—’

The door slammed on the words as the two ladies stepped into the street. Alla trotted quickly towards the bus stop, eager to get home and issue her invite, pleased at the prospect of discussing her digestion with a more qualified ear than Valya’s.

Valya herself waddled a few steps behind, the bright blue headscarf clinging tightly to her orange hair. She thought back to her days in the bank up in Rostov, and the curmudgeonly boss who had, just the once, taken a boiled egg from his lunch box and made it disappear. He’d shaken off their amazement, turned his back on calls for more. He’d been such a closed man, firmly sealed in his shell. Maybe now he was opening up? And who knew what pearls might lie within this old clam. She smacked her lips in anticipation.

Gor realised it was a Tuesday when the day was half-way through. He’d been caught up by Mussorgsky roaring from the record player. Mussorgsky always stirred his soul; both a pleasure, and a pain. This Tuesday, bright but with a chill, it was regret that bubbled to the surface as he tried to remember a trick, the ‘Sands of the Nile’.

The trick was a good one, when it worked. He would reach into a giant bowl of murky, swirling water and, with a grand flourish, extract perfectly dry piles of brightly coloured sand. Children always loved it. He remembered, suddenly, how Olga used to dangle her fingers in the bowl as he practised. He couldn’t believe he’d forgotten how to do it.

After she’d gone, he’d still been full of himself, forty-five years old and intent on success. Business had boomed, and he’d grown fat and busy, obsessed with his creature comforts. He’d guzzled the fruit of the orchard and sat back in his chair, enjoying the view of autumn days stretching ahead, content in the knowledge that he’d stored up for the leaner times and had it all bottled and pickled, everything he needed, at the back of the cupboard. But he’d forgotten his soul. And as he’d sat feeling smug, the material possessions he’d stored up so carefully were silently eaten away, as if by mice. Only then did he realise you couldn’t bottle happiness, you couldn’t pickle love. Now here he was, scavenging on the dust pile, seeking out scraps – and this time, all alone.

Old age had him by the scruff: he could barely walk without coughing, the legs were going too. The middle years, so important, so busy, had disappeared like so much melted snow, no more than a puddle on the mucky floor of his life. Where was the time? Where was the laughter? Where was his family, more to the point? Marina, his wife, Olga his daughter, even funny little Tolya? He had focused his energies on forecasts and fixed assets, budgets and bureaucracy. The wind buffeted the windows as he chewed his lip, pencil sleeping on the paper. How different life might have been, it whispered.

He looked up at the calendar: Tuesday 11th October. His mouth twitched, and he sprang from his chair. Rehearsal day! Sveta would be coming over. She would be limbering up at this very minute. The cabinet had to be readied, and a little bite of something prepared. He shushed Mussorgsky and headed to the bedroom to change. He would venture to the market. Tuesday was a good market day, as far as they went. And he would invest in some treats, in recognition of Sveta’s good comradeship.

As he stood wondering whether to opt for two sweaters, or one sweater and a jerkin, he heard a sound. It slipped into his ear: nothing much, just a tapping – fingers on glass, quiet, insistent. He held his breath and listened: it echoed around the empty flat. Hardly threatening, stealthily soft, but it squeezed his heart.

tap-tap-tap

It was the sound of loneliness, the sound of cold nights. The tick of the clock, the beat of the heart; the tap of time, marching onwards. Beads of sweat formed on his forehead. As if the intervening sixty years had not happened, he smelled pine needles and mud, machine oil and wood smoke. The wind whistled in the pines.

tap-tap-tap

He cried out, not a word, just a sound, a half-choked plea to no one. He knew that sound, it was familiar, like a half-remembered, recurring dream.

tap-tap-tap

Dasha, the queen cat, stepped silently through the door and four fluffy white kittens mewed their hellos. The spell was broken. Gor gulped in air and flung the wardrobe shut, cursing himself for a fool and stamping into his boots. How could he be scared of a little tapping! Where was his logic? Had his brain turned to fluff? There was no such thing as the supernatural! There were no such things as ghosts!

The kittens watched him, blue eyes wide, pretending to be brave with their backs arched and paws prancing. He apologised for the noise, smoothed down his wiry hair, and slammed out of the flat.

He found he needed some company, and the streets would serve very well.

Azov’s market was a modern structure: solid and unfussy on the outside, warm, dark and smelly on the inside. Clear plastic panels in the high-pitched roof let light into the centre, but the edges were folded in shadows: it was best to visit during sunshine if you wanted to see what you were buying, and how much change you got. The scent of overripe fruit swung sweetly, heavy in the air. Glowing persimmons and fiery pomegranates lay in pyramids side-by-side with precious local honey and bags of winter grain, while on the floor sacks of potatoes and turnips lounged in lumpen splendour. Gor ploughed along the narrow aisle, blind to the rough-skinned stallholders as they called to him, thrusting out samples, flashing gold teeth and knife-blades as they cut cubes of melon and blisters of pomegranate seeds. He needed no fruit.

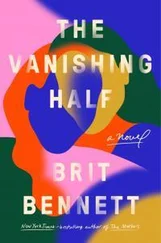

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу